- | 8:00 am

This NASA-backed robot is the droid coworker you’ve been dreaming of

Apptronik and Argodesign designed Apollo as an antidote to sci-fi tropes.

At 5 feet, 8 inches tall, and 160 pounds, Apollo 1 stands in a warehouse ready for the next shipment to arrive. Its eyes are fixed on the landing zone as it prepares to unload the boxes from a truck and move them into shelves and pallets. Its fully electrical human-shaped body—capable of lifting 55-pound boxes without flinching—is made of metal, plastic, some silver fabric, and metal actuators.

Apollo, clad in white, gray, and bright orange paintwork, features “tattoos” that identify the function of each of its parts. Its black chest reads Charlie—the humanoid’s name—set in sober, bright white sans serif typeface, along with simple icons that tell its current status. Its face remains blank until a human coworker passes by. A subtle smile illuminates its white face before disappearing a second later. The quick expression does its job of acknowledging the human’s presence without saying a word.

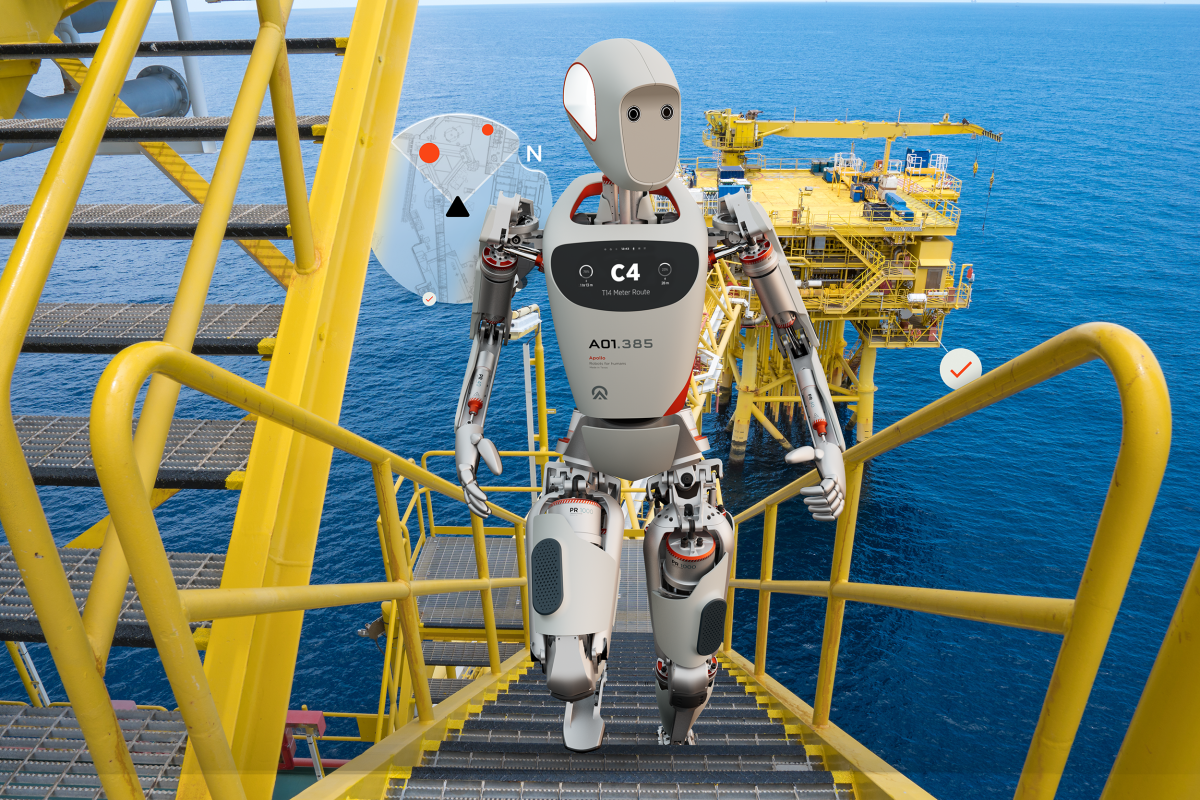

Apollo 1 is the first functional humanoid worker in history that can autonomously operate in a factory alongside its meatbag colleagues of today. It will not be washing your dishes or working at oil platforms just yet, but as you watch Apollo working, unloading boxes from a conveyor belt, its design just feels right, sort of like the iPhone felt when you held it in hand for the first time.

Made by robotics company Apptronik, Apollo is the distillation of years of humanoid development and the design work of Austin-based creative studio Argodesign. The NASA-backed robot is designed to perform warehouse tasks like lifting boxes and placing them on shelves. But unlike many of its droid-worker brethren, both its appearance and user experience goes against many of the preconceived notions of what a humanoid robot should be.

Apollo makes Elon Musk’s humanoid, Optimus, feel like a cheap cosplay automaton stolen from a bad Will Smith movie. It makes Boston Dynamics’s Atlas look like a terrifying giant. Unlike the latex-skinned uncanny valley freaks and all the cute R2-D2 wannabes out there, Apollo redefines many of the tropes that have characterized decades of robots in sci-fi literature, comic books, and Hollywood movies.

Apptronik and Argodesign wanted to establish a new relationship between robot and human, one that regular people—accustomed to the Terminators and C-3POs of Tinseltown—would not be expecting, but would find instantly familiar. The challenge with Apollo was to make a machine that feels humanistic without pretending to be human, Mark Rolston, founder and chief creative officer of Argodesign, tells me over a video call. “You know, all those science fiction presumptions don’t give you a guideline to backstop your thinking. We really had to come up with new answers.”

Rolston says from the start they knew Apollo had to be more than just a machine. “It had to convey emotions, intentions, and, above all, it had to be relatable,” he says. All that but without being overly cute. Argo drew inspiration from Apple’s minimalist aesthetic to the sleek lines of sport motorbikes. “The sport bike influence is evident in Apollo’s paint schemes and the beautifully crafted parts. It gives Apollo a sense of speed and agility,” Rolston says. To soften its appearance, they used a woven fabric to cover some of Apollo’s mechanisms.

One of the most striking features of Apollo is its hollow head—a feature designed to convey that Apollo isn’t a thinking entity in the way humans are. It’s a tool, albeit an advanced one. “The void in the head makes Apollo appear lighter, more approachable, and avoids the ‘uncanny ’ that many robots fall into,” Rolaton points out.

THE ROBOT OF OUR ELECTRIC DREAMS

The studio became obsessed with the project when it started working with Apptronik last September. Over the course of nearly a year, the team iterated the shape of Apollo’s face hundreds of times. Every aspect of it, from its concavity to the distance between eyes, was carefully modulated. Rolston recalls a particularly cute version of the head, with indentations on the cheeks that made it look like a monkey. It was an interesting concept, but it sent the wrong message. They wanted Apollo to be seen as advanced, not primitive.

At the same time, the team had to grapple with the challenge of making Apollo non-menacing. Some of the designs were reminiscent of skulls, especially the ones with convex faces. The concave, hollow face that they ultimately chose eliminates that threatening feeling. It’s softer and almost playful.

Apptronik’s CEO and cofounder, Jeff Cardenas, describes their ultimate fear test: Make Apollo stand silently behind a person. When the person notices the robot and turns around, does he or she feel threatened? With this design, the answer seemed to be no. And yet, nobody finds the face cute either. The team seems to have produced an emotionally neutral design, at least according to their tests with employees, collaborators, and clients.

A DIFFERENT KIND OF DESIGN

Apollo is designed to be an all-purpose robot. Although its first deployment will be in warehouses, to unload and palletize boxes and totes, its fate will take it across all types of labor you can imagine, from last mile package deliveries to supermarket restocking to the assembly and maintenance of complicated machinery in all types of conditions. For that, it needs to be able to perform at maximum precision and efficiency.

Unlike many robots that rely on pneumatic “muscles,” Apollo achieves that objective only using electrical components. Cardenas emphasizes that electrical parts offer a level of control and responsiveness that’s unparalleled. It’s what allows Apollo to perform tasks with human-like dexterity.

Its electric soul also allows for one of Apollo’s standout features: swappable batteries. We wanted to ensure that Apollo could work continuously without long downtimes, Cardenas explains. “The battery is targeted at a four-hour runtime, but it depends on what it’s doing.” The hot-swappable battery system means Apollo can keep going almost non-stop. The batteries attach to the robot’s back, and to change one requires simply grabbing it by the handle and swapping it out, much like the battery on an electric bike.

“If you’re lifting heavy stuff all day long, you can drain the battery faster. With normal activity, it has a four-hour runtime, which is kind of the minimum where our customers need us to be,” Cardenas says. “Then you can swap the battery out quickly. We’re targeting 22 hours a day, seven days a week of time.”

Apollo’s current tasks might seem rudimentary to the untrained eye, but they are foundational, Cardenas says. Handling boxes in warehouses, for instance, is a task that requires precision and reliability. “Apollo’s initial applications, like gross manipulation, are just the tip of the iceberg. These tasks lay the groundwork for what’s to come.”

A QUIET BOT

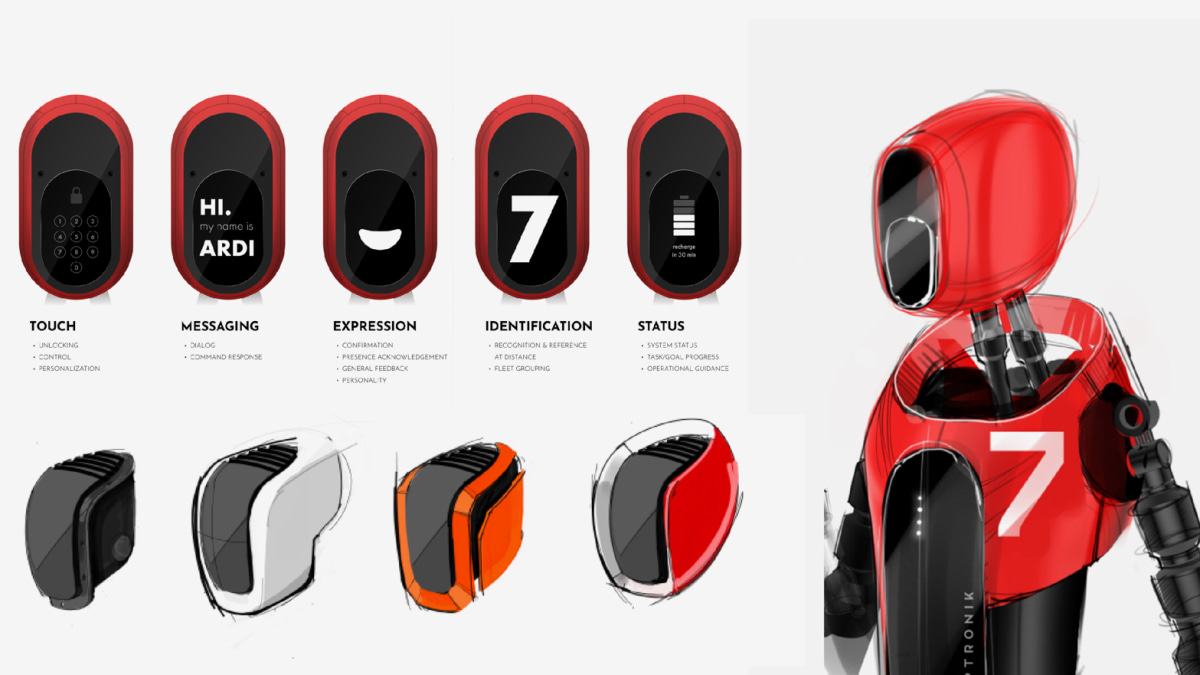

Unlike other humanoid prototypes, Apollo doesn’t talk. To communicate with its human coworkers, the bot uses an e-ink display that’s positioned behind the skeleton of its head and an OLED screen on its chest. The display is off most of the time except when it really matters—when Apollo has something to communicate, whether it is to answer a question or indicate a state. The OLED screen serves as an identification plate, showing a custom name and the vital statistics of the robot, like its current task or its battery level, which helps humans to quickly gauge its operational status.

Its nonverbal nature is a cornerstone of the user experience. “We wanted Apollo to communicate without words. The e-paper screen allows it to convey emotions, intentions, and simple messages,” Rolston says. The robot’s “mouth” can display words within a dialog bubble and certain icons. For example, Rolston highlights the use of the ellipses symbol, a universal sign of thought and pause, as something we’re familiar with from chat applications on our phones. “We wanted to give humans an indication that Apollo is processing or ‘thinking’ without making it too human or too cute,” he says.

This doesn’t mean that Apollo’s UX will not evolve toward something else once the technology is ready. The robot’s tasks are controlled using an interface on tablets or computers, so there are no commands. In other words: Apollo is not Alexa. That will come later. Which is exactly why the current language is reduced to this e-ink screen and symbols.

Cardenas tells me that they spent significant time on the software development part, focusing on how users can instruct the robot using tablets. The goal was to simplify its interface, making it as user-friendly and simple as possible. “Right now, a tablet or computer is the primary mode of interaction, but we’re looking at more direct communication methods for the future.”

THE OTHER HUMANOIDS

To understand the scope of Apollo’s achievements, you have to compare it to Atlas and Optimus. The first is “the Formula 1 car of humanoid robots,” according to Cardenas. He describes the robot made by Boston Dynamics as a super-advanced beast capable of viral choreographed feats in the lab. He believes a humanoid like Atlas is impossible to deploy in real work environments because of its experimental nature and its multi-million dollar cost. “We’ve always envisioned a world where robots could work alongside humans, not just in controlled environments but in real-world scenarios. Apollo is the embodiment of that vision,” he says.

Optimus, on the other hand, is years behind Apollo at this point. While Musk’s pipe dream was crudely announced in 2021 using a person inside a suit, two of Apptronik’s cofounders—Nick Paine and Luis Sentis—were already working in humanoids at the Human Centered Robotics Lab at the University of Texas at Austin in 2013. That was the year when they participated in DARPA Robotics Challenge, led them to work on Valkyrie, NASA’s first bipedal robot.

According to Carenas, working with NASA was a game changer because it gave them insights into building robots that could operate in challenging environments. This perspective has directly influenced Apollo’s design. And several robots preceded Apollo after Valkyrie, each contributing to the knowledge base that would eventually lead to Apollo’s creation. “Every robot we built was a stepping stone to Apollo,” he says. “It’s the culmination of several iterations, each one refining the vision of a machine that can seamlessly integrate into our world.” (Recently, Apptronik won a new contract with NASA to bring Apollo to market in 2024.)

JUST THE BEGINNING

A significant area of future development will be Apollo’s dexterity. The team at Apptronik is investing in refining the robot’s fingers to handle tasks that demand a delicate touch. Cardenas says that Apollo will be picking up a fragile piece of glassware and assembling intricate machinery in the future. “That’s where we’re headed. Increasing the dexterity of Apollo’s fingers is a priority for us,” he says.

The robot’s interaction with humans is set to undergo a transformation as well. “Our design already incorporates visual cues to help humans understand Apollo’s intentions,” says Rolston. “But as AI technology evolves, we’re looking at Apollo understanding and responding to human emotions and intentions in a much more nuanced manner.”

This evolution of AI is central to Apollo’s future. With local AI processing, real-time reactions will be possible, reducing the gap between input and response, ensuring Apollo can operate seamlessly in dynamic environments. This means that, while Apollo will be secluded in warehouses for now, we will see future versions doing everything a human can do, from working in an oil platform to disarming a bomb.

For now, though, the objective was to get the first affordable robot humanoid out of the lab and into companies’ hands (the company won’t share a price yet, but Cardenas believes that future Apollos should cost around $50,000 per unit for it to work for companies).

We will have to wait till 2024, when Apollo is fully deployed, to see if it can deliver on its promise. If it works out as Cardenas and Rolston believe, it will be the start an era that will see the long promise of robotics finally fulfilled: to save humans from some boring, stressful, or dangerous tasks. And dirty dishes, too.