- | 9:00 am

Is robotics set to upend the Middle East’s economies?

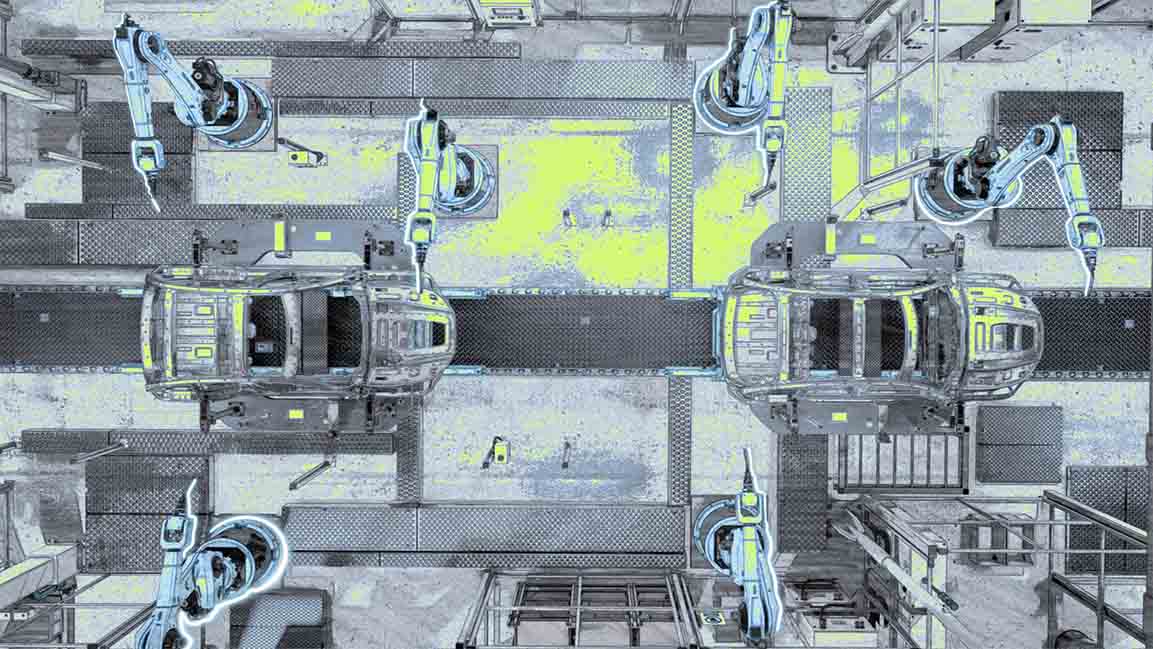

UAE and Saudi Arabia are investing in cutting-edge automation technology to increase productivity across several industries.

Robotics and Artificial Intelligence (AI) may be about to transform the whole world, but it is increasingly looking like the Middle East will experience the most seismic changes.

As part of its far-reaching goal of becoming a tech powerhouse, Saudi Arabia announced last month that it wants to triple the number of its factories to 36,000 by 2035. Up to 4,000 of these, such as the facility to make autonomous vehicles for the kingdom’s first electric car brand, Ceer, will encompass cutting-edge robotics and AI—a sector that, a PwC report says, could contribute more than $135.2 billion (or 12.4% of the country’s GDP) by 2030.

Days before the new Saudi National Industrial Strategy details emerged, Dubai launched its Robotics and Automation Program. The initiative aims to hasten the rollout of 200,000 robots over the next decade to increase productivity and efficiency across several industries, including logistics and precision manufacturing.

Five years ago, Dubai generated column inches worldwide with its smiley robot police officer, but away from its various customer-facing bots, the emirate has integrated AI into many key fields, from the surgical bots in hospital operating theaters to the drilling bots in engineering and construction. And then there’s cybersecurity, a sector growing so rapidly that Dubai has doubled down on its aim for robotics to account for 25% of all its law enforcement capabilities by 2030.

“Governments understand how robotics can significantly reduce costs in many sectors, from construction to agriculture to logistics, while using human labor more effectively,” says Ahmed Baharoon, an AI consultant and co-founder of Riyadh startup Inc Robotics. “However, many private companies are just starting to discover the savings and efficiencies robots can bring to their workplace and supply chains. Society will look very different in a few years here.”

This, Baharoon acknowledges, is part of manufacturing’s big global reboot. According to figures published by the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), the number of industrial robots worldwide has hit a new record of about 3.5 million, which represents a growth rate of 31% year-on-year and exceeds the pre-pandemic record of robot installation in 2018 by 22%.

Yet the wealthy Gulf States have particular incentives to create sustainable AI-leveraged economies at a breakneck speed.

Saudi Arabia’s enthusiasm for robotics and AI may appear to be focused on the 200 smart cities, such as NEOM, but climate change has already made the region too hot for humans to carry out crucial jobs in energy, construction, and agriculture.

Last month, Riyadh-based FII Institute—run by the Public Investment Fund (PIF)— bought a stake in Dogtooth Technologies, a UK startup that develops fruit-picking bots, helping to reduce crop wastage and cut CO2 emissions from fruit production. In Israel, FFRobotics has launched a bot that emulates human-hand picking for fruit harvesting. Another Israeli firm, Tevel Aerobotics Technologies, is fine-tuning a flying harvester.

Baharoon believes that autonomous robots will be involved in the planting of 50 billion trees across the Middle East, a scheme intended to help reduce global carbon levels by 2.5%. This is the equivalent of every person in the world planting six-and-a-half trees. “Happily, robots are more versatile than humans,” says Baharoon. “We have the technology to turn any vehicle, an excavator, for example, into a driverless machine capable of planting hundreds of trees an hour.”

But the climate is not the only pressing issue. Saudi Arabia, like the UAE, sees the AI revolution as a way of creating future-proof jobs, particularly in the growing private sector, for its increasingly well-educated citizens—two-thirds of whom are under 30.

Last year the Saudi rulers unveiled ambitious programs worth $1.2 billion to improve the digital skills of 100,000 young people by 2030, focusing on cybersecurity, programming, AI, and gaming. They also launched an additional $1.4 billion fund to promote entrepreneurship and support digital content.

A skilled workforce developing and supervising robots would also obviate the need for imported labor, Baharoon notes, which is a long-term strategy across several Gulf states. One-third of Saudi Arabia’s 33.4 million inhabitants are foreigners.

“In Europe and Asia, companies seek robotic solutions because of a labor shortage. There is no shortage of foreign workers here, but it is now too expensive for many companies to hire them,” says Baharoon. “However, if you want to make certain sectors more attractive for Saudis, robotics can help. It is no coincidence that PIF has invested so heavily in both robotics and the gaming industry.”

Inc Robotics will start manufacturing its custom robots in Riyadh in the next few months—a range of machines for the logistics, mobility, and cleaning sectors. “The benefit of local production is not only that it leads to a highly skilled domestic workforce,” says Baharoon. “It will also greatly improve the supply chain and result in a real hub of excellence in the region.”

Six years after PIF and Japan’s SoftBank created an investment vehicle for tech startups—from Uber to Jaka Robotics—around 40 companies are about to set up shop in the kingdom. These include Californian electric vehicle maker Lucid Group—61%-owned by PIF—which is building its first overseas plant in Saudi Arabia, from where it plans to make 155,000 vehicles a year from 2026.

At the same time, the Saudis claim that Ceer—a joint venture between PIF and the Taiwanese contract manufacturer Foxconn—will attract more than $150 million of FDI and create up to 30,000 direct and indirect jobs. According to Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman bin Abdulaziz, prime minister and chairman of PIF, the Saudi brand is projected to directly contribute $8 billion to the country’s GDP by 2034.

Moreover, the buzz at the Global AI Summit held in Riyadh in September was that the kingdom wants 400 more AI startups to stimulate foreign investments over the next two years.

By then, according to the PwC report, the Middle East could be attracting as much as $125 billion worth of investments in robotics, much of that likely to be skewed towards manufacturing technology hardware.

The groundwork that the UAE and Saudi Arabia have already laid as they push towards automation suggests that the evolution of the countries’ industries could be rapid, says the IFR’s Carsten Heer.

“There are no Middle Eastern or African countries on the global list of countries with a significant number of robots working in factories, but you only have to look at places such as Thailand and parts of Europe that have recently made that leap,” says Heer. “The Czech Republic came from virtually nowhere to be ranked 18th position worldwide this year, because Germany’s Volkswagen Group has invested huge sums in electric car and battery assembly plants there”.

Heer agrees with Baharoon—and with the claims made by Saudi and UAE leaders—that more industrial and service robots would lead to the creation of higher-grade jobs for humans.

“We have seen this happen in every country, including the US and China,” he says. “You need people to train and work with the robots, which are ‘cobots’.”

“While these machines can transform whole societies, they are still only machines. They can’t work by themselves,” adds Heer.