- | 8:00 am

This startup just turned CO2 into yarn

Making fabric usually requires a lot of CO2. Using Rubi’s new yarn makes the process carbon negative.

The fashion industry has a massive carbon footprint, partly because of all the inputs required to produce fabric. But inside a lab in San Leandro, California, a startup uses enzymes to “eat” carbon emissions and turn them into cellulose, which it’s then using to make textiles that are carbon-negative.

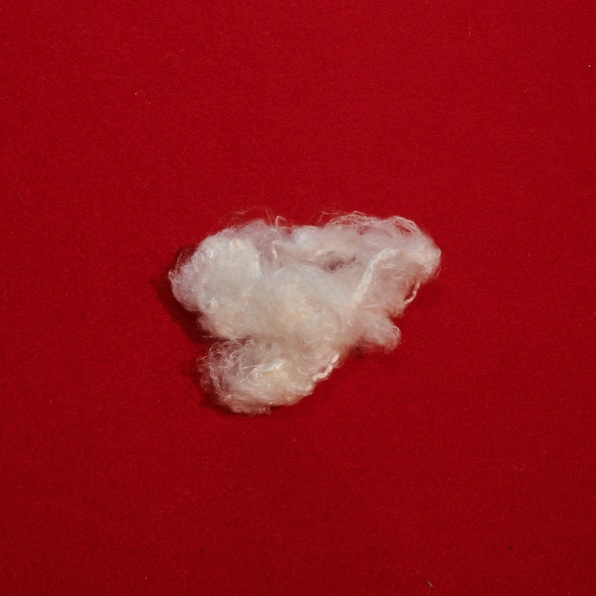

“Our process mimics how trees work: trees breathe in CO2 and use enzymes—proteins that help reactions happen—to convert the CO2 into strong carbon polymers in the trunk and leaves called cellulose,” says Neeka Mashouf, cofounder and CEO of the startup, called Rubi. Inside industrial reactors, the company does basically the same thing, creating cellulose polymers that can be spun into yarn.

The yarn can be made into lyocell, a fabric that’s usually made by dissolving wood or bamboo. “We make the same high-quality lyocell without the carbon-, water-, and land-intensive manufacturing methods that are based on deforestation and significant energy-intensive processing,” Mashouf says.

Typically, lyocell has a carbon footprint of 5 to 10 kilograms (or about 11 to 22 pounds) of CO2 equivalent for each kilogram of fabric, she says. The new process ultimately sequesters carbon instead, meaning that even when other factors are considered—like the energy that’s used to make and transport it—it goes beyond shrinking emissions to zero and has a positive benefit. The company’s cellulose can also be made into yarn for viscose or rayon, other fibers that are usually made from wood pulp.

Some other companies are also using carbon emissions to make fabric. Lanzatech, for example, uses fermentation to transform pollution from factories into the building blocks for polyester that have been used in capsule collections by companies like H&M and Lululemon, and foam used in a prototype of new sneakers. But Rubi argues that its own technology is more affordable and saves energy.

“Other technologies, like microbe fermentation and electrocatalysis, can be costly to scale, operationally complex, inefficient, and never achieve carbon-negative impact,” says Mashouf. Rubi is also creating cellulose, a natural, biodegradable material, rather than a synthetic fabric like polyester.

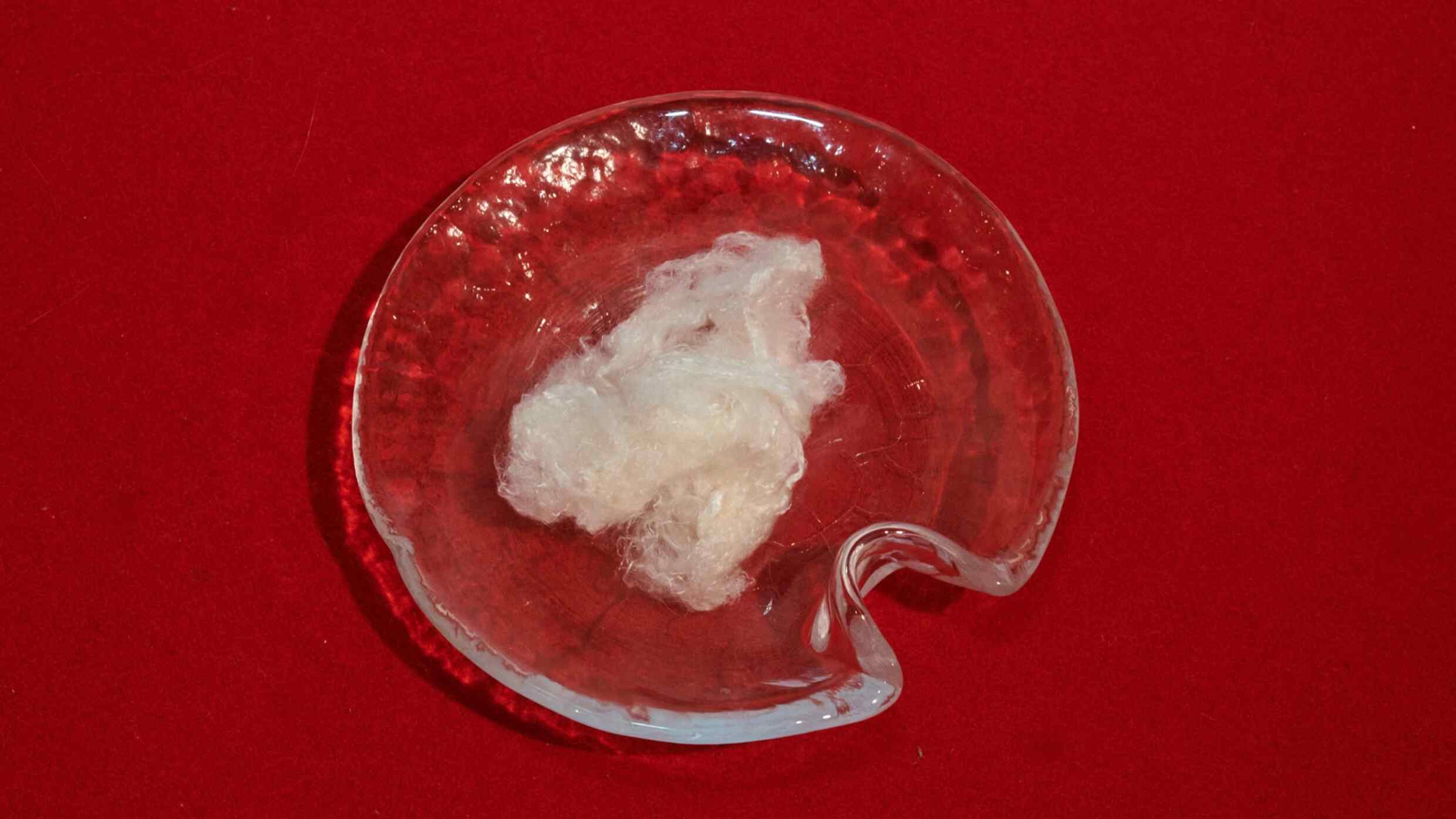

In Rubi’s Bay Area headquarters, the startup built a lab-scale manufacturing system for the yarn, using canisters of CO2 blended to mimic factory emissions. Soon, the company plans to begin working with factories to set up technology to capture and convert emissions on site. As the company scales up, the yarn will be made directly at existing textile production plants.

The first yarn samples perform like high-quality lyocell, Mashouf says. The company partnered with Ganni, a clothing brand based in Copenhagen, to pilot the new material. Ganni will use a fabric made from a blend of Rubi’s yarn and conventional cellulose to make clothing for its line. The partners just unveiled samples of the new yarn; fabric and garment testing will come next.

Rubi aims to help the whole industry transform. “The material manufacturing methods in apparel, and most other heavy industries, need to be completely reinvented to achieve any significant carbon targets,” says Mashouf.