- | 8:00 am

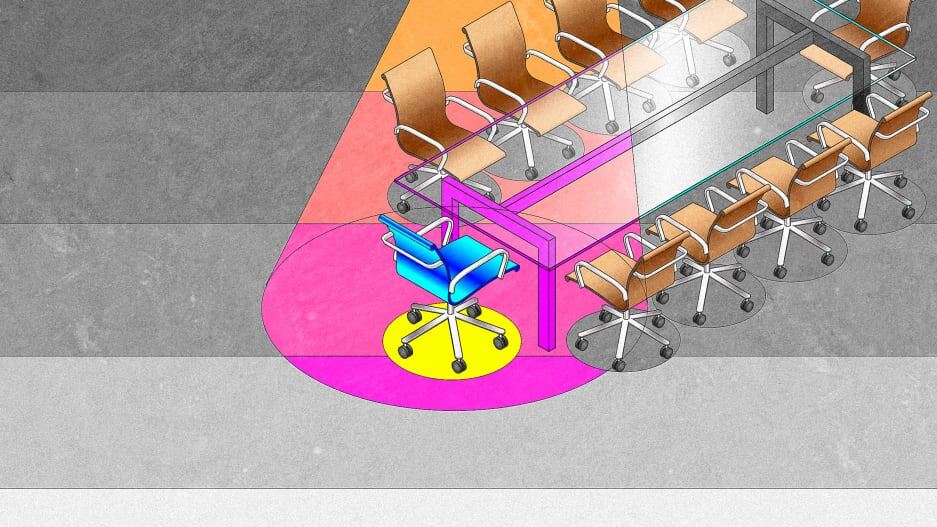

Designers have a seat at the table. Now what should they do with it?

Amid layoffs, burnout, and the rise of AI, designers are questioning how to build a more inclusive and sustainable future for themselves and each other.

In recent weeks, nearly every conversation I’ve had with a design and tech professional has culminated in some version of the same question: Is the industry reaching a breaking point?

Amid hundreds of thousands of layoffs, years of burnout and disillusionment, and the ever-increasing role of AI in our work, the future of the industry stands on shaky ground. These existential worries can ignite fear and numbness. But if we decided to, we could let this moment serve as an opportunity to reform our approach in the months ahead, with a greater focus on ethical innovation, communal care, and boundary-setting.

Whether this change will happen will depend on our ability to shift our attention, both as individuals and as organizations. I think about a recent conversation I had with Vivianne Castillo, founder of HmntyCntrd, who told me about the need to change focus, particularly within design, “from striving for relevancy to striving for maturity.” I wanted to investigate this concept of maturity further: What does it mean to strive for maturity in our work, especially amid escalating performance pressures, fears of irrelevancy, and the rise of AI?

As a designer who has worked and led teams across multiple industries and contexts over the past decade, I’ve seen—and have participated in—the game of striving for relevancy in the workplace. Often known as claiming “a seat at the table” in major business and product decisions, this approach has driven many companies, over the course of time, to consider design, research, and writing as critical roles within an organization.

But striving for relevancy has its faults, too. I have seen and heard how it can perpetuate environments where competition and self-promotion become dominant cultural forces, making innovation more vulnerable to stagnation, and ultimately distracting us from the real-world impact of our work.

While relevancy relies on our pursuit of getting a seat at the table, maturity asks us to carefully consider the relationships within and beyond the table—the way we relate to problem-solving, to each other, and to ourselves. When aiming for relevancy, we ask: How do we get a seat? When aiming for maturity, we ask: What happens once we get that seat? Who do we become, and what do we sacrifice, in pursuit of it? And who still doesn’t have a seat but should? Considering these relationships, and our ability to evolve our focus as designers, is a part of what makes us uniquely human, with skills that AI can’t replace. But what does aiming for maturity look like in practice?

HOW WE SOLVE PROBLEMS

In the pursuit for relevancy, the design profession is well known for employing fast-moving, collaborative activities for inviting stakeholders into the process of design. The end goal is to bring multidisciplinary experts together to solve problems and allow design to sit at—and perhaps set—the table. Often, it involves Post-it notes of ideas pinned to physical and digital whiteboards, mostly based on our own lived experience and assumptions of the problem. In a recent piece for MIT Tech Review, writer and designer Rebecca Ackermann argues that this process, often called “design thinking,” rested on a key philosophy: “We are all creatives, design thinking promised, and we can solve any problem if we empathize hard enough.”

For years, my workplace performance as a designer was tied to how well I followed this philosophy, and I did, until I was asked to design for countries, cities, and cultures to which I had no expertise. Empathy—a key selling point for why design was relevant to a company’s goals, and a key piece of performance criteria for designers—became unmasked as an exclusive, truncated process riddled with inequity. I pushed back on the philosophy, seeking entry points to change it by giving the Post-it notes to people with local expertise and aiming to create long-term partnerships with them. But the workplace pressures to perform as the sole design expert, one who could quickly solve any problem, remained.

Before developing a new solution, we strive for maturity by asking questions like: Who have we listened to? What solutions already exist, or how are people repurposing this tool or service to fit their context? What are we at risk of disrupting here that shouldn’t be disrupted? We mature our conversations by making these questions known early in the process and building them into our workplace performance criteria. We release guilt, shame, and blame for mistakes, and instead focus our attention on expanding our knowledge, even in small ways, like reaching out to an external expert and inviting them to the table, long before a solution—or even the problem—is articulated.

I’ve seen designers create a more effective real-world impact when they form relationships with communities by offering support, funding, and partnership—from projects like connecting tree farmers to data tools and funders, to partnering with gender equity and safety activists to map out local pharmacies and hospitals that they trust for people in crisis. In a model that strives for maturity, designers are not incentivized to be sole experts; rather, they are encouraged to be advocates and connectors.

HOW WE THINK ABOUT LEADERSHIP

In a model that strives for relevancy, designers are conditioned to believe that focusing on self-promotion, competition, and increasing the number of followers or direct reports is how we become leaders. Power and influence within a company, field, or platform can quickly take hold of our attention. I feel disheartened when I hear designers say that they feel compelled to focus their attention on the number of people who viewed a report or prototype they created as a way to get visibility for a promotion and rise in the ranks.

In a model that strives for maturity, we become leaders when we prioritize communal care and collective abundance. We decenter ourselves, even when we’re not encouraged to, by increasing opportunities for everyone. Maturity demands that we not only acknowledge the positions of privilege we may have; we take it further by sharing opportunities within the workplace or promoting the perspectives of our colleagues, especially people from marginalized backgrounds. In recent months, I think about all the people I’ve seen on my social media feeds who are sharing resources, networks, and jobs amid ongoing layoffs. This is a signal, I hope, that we aren’t seeking opportunities only for ourselves but for others, too. But will we commit to prioritizing communal care even when there aren’t mass layoffs?

HOW WE SEE OURSELVES AS PEOPLE

Burnout. Boredom. Trauma. I am shocked by the number of conversations I have with design and tech professionals who are continuing to experience these scenarios, especially when many of us are relatively early in our careers. In our quest for relevance, we failed to consider the emotional and physical cost in doing this work: being tethered to screens for hours; the propensity to overwork; sleep deprivation when traveling or working across time zones; the recurring trauma of reorgs and layoffs; and the exposure to potential harm and danger, particularly when researching in the field. This puts the longevity of our practice—and our ability to be human-centered—at risk.

When we strive for maturity over relevancy, we view our resources, time, and energy differently. We reject self-care as a well-being trope, and instead accept it as an urgent, ethical practice. Because when we’re not taking care of ourselves, the people impacted by the work we create are at greater risk of receiving an experience that lacks care for them. When we strive for maturity, we unapologetically honor and communicate the time, space, and screen boundaries needed to maintain our health and focus, and we build these boundaries into our workplace policies and expectations.

These examples demonstrate how aiming for maturity over relevancy can be a path through our current challenges that leads us toward a more equitable and responsible industry. Maturity, at its root, is anchored in the understanding that what and how we create extends beyond ourselves. It demands more than a seat at the table but a long-term view of how that table is taking shape. What are we teaching the next generation, both in what we do and not do? In how we mature or not mature our practice? What will we decide to leave behind?