- | 9:00 am

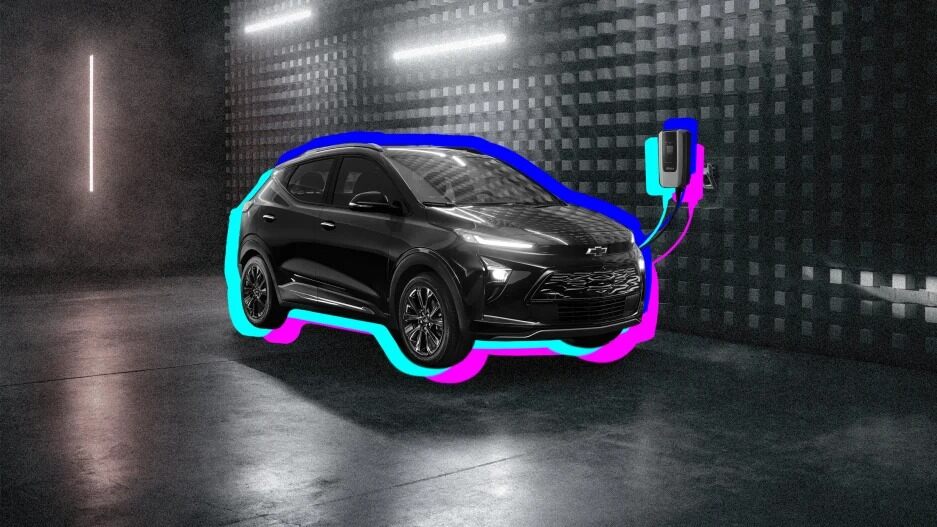

This Chevy EV is a bargain—and kinda drives itself

Chevrolet’s Bolt EUV is a nice, well-priced car that happens to run on a battery. And Super Cruise lets it do something remarkable that most costlier EVs still can’t.

The Chevrolet Bolt EUV electric car we were in had been doing most of the driving for almost 50 miles before my wife asked why my hands weren’t on the steering wheel.

We‘d set out from our home south of San Francisco to go antiquing in the Sacramento area—a 225-mile road trip I proposed to stress-test the Bolt EUV’s range on a battery charge. The excursion also gave me a chance to try Super Cruise, GM’s souped-up version of cruise control. Once I’d gotten us into a highway lane, the car steered, adjusted the speed, and braked on its own, while I supervised and intervened when necessary. The fact that my spouse didn’t immediately notice anything unusual going on was a sign it was doing a pretty competent job.

Regardless of whether the 2023 Bolt EUV was being steered by man (me) or machine (itself), it was my first experience behind the wheel of an electric vehicle at all. Borrowing one from Chevy for a few days seemed a good way to educate myself about EVs before I buy one, which I’m sure I’ll do once my 2014 Ford Focus is ready for the scrap heap.

The Bolt EUV, which debuted for the 2022 model year, is a slightly fancier sibling of Chevy’s Bolt EV, which has been around since 2016. It’s less SUV-like than the “EUV” moniker led me to expect, but it’s a very nice, comfortable hatchback with standard features such as the ability to brake automatically to avoid front-end collisions and hitting pedestrians. Moreover, it’s a deal: Even the loaded Premier Redline version I tried, with a sticker price of $37,885, is among the cheapest EVs you can buy. That’s before you account for tax incentives (which would currently add up to $9,500 in my case), the significant savings over time from kissing gas stations goodbye, and the bonus that Chevrolet covers the cost of having an at-home 240-volt charging outlet installed.

When I was doing all the driving myself, the Bolt EUV was pleasantly familiar. As an EV newbie, I kept forgetting that turning it on doesn’t summon the growl of an engine: It’s silently ready to go the moment you press the power button. (Putting it into drive, reverse, and park also involved pushing buttons rather than the traditional gear selector.) The car was viscerally peppier than my Focus, which takes its own time getting to 60mph and has been known to wheeze when going uphill.

Beyond showing me that driving an EV isn’t jarringly different from tooling around in a gas-powered car, trying this Chevy was a way to form an informed opinion about the dread syndrome known as range anxiety. If you can charge the Bolt EUV’s battery overnight at home, its 247-mile range should be plenty to get most people through most days. But what happens if you need to plug in when you’re out and about? I learned that there are four standards for charging plugs, no consistency at all to how much you’ll pay for electricity at a charging station, and wide variances in how long it might take to get your battery to 100%. Did I mention that there are multiple charging networks and that I ended up wanting the apps for three of them—ChargePoint, EVGo, and PlugShare—on my iPhone?

As I used public charging stations—which I did a lot, since as a non-EV owner, I don’t have a proper outlet at home—I had some mishaps. The very first charging station the Bolt EUV’s navigation system directed me to inexplicably wouldn’t let me charge up, even though it was part of the ChargePoint network. Another supposedly open station turned out to be behind a locked gate. At a couple of the EVGo locations I visited, I couldn’t get theoretically compatible power cords to seat properly in the Bolt EUV’s charging port.

Still, there were also moments when charging couldn’t have been much easier. More than once, as I turned into a lot where I was planning to park anyway, I found myself at an ultra-convenient charging station that cost little or nothing. Simply taking advantage of such opportunities would conquer much of my residual range anxiety. But for the record, when the Bolt EUV’s battery gauge showed that we’d be able to make it back from our Sacramento trip—but just barely—I spent 35 minutes charging at a supermarket just in case.

Okay, now back to that Super Cruise feature, which is a $2,200 option on the Bolt EUV’s ”Premier” trim level. It only works on highways, and only on 200,000-plus miles of roadway that GM has scanned, including almost all the Northern California freeways I tried. Unlike the version of the technology available on some much pricier GM vehicles, it can’t switch lanes. And you’ve still got to keep your eyes on the road, since it often switches off for one reason or another, with an alarm and flashing red light signifying that you need to take over. A sensor behind the steering wheel even keeps tabs to make sure your attention doesn’t wander.

This is nowhere near true autonomous driving. (Technically, it’s level 2 automation.) But if you’ve got a long highway commute and can plop yourself in one lane for most of it, Super Cruising might make one of the most tedious parts of your day quite a bit more pleasant. And if a reasonably cheap Chevy is already capable of taking its own wheel, I can’t wait to see what’s possible when I’m finally ready to buy an EV.