- | 8:00 am

Clip art changed the way we view ourselves—and the world

Clip art rose to ubiquity in the 1950s. Over the years, it became a mirror for the conversations happening in society.

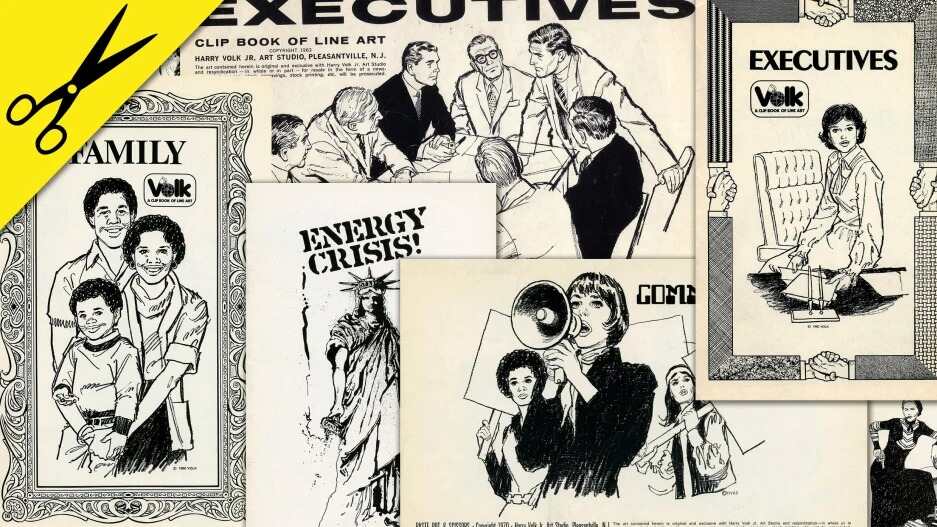

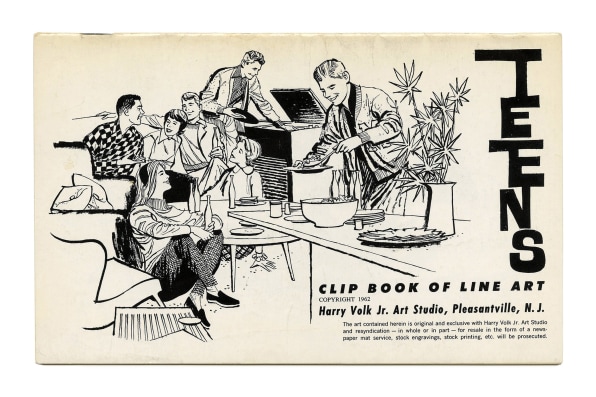

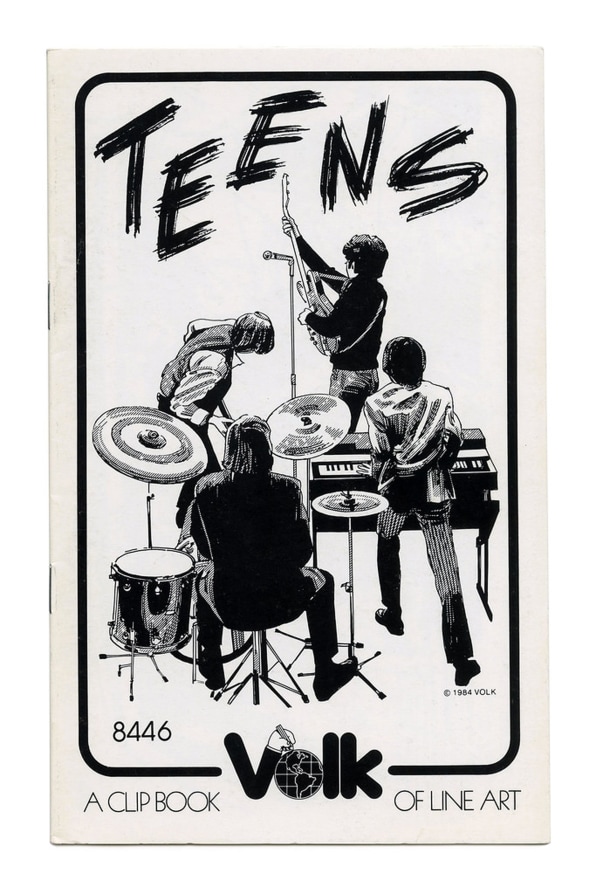

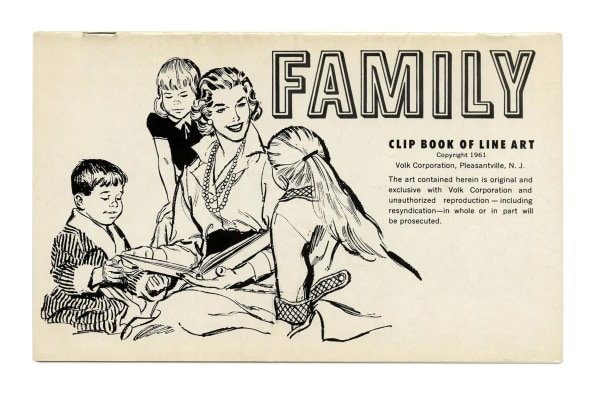

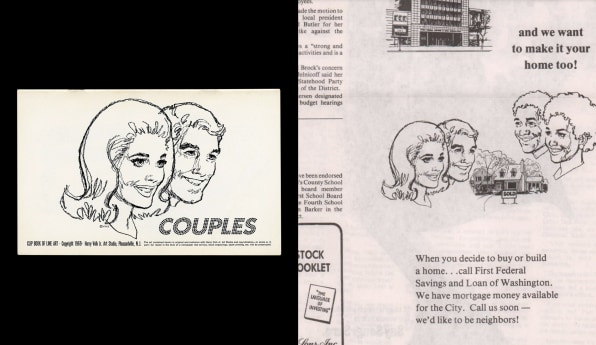

In the mid-1950s, Harry Volk Jr., a former journalist, decided to found a company that specialized in a burgeoning form of communication: the art of the nondescript. Over the next 30 years, The Harry Volk Jr. Art Studio, based out of Pleasantville, New Jersey, would offer staple-bound paper booklets full of copyright-free artwork organized thematically across a staggering range of topics, from Crime to Christmas, for just $1.75 to $2.50 per booklet.

These books of “clip art” (so named for the literal clipping and pasting required to place them in layouts in the time before desktop publishing) soon became ubiquitous in the art departments of advertising agencies, in-house organizations, and any other publishing endeavors lacking the budget for external illustration support. Their artwork was quickly found on advertisements, merchandise, and newspapers nationwide.

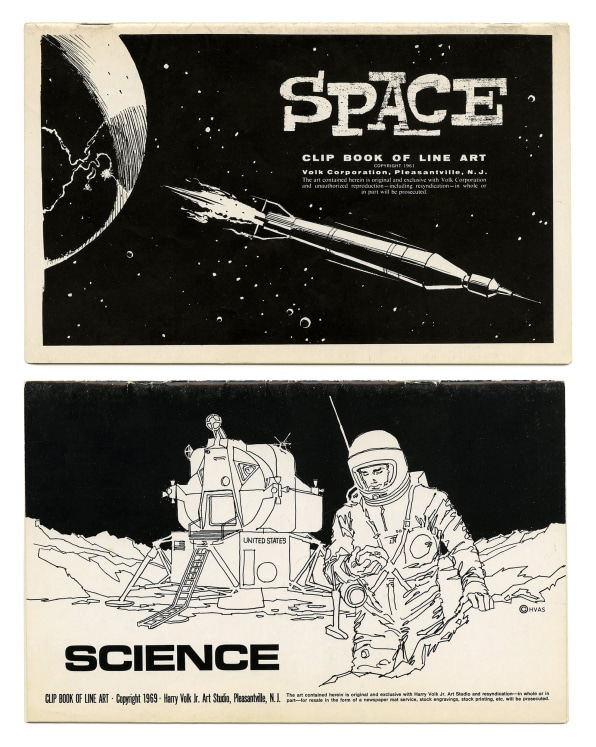

On a practical level, clip art has always served as a shortcut for those who lack artistic skills or the time to exercise them. But the artform’s significance goes well beyond convenience. In the mid-century, when Volk, and later other publishers like Dover Books, popularized clip art, it filled a market need for art that illustrated the cultural zeitgeist. Clip art was, in effect, a mirror for the conversations happening in society, as filtered through the illustrations that appeared in the press at any given time.

ONE COULD DISCERN WHAT WAS ON THE MINDS OF AMERICANS BY FLIPPING THROUGH A CLIP ART BOOKLET.

Editorial platforms and clip art creators became a sort of pendulum: As new subjects of interest emerged in the media, clip art distributors produced work to illustrate them, thereby defining the visual language associated with any given topic, and allowing the topic to be spread even further into the zeitgeist. One could discern what was on the minds of Americans by flipping through a clip art booklet.

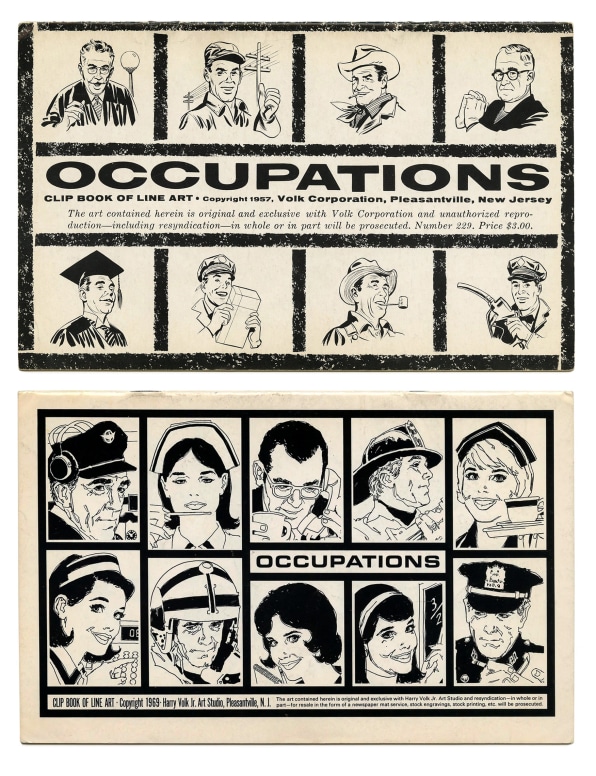

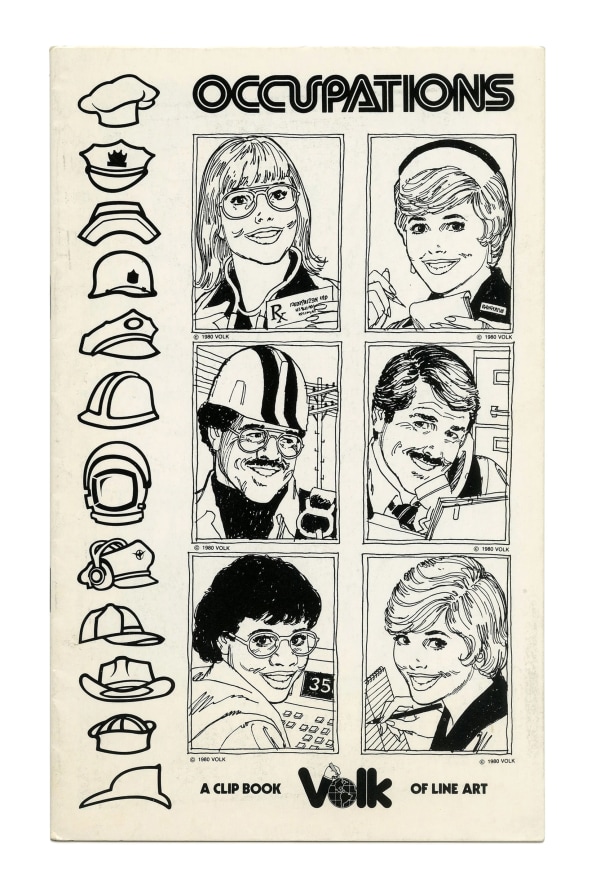

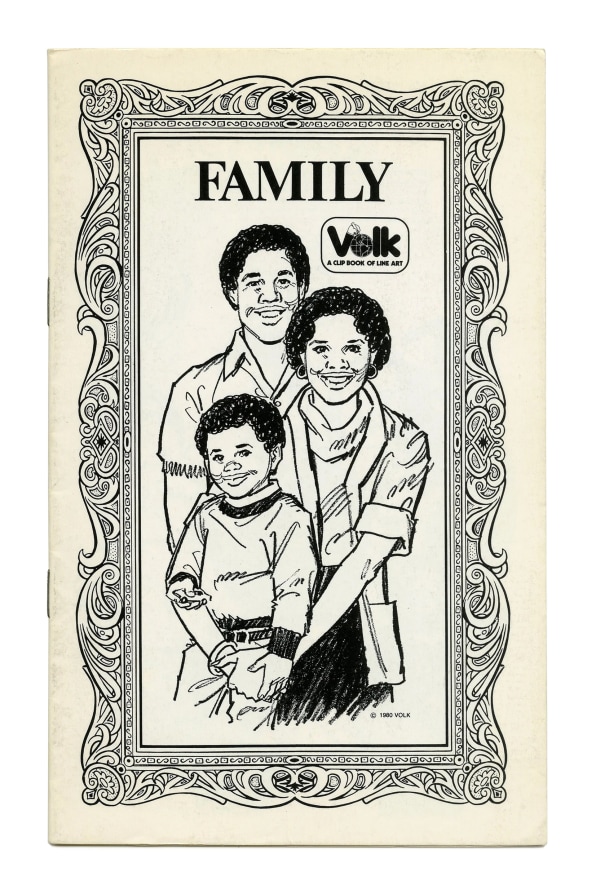

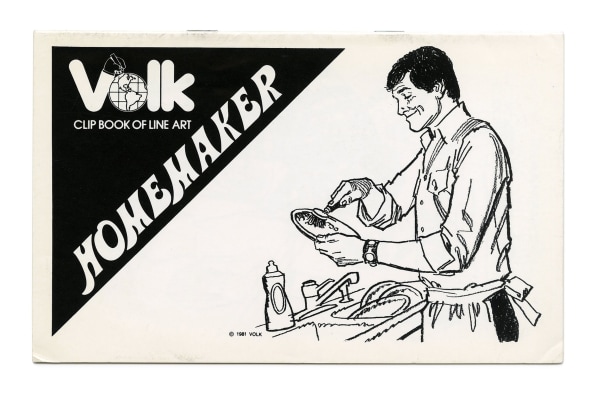

A series of Volk clip art booklets around the subject of occupations, for example, serves as a representative case study of changing societal attitudes around gender and race. The cover of the earliest Occupations booklet from 1957 is dominated by white men in stereotypically male-coded jobs like cowboy, farmer, and gas station attendant.

In 1969, the Occupations cover included a few women, though they were limited to service- and caregiving-oriented roles, including waitress, school teacher, and cashier. By 1972, the cover contained a single female scientist—a spot of progressive thinking amidst the sea of homemakers, secretaries, and bank tellers. Finally, in 1980, the first Black subjects appeared, as an electrician and a cashier, and white men are more appropriately represented—just one of six total subjects.

THE CASE FOR THE GENERIC

Clip art is undoubtedly a 20th century invention, steeped in the era’s massive rise of commercial interests in need of supportive artwork. But it can arguably trace its roots back to artistic compendiums of the late 19th century like Owen Jones’ 1856 Grammar of Ornament or George Ashdown Audsley’s 1882 The Ornamental Arts of Japan. These reference guides gathered a myriad of decorative elements and organized them into an index of sorts—decontextualized and simplified from their original use case in order to serve as thought starters for contemporary creators.

An index of aesthetic motifs planted the seeds for the idea of visual retrofitting, which today is commonplace in a world awash in content. Both an ornament dictionary and a manila folder of clip art allow people to find an existing open-source graphic to enhance their work. Both are pieces of visual imagery intended to be supplemental, easily mixed-and-matched for whatever needs arise. Clip art merely departs from its ancestors by moving from the ornamental to the representational. Rather than providing decontextualized aesthetics, it provides generic imagery to pair with a variety of possible contexts.

In that way, clip art also owes some of its DNA to the editorial cartoon, which is the symbiosis of text and image. The only difference is that with clip art, the user is left to fill in the text themselves (see also: The New Yorker’s back page). Stylistically, the aesthetics of early clip art and many editorial cartoons share an efficiency of mark-making. Some of this streamlining is by necessity, of course. Editorial cartoons tend to be done on a fast time line given their topical nature, but perhaps there’s more than pragmatism to it.

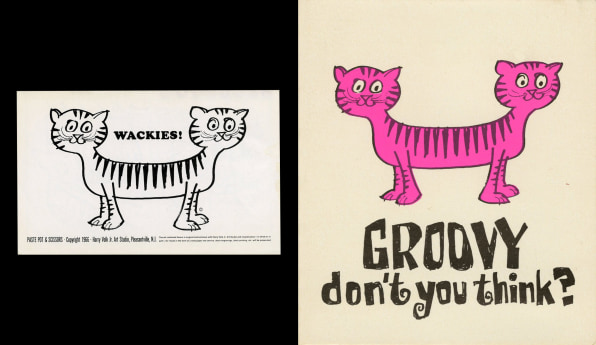

In his acclaimed book about the semiotics of cartooning, Understanding Comics, author Scott McCloud suggests that more simplified images allow for more universal representation and recognition. It follows then that clip art that’s too precise in content or execution would therefore be less functional for its users; some level of primitivism allows the artwork to be applicable to multiple situations at once.

This is certainly true of mid-century clip art, which, while ostensibly realist, hews closer to the more generic, cartoonish realism of Jack Kirby and Norman Rockwell (rather than the shaded realism of their contemporary Edward Hopper). It’s also true for clip art produced near the turn of the millennium, though perhaps more unintentionally, as their reliance on remedial computer graphics and early 3D rendering often resulted in imagery that relied on crudely shaded and strangely regimented geometric forms.

As an art form, clip art uniquely walks a tightrope between the need for simplicity and specificity. It’s an exercise in balancing broad appeal and contextual accuracy; the banal and the nuanced. It’s a well-worn visual shorthand that nods to a universally understood idea, while allowing for a wide range of interpretations and applications. This creates a unique dynamic where clip art simultaneously reflects and reinforces societal archetypes: The meeting point between the universal and the specific is the cliche.

THE LEGACY OF CLIP ART

While commercial clip art was born in the 1950s and ‘60s, it was still a trade secret, mostly utilized by marketing and publishing houses. (It should be noted that most of what we know about Volk today comes via the collection of creative director Bart Solenthaler, who rescued a large collection of Volk’s work from a trash heap at the New York Times.) By the 1970s, clip art was making its way beyond advertising agencies and into the hands of consumers, led in no small part by the publishing group Dover Books.

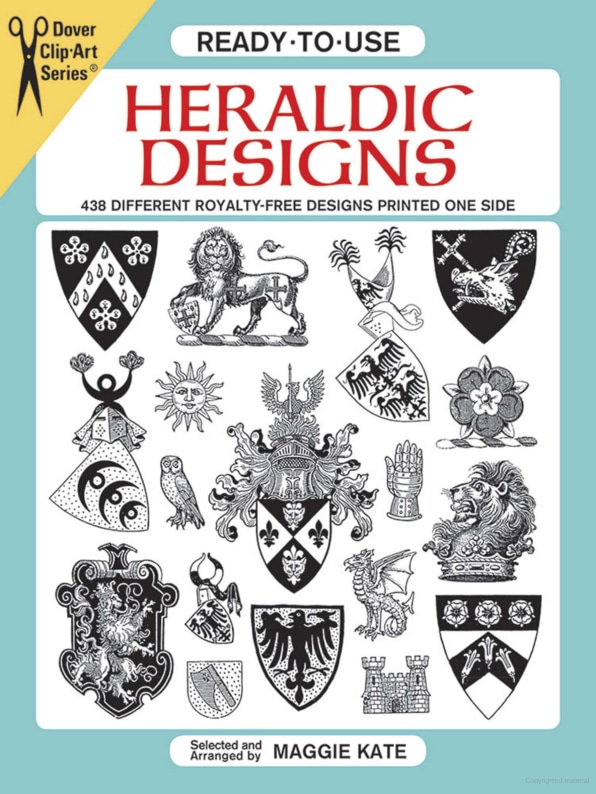

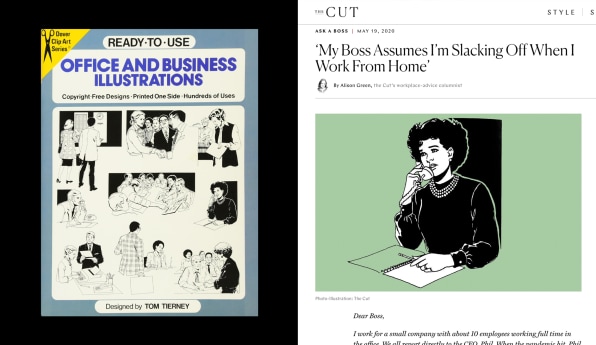

Founded in 1941, Dover built its reputation by “rescuing” classic texts from the public domain and reissuing them. The company played a significant role in revolutionizing the trade paperback market in the 1950s through its standardized editions. They did the same for clip art: reorganizing it by theme and packaging it in paperback booklets alongside an up-and-coming technology like the CD-rom. By the 1990s, clip art was no longer a niche back-of-house publishing tool; it was an art form any individual could take advantage of, thanks to desktop publishing.

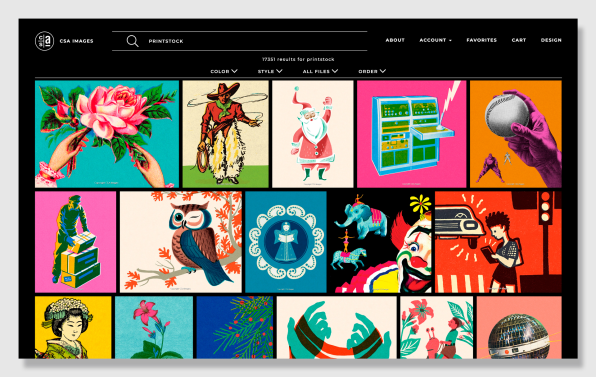

Today, clip art is more or less obsolete. In many ways, the internet marked the end of the clip art era. Microsoft’s Clip Art service, a staple in countless school papers and office presentations from the mid-’90s, bid farewell in 2014 as the tech giant shifted toward a new image-sourcing strategy. Instead of relying on its in-house Clip Art database, previously offered in-app via a sidebar, Microsoft directed Office customers to its Bing search engine for images with appropriate Creative Commons licenses. Consumers, too, no longer relied on dedicated clip-art libraries for their imagery needs, preferring instead to source images (legally licensable or not) via Wikipedia or stock websites.

While clip art itself may be an outdated mode of expression, the visual stereotypes it traded in have become archetypes in modern communication, both as functional allegory and universal meme. The proliferation of particular, somewhat abstract visual concepts applied to particular scenarios remains—the person with a lightbulb above their head to represent an idea; the man climbing an arrow to express growth. We may even have clip art to thank for the idea of the GIF library or the reaction GIF, which are scenarios retrofitted to an emotion, adding color and recognition to an otherwise banal observation.

Much of the copyright-free and pay-per-use illustration that users encounter today on the internet via stock websites (even more niche “retro” stock sites like CSA images, which purport to trade in more bespoke illustration) are simply reissues of Volk artwork, or Dover reissues from the ’70s, themselves re-editions of the illustrated detritus from the long past. The same material is chewed up and spit out again, only this time it’s watermarked.

The ultimate significance of clip art, and its long shadow, lies in its ability to democratize the process of creating visual graphics. Prior to the availability of clip art, creating imagery was largely the domain of professional artists and designers. Cut to the present day, and AI tools are replacing image search and stock, giving people the ability to create imagery without needing the skills to actually render artwork. But, like clip art, they trod in existing tropes and outsourced labor; compiled and pulled together from massive amounts of data or nonconsensual artwork scraping rather than via the output of a single individual. But what’s lost when even the generic is mass produced? Are we destined to simply proliferate the visual culture that came before us? Maybe a flip through a Volk booklet will illustrate the answer.