- | 8:00 am

Buying furniture online is a terrible experience. So, why are we still doing it?

Purchasing furniture sight unseen has conditioned us to lower our expectations.

Raise your hand if you’ve ever bought a couch online. Now, raise the other hand if the couch you ended up assembling in your living room wasn’t really the couch you had imagined you’d be assembling in your living room, but you kept it anyway, because you worked so damn hard to find The One. Are you really going to disassemble it, return it, and start from scratch?

Online shopping is convenient, and a true utility for people who don’t have easy access to brick-and-mortar shops. But when it comes to buying furniture, it’s also exhausting and, frankly, impractical. And for the thousands of direct-to-consumer brands relying on e-commerce for their business, it’s the perfect crime. They get to sell you *insert pejorative of your choice* furniture that looks stellar in 2D, but doesn’t always live up to your expectations in 3D. Leaving it up to you, the consumer, to decide if you want to compromise on your standards and just live with it, or embark on a “easy return” frenzy that is anything but easy.

As we find ourselves in another season of sales-inspired buying, it’s finally time to ask: Why are we so okay with buying furniture sight unseen?

E-commerce had already been on a steady rise for decades when the pandemic lockdown made it spike by 43% in 2020. The pandemic was a boon for the furniture market: The more time we spent at home, the more things we bought for our home, fueling a market that’s expected to reach just under $300 billion by 2027. I’m guilty of this myself.

Earlier this month, I spent weeks scouring the web for a quartet of dining chairs that are comfortable, sustainably made, and not $1,000 a piece. Then an ad for Levity popped up on my Instagram. The chairs looked padded for comfort, they were made of hardwood, and as a bonus, the upholstery was interchangeable. I was sold. When the chairs finally arrived over a month later (they were made to order), I was so relieved to be done with the hunt that I barely even questioned if I found them comfortable enough when I first sat on them. (I didn’t.)

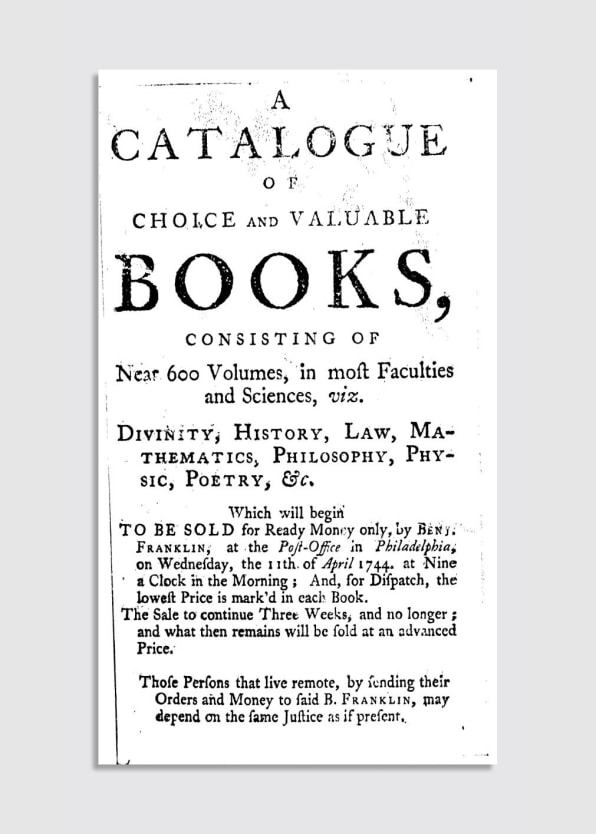

It is my personal belief that no one should be asked to shell out close to three figures on dining chairs without feeling them, touching them, or even sitting on them. And yet, this way of buying stuff has been the norm for well over a century. For most of history, people who needed things had to leave their houses to buy them. Then came Benjamin Franklin. Yes, the same Benjamin Franklin who invented the lightning rod also paved the way for the mail order business.

In 1744, the American inventor published a “Catalogue of Choice and Valuable Books, Consisting of Near 600 Volumes, in most Faculties and Sciences.” The verbosely titled tome was, in essence, one of the first shoppable catalogs, allowing people who couldn’t visit his shop to buy his books remotely. “Those Persons that live remote, by sending their Orders and Money to said B. Franklin, may depend on the same Justice as if present,” Franklin wrote on the opening page.

Even in the 18th century, convenience was king and, following Franklin’s publication, mail order business exploded. Soon, companies were selling seeds, books, and clothes by catalog. In 1871, Montgomery Ward & Co opened the world’s first mail-order enterprise, selling clothing, furniture, and hardware through illustrated catalogs that grew ever more colorful as the years went by. By 1897, what had started as a single page had grown to a 1,000-page catalog, and Ward’s annual sales had skyrocketed to $7 million, undoubtedly fueled by its “satisfaction guaranteed or your money back” policy, which it instituted in 1875. Sears jumped on the bandwagon in the late 1890s, as did The Hartman Company, which filled about $13 million worth of furniture mail orders in the 1920s.

During this period, people would make purchases based on pictures, says Sylvain Senecal, a professor of marketing at HEC Montreal whose research focuses on web-based marketing and consumer neuroscience. Buying sight unseen was part and parcel of North American culture long before the internet. Then, he says, catalog retailers were one of the first to embrace e-commerce: “They could reach a lot more people.”

Today, there are 2.5 million online retailers in the U.S., and 84% of them sell physical goods versus online services. From the consumer’s perspective, this creates a mind-boggling amount of choice that can lead some people (like me) to week-long searches for the perfect dining chair and maybe even cause decision paralysis. According to a 2018 study, 42% of consumers said they abandoned a planned purchase because there was too much choice.

“Most people see the value of the internet as having more information, but the real value is processing that information to reach the goal you want,” says Senecal. And because most people don’t have the time or desire to spend hours “processing,” e-commerce has fueled an entire industry of third-party sites like Honest Brand Reviews, and product review websites like Wirecutter or Fast Company’s very own Recommender. It has also made buyer reviews an indispensable part of the online shopping experience.

Senecal’s team has spent years analyzing consumer patterns using eye tracking and other tools to understand how people browse and make decisions when shopping on a screen. He says that people often start with a large assortment of tabs, filter out by color and price range, then narrow down their search on a handful of products before they do a “deep dive” on each contender. This is where reviews come into play.

If ratings are really low, people immediately remove the product out of the equation. “But if it’s good enough, they drill down and read the reviews,” says Senecal. And if they read one negative review in a group of ten positive ones, the negative review will be the one that sticks because “it carries more weight.”

But here’s the pickle: The internet is teeming with fake positive reviews. According to a report from the World Economic Forum, fake online reviews duped people into spending a whopping $152 billion on products and services in 2021. Some companies hire review farms to boost their business, and others offer cash incentives in exchange for a review. Most consumers, of course, remain blissfully unaware of these shenanigans. “If it’s a retailer they trust, they’ll trust everything on the page,” says Senecal.

Beyond reviews, DTC brands have mastered the art of assuaging consumers’ fear of buying furniture sight unseen by using a panoply of other tools. Features like 360° viewing, augmented reality modes that let you see your prospective couch in your living room, detailed photography, comprehensive sizing charts, free fabric swatches sent by mail, and of course, easy returns.

These tools have enabled many brands to stick to an exclusively digital business model, but others, like Joybird, are increasingly embracing the physical world as yet another marketing tool. Four years after it launched online, the furniture startup opened its first store in Brooklyn, followed by six more showrooms in Los Angeles, New York, DC, Chicago, San Francisco, and Austin (with a seventh one in Manhattan opening later this year).

According to a 2017 report by KPMG, 56% of people who shop in stores said they do so because they want to see or touch the item first; 41% said they’re concerned the product looks different. Showrooms like those Joybird is investing in can ultimately spur more sales, but they are also an opportunity to showcase the brand’s furniture while letting customers “meet our products in real life,” the company’s general manager, Gerardo Ornelas, wrote via email.

Ornelas says that in-store retail sales have “continued to grow” in the last year, but most sales still occur through the brand’s website. To cater to those customers, the brand has designed swanky room visualizers and 3D space planning tools that let you play interior designer and recreate your exact living room to see how various Joybird items would look inside it. They also offer free design services as well as a virtual store that lets them “bring the showroom experience to our customers via video call or chat,” says Ornelas.

Before any of those features existed, Joybird mostly relied on a sight-unseen model that even had its own explainer page on the website. The company assured me that page no longer reflects their business model, but even so, it almost reads as a preemptive apology to its future customers, using phrases like “take the leap” and “reward outweighs risk.” Joybird’s efforts to demystify the virtual shopping experience are a big step forward, but it’s also, in part, an admission from a digital-first brand that the sight unseen furniture model may not be in the consumer’s best interest.

This is the reality across the entire industry, but “DTC models will try to persuade consumers that there’s no risk in trying out the product,” says Senecal. “Even if you make a bad choice, there’s a way to recuperate the bad choice.” Consumers are led to believe the easiest way to rectify a bad purchase is to simply return the product, which is what my partner and I eventually decided to do with those dining chairs.

Of course, returning a product invites its own saga. For starters, you have to deal with customer service, which with Levity was perfectly helpful and responsive, but that isn’t always the case. In our scenario, we had made the fatal error of throwing away the packaging for two out of the four chairs, leaving us with the still unresolved task of having to shlep to the nearest Fedex to buy a new box. We now have to disassemble the chairs and orchestrate a pick-up window, not to mention pay a return fee of $75 per box. (In this case, two chairs fit into one box.)

Here I should note that only 5 to 10% of purchases made in-store get returned, but experts estimate that number can jump to 40% for online purchases. That Levity is charging return fees then, isn’t all that surprising. U.S companies spend an estimated $50 billion on product returns every year. Charging a fee can help them absorb some of those costs, and in the case of fashion brands, dissuade wardrobing, which is what happens when you wear your new clothes, then return them to get your money back. And then there’s the environmental toll. Returns are harmful for the planet, not only because they increase the amount of miles a truck has to drive to deliver then pick-up your purchase, but also because some products, from mattresses to clothes, may actually end up in landfills.

I’m not naive enough to think that any of this will dissuade people who love shopping online to stop doing it. Or that online retailers will change their practices and start opening physical retail locations all over the U.S. But online shopping for furniture as it stands is problematic, irritating, and environmentally damaging—and painting it as the epitome of convenience is just a lie we tell ourselves.

So, back my initial question: Why do we accept all of the complications that come with buying furniture sight unseen? According to Senecal, the answer is a pretty daunting one: Because it’s “the next best option” to shopping in person. The fact of the matter is that online shopping is both a blessing and a curse. You have more choice than ever both, but you have to work that much harder to strike gold.

Everyone has a different definition of gold, but for Senecal, not everyone is willing to spend long enough panning for it. After more than a century of buying furniture sight unseen, we’ve been conditioned to lower our expectations. “When you can test a product in store, I think your aim is to be closer to 100% [satisfied],” says Senecal. “Online, maybe you lower the bar a little bit.”

So, lower the bar I did. The replacement chairs arrived last week, courtesy of Blu Dot this time. They’re lower-profile and decently comfortable. Would I have bought them after sitting on them at a store? Probably not. But they do look nice in my dining room, and there is no way in hell I’m dealing with another return. I suppose they will have to do.