- | 8:00 am

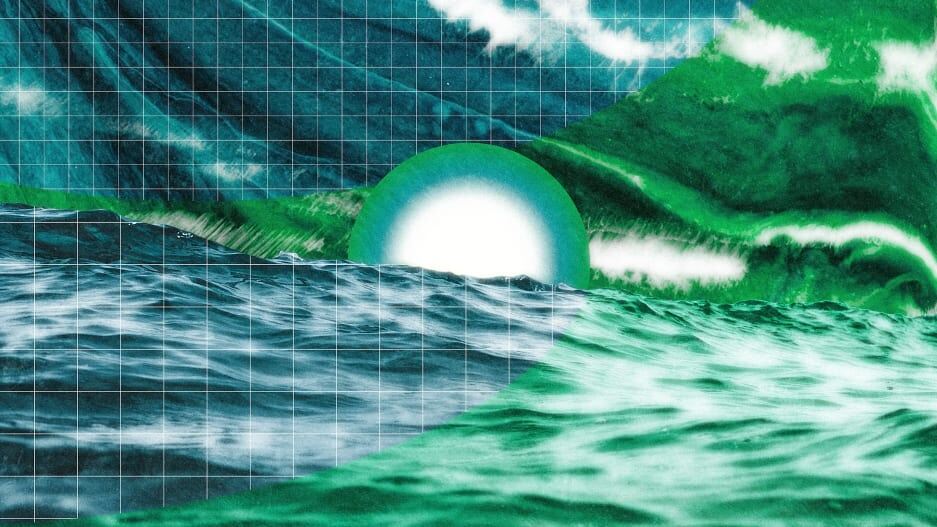

Climate change is altering the color of our oceans

A shift in color is more than an aesthetic problem—it’s a sign that the ocean’s ecosystems are becoming unbalanced.

People who live on the coast have likely come to notice very slight changes in the color of the ocean, season to season, and even day to day. But to the human eye, it’s hard to spot precise patterns—let alone decipher causes.

Now scientists have shown definitively, however, that the color of the majority of the world’s oceans has been changing significantly over the past two decades—and that it’s likely due to human-induced climate change. The color shifts matter in that they signal changes in ecosystem balance, which have the power to disrupt fragile marine food webs.

We may value the color of the ocean aesthetically, perhaps admiring a pretty, deep-blue sea as looking pristine and clean. But color is a sign of life and activity, or lack thereof—“a literal reflection of the organisms and materials in its waters,” write the authors of a new study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Generally, a bluer ocean means less life, especially at the surface, and greener waters means more activity.

Though a green hue can also be a sign of pollutants, it’s a big indicator of phytoplankton, tiny, plant-like microorganisms that contain green chlorophyll. They are at the bottom of the food web, providing sustenance for krill, small fish, and some crustaceans—but impact everything up to bigger fish, seabirds, and charismatic megafauna like polar bears. Too much, or too little, of these microalgae could be bad for the health of the entire ecosystem.

Color changes do happen organically, as weather patterns shift from day to day and season to season. For example, spring brings more light, with more energy for phytoplankton. Winds, like El Niño and La Niña, and storms also affect the abundance of these organisms. But the MIT researchers noticed changes that extended outside of this natural variability.

Using images from a satellite already in orbit, the research team looked at the changes in color over the past two decades, measuring different wavelengths with a light-measuring tool on the satellite. They noticed various color changes: Some areas, at certain times, became bluer, and others greener—and sometimes even closer to red. But the shifts were too subtle for the human eye. “These are changes that you really do need sensors to see, and you need long periods of time,” says Stephanie Dutkiewicz, a senior research scientist at MIT.

The changes linked up closely to what Dutkiewicz had been seeing virtually for years by running simulation models. These models, which she helped develop, allowed her to predict the future of the ocean color in two scenarios: one, with natural variability only, and the other, with greenhouse gases pumped into the atmosphere.

Researchers paired the satellite findings with Dutkiewicz’s virtual models, and the greenhouse gas scenario matched up almost identically to the real-world images. “I wasn’t surprised, because my models have been telling me this will be happening,” she says. “But it is definitely sobering to actually see it happening in the real world.”

The team found that the color changes were occurring in 56% of the world’s oceans, particularly in tropical regions nearer the equator. That doesn’t mean it’s not happening in the parts of the ocean closer to the poles—“it very likely is,” Dutkiewicz says—but it’s currently harder to distinguish the changes from natural variability in those areas.

Where the shifts are happening, it means the marine ecosystems are likely out of balance. There may be too much or too little phytoplankton—or bigger or smaller kinds—in certain places, and not in ideal quantities. Dutkiewicz uses an analogy: It’s like having too much rain in areas that aren’t used to rain, risking flooding; or too little in places that expect it, threatening drought. “It’s taken millions of years for our ecosystem to be in balance,” she says. “If you now suddenly perturb it, that’s going to have consequences. And many of them are not going to be good.”

Food web aside, the changes could also be affecting the carbon cycle, since phytoplankton are instrumental in allowing oceans to capture atmospheric carbon via their chlorophyll.

At the moment, the results can’t prescribe specific mitigation solutions; the scientists intend to continue their research to learn more precisely where, when, and how much phytoplankton levels are changing. “What it is,” Dutkiewicz says, “is another wake-up call for the fact that we’ve really changed our planet.”