- | 3:00 pm

Google spills the secrets of its design

At the biggest design fair in the world, the company demonstrates how nature shaped its products—and its maturity as a design company.

The perfect, stainless steel cylinders brim with water that shouldn’t be behaving as it is. It’s not still, nor is it gurgling or making waves. Instead, one tub ripples with the dimpled pattern of focaccia. Another strobes like a stop-motion movie. Yet another seems to tremble as it holds together a series of concentric rings, as if its muscles are about to give out and the water will slosh to the floor. (For the sake of my shoes, I’m relieved it doesn’t.)

This is Shaped by Water, a weeklong installation conceived and created by artist Lachlan Turczan, commissioned by Google and executed with some assistance from its hardware design team. Currently on display at Salone del Mobile—the largest design fair in the world, which takes place annually in Milan—Shaped by Water is a three-room sensorial delight for anyone who can attend. But it’s also a peek into Google’s design process for those who can’t.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF WATER

In a discussion leading up to the event, Google VP of Design Ivy Ross explained to me that water had become something of a metaphor for the design team during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the late Bruce Lee once articulated, water has the ability to change states from solid to liquid, to flow past any obstacle, to crash with ferocity, and to sit with stillness. And so it becomes a powerful personal model to emulate.

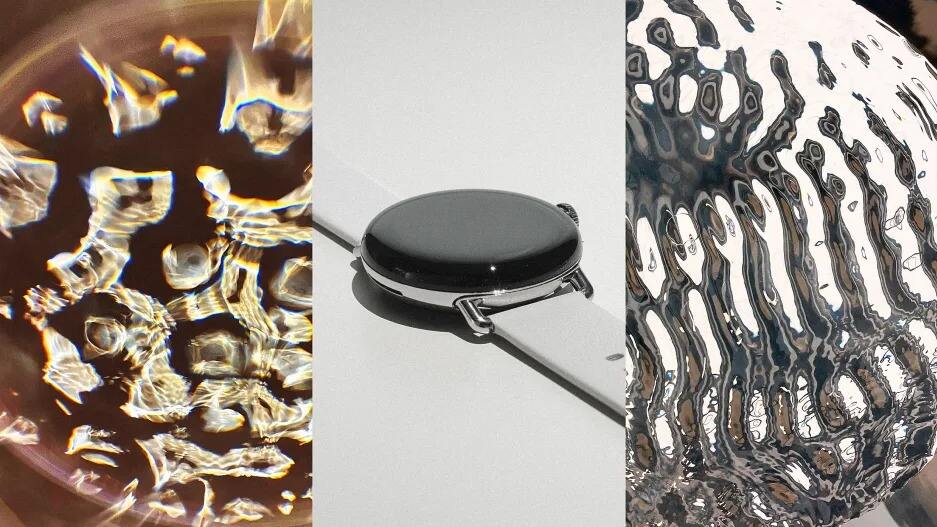

But Google’s designers didn’t stop with the metaphor. In the Google Design Lab, they were inspired by that thought, and they began experimenting, dropping water onto plastic and metal to see what sorts of shapes it made before its surface tension broke. Those experiments became part of their actual design process in 2020. And over time, some of those exact curvatures made their way to real products such as Google’s Pixel Watch and its Nest Wi-Fi Pro. (But more on that in a minute.)

When Ross was considering what Google might do for its second appearance in Milan, she was coming off of a well-received 2019 debut called A Space for Being. That project had visitors don sensor wristbands, then placed them in three differently decorated rooms. At the culmination of the experience, people could see their data to recognize which room made them the most calm or more alert.

What could have been a gimmick was a taste of cutting-edge science—proof that aesthetic experiences can measurably affect our physiology and improve mental health. It’s a phenomenon that Ross would later cowrite a book about alongside Susan Magsamen, executive director of the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, that became a bestseller when it debuted in March.

After her team was so taken by water, they decided that an idea around the shape of water would make for a good exhibition. Ross cold-called Turczan after seeing a bowl he’d created, which used the otherwise invisible waves of sound to coax water into unique formations. What followed was a dream commission that has consumed years of his life since, he says.

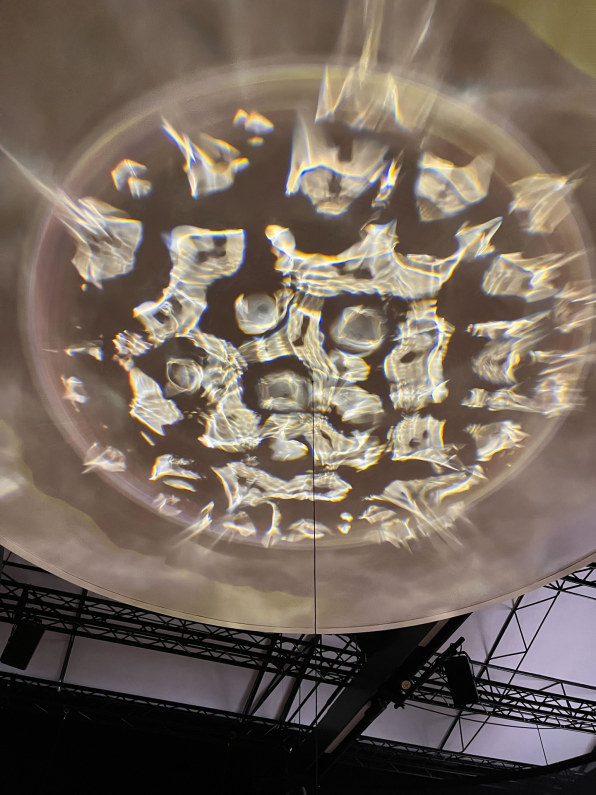

After walking through the first room of glimmering steel cylinders, you spiral your way through a large snail shell of mesh to arrive at a circle of seats that surround a small bowl of water. Here, Turczan projects light through the bowl, into a focusing lens, and onto the ceiling like a black-and-white art house film. (Google’s designers actually created the furniture in the exhibition. In this case, they needed a comfortable seating system so that 25 people could lie on their backs, side by side, with their feet on the floor.)

Over the next 10 minutes, water ripples to the music of Maurice Ravel and Nils Frahm, with the vibrations of the orchestration itself translating water into a seamless animated experience. I see crumbling ice and dancing crystals. Another person claims she saw an eye.

“Everyone sees something different,” Turczan says. “It’s like a flickering flame or staring at clouds.” In any case, I found that it forced me into a pleasant meditative state—one that will be familiar to anyone who has experimented with the natural trip of sensory deprivation or sound and light rooms.

“I personally think the art of the future is that we need to get out of our cognitive minds,” Ross says.

THE SHAPE OF WATER

Once you collect yourself, you head into the final room, which is where Google demonstrates how its own products relate to all of this water.

Approaching a display with the Pixel Watch, the link to water, at first, feels impossible to see. There’s a Pixel Watch on the left. And there’s a Pixel Watch, without its band, on the right. But then an assistant standing by takes a water dropper and releases a single drop onto the watch on the right. The drop sinks straight into the surface, and you realize it’s not a watch rendered in glass, but a watch rendered in water.

The design demonstrates the literality with which Google’s team was inspired by nature to create its design language. This Pixel-water doppelgänger is a real stomach drop moment—a reveal that feels too perfect to be real.

WHAT IT LEAVES YOU WITH

With Shaped by Water, Google created what has already been one of the most buzzed about projects at Salone de Mobile (it’s in every major guide to the event I’ve seen), and that was before anyone showed up to see it. The specific ROI—a certain prominence on the international stage of design—may feel tougher to swallow during a year when Google laid off a significant chunk of its UX designers (though it’s also worth noting this project was budgeted before that time).

But with design still proving to be a powerful differentiator in business, companies recognize a need to attend to be part of the creative mindshare. As Belen Frau, the global communications manager at Ikea, put it to me last week: “Milan is an incubator of ideas and innovation, it is like, you have to be in Milan.”

Consider that just six years ago Google didn’t even have a dedicated hardware studio, and while the company is not the most dominant player in its field, its design team has undeniably elevated the craft of forgettable techie products like Wi-fi routers into gorgeously formulated, mass-produced objects of desire. And I guess we have water to thank for that.

What I will be watching for in the future is not simply whether Google hardware remains compelling, but whether Google itself, or any major company, can distill more of Ross’s broader thesis into product. Namely, that the objects and experiences around us affect our psyches and physiologies in profound ways we are only beginning to understand.

This is a time that—a risk-averse Wall Street be damned—begs for ambitious experimentation beyond ChatGPT. Imagine what could happen if it weren’t just artists who got to play in this amorphous, sensorial world at events like Salone. Imagine what could be if designers were encouraged to explore how they made us feel—not just act.