- | 10:30 am

This Gates-backed startup uses super hot bricks to run factories with zero emissions

The bricks are heated with clean energy to over 1,000 degrees Celsius. That heat can then be used in factories that make products like cement, food, plastic.

At a factory making biofuels in California’s Central Valley, the product is sustainable, but the refining process still runs on fossil fuels. Now, the factory just started testing new technology that can eliminate that carbon footprint and cut costs: a giant “heat battery” that stores renewable energy in bricks.

The startup that makes the heat battery, Rondo Energy, is trying to solve one of the biggest challenges as the world tries to decarbonize. (Rondo is on the 2023 list of Fast Company‘s Most Innovative Companies in energy and sustainability, and backed by Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures.) Factories making cement, food, plastic, and other commodities use high temperatures in their equipment, and can’t easily use solar or wind power to generate that heat because renewables aren’t always available. “They need continuous heat,” says John O’Donnell, Rondo’s founder and CEO. “You turn on a tomato paste factory or steel mill and you run it for the better part of a year before you shut it off for an overhaul.” Producing industrial heat generates around 10% of the CO2 emissions in the U.S., or around four times as much climate pollution as the airline industry.

While it’s possible to store renewable energy in lithium-ion batteries, those are expensive to purchase and install. Wind and solar power also can be used to make hydrogen to run factory equipment, but that’s also expensive, and not very efficient—turning electricity into hydrogen means getting about half as much energy as you put in. Rondo says that its approach, which is 98% efficient, is cheaper than the fossil energy that factories use today.

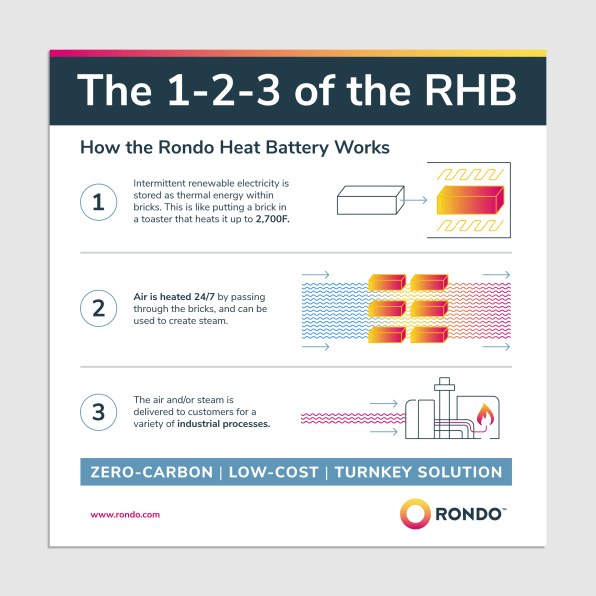

The heat batteries use the same clay brick material that some steel mills have used for 200 years to store waste heat, but with a new design. As electricity passes through a wire, the wire gets hot and heats up the bricks— the same basic process that a toaster uses to toast bread. The insulated brick material then holds the heat. “It’s almost embarrassingly simple,” says O’Donnell. The team developed a system that heats a set of hundreds or thousands of one-ton bricks uniformly to over 1,000 degrees Celsius (or 1,832 degrees Fahrenheit), and then delivers the heat on demand, by passing air through the bricks, as the factory needs it.

“Every day, you’re charging when the sun is up or when the wind is blowing,” he says. “And it’s long enough duration energy storage, 16 hours, 18 hours, so that it bridges the gap and gives you continuous energy from that intermittent supply.”

It’s hot enough to run almost every industrial process, with a couple of exceptions. Some steel furnaces use hotter temperatures and will likely need to use hydrogen power to eliminate emissions. Part of the process of making cement also needs to be hotter, though Rondo says it can cover the other two-thirds of the energy needed at cement plants. Overall, around 90% of industrial heat could be replaced by the technology.

Because Rondo’s tech can store excess renewable energy, that helps drive down the cost. Wind and solar power are already cheap, but at certain times—like the middle of the day in California, when there’s often more solar power generated than the grid needs—it’s even cheaper. Grid operators struggle to deal with the excess power and it’s sometimes wasted.

“Industrial heat, powered by these heat batteries, becomes a solution to these problems in the grid,” says O’Donnell. “And these problems in the grid, in turn, are sort of a solution to industrial heat because there’s a source of energy that was being thrown away that we can put to work.”

The installation at the California factory is a pilot, with a much smaller unit than factories will ultimately use, and is the company’s first commercial deployment. (It’s the first “electric thermal energy storage” system in the U.S., and the highest-temperature system of this kind in the world.) At the factory, right now, it’s still only covering a tiny fraction of the energy used. But the larger units can be manufactured quickly.

“If you can’t go to scale fast, among other things, you’re not climate relevant,” O’Donnell says. More than a million tons of the brick material is already in use today at factories storing waste heat; it’s already widely manufactured globally, along with the other parts of the system. In 15 years, the company aims to scale so broadly that it’s possible to eliminate 15% of global emissions.

Other potential ways to cut carbon at factories, like carbon-capture devices, add cost. But because Rondo’s tech is a cheaper source of energy than what factories use now, it could be quickly adopted. (The company sells heat as a service, rather than selling the equipment.) Energy is often 30% to 45% of a factory’s total cost of production. While carbon capture might make commodities more expensive, the heat batteries could make them cheaper. “There’s this decarbonized future where there’s more wealth, not less, and decarbonized steel or baby food costs less,” O’Donnell says.