- | 8:00 am

These giant, glowing carbon blocks bring clean energy to factories

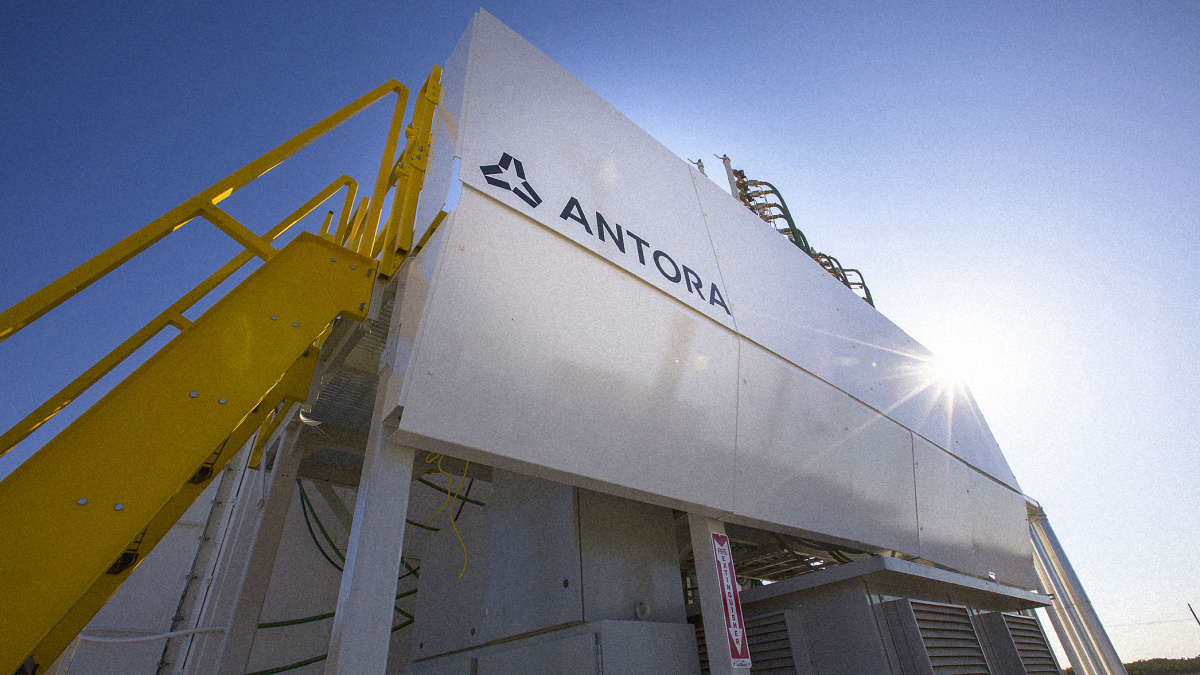

Industrial heat is a major source of emissions. In a new pilot, the startup, Antora Energy, is demonstrating an affordable way to change that.

A new type of tech designed to tackle one of the biggest sources of carbon emissions works a little like a toaster—if your toaster could reach more than 3,200 degrees Fahrenheit and heated up giant blocks instead of bread.

The device, called a thermal battery, is made by the startup, Antora Energy, which launched a pilot this summer to test the design. The startup wants to transform the hard-to-decarbonize industrial sector without increasing costs. A third of the energy used in the U.S. goes to heat in factories, from the natural gas that runs boilers in breweries to coal used in furnaces making steel.

In the past, the equipment couldn’t easily be switched to renewable energy, in part because solar and wind energy aren’t continuously available. “Industrial processes need to run 24/7,” says Andrew Ponec, Antora Energy’s cofounder and CEO. “That’s both for process reasons—some of them can’t be turned on and off easily—and it’s for economic reasons. Building a huge steel plant is very expensive, and so you need to run it 24/7 to recoup that investment.”

The thermal batteries are designed to store that energy inexpensively. Electricity from a solar or wind farm heats up large blocks made of carbon (aka graphite, the same material used in pencil lead). The blocks are already used in industry for other reasons, so they’re widely available—and very cheap. Inside an insulated container, the blocks reach ultra-hot temperatures, and then release the heat on demand to factory equipment. A single site could have between 10 and 100 units, each the size of a shipping container, filled with blocks that are roughly a meter long

By working in locations where there’s already extra renewable electricity available, the company can use that power when it’s cheapest. In California, for example, so much solar power is produced in the middle of the day that grid operators often have to cut it back. In the Midwest, there’s often energy wind power available. The combination of cheap materials and timing makes the system cost-competitive with the cheap fossil fuels that industry uses now.

“In areas where there are inexpensive renewables, we are competing directly with fossil fuels, and our customers are choosing us not because they want to be green—although in many cases they do—but because it actually is profit-making for them,” says Ponec. Erasing the “green premium” that often comes with new climate tech was a key requirement for the design of the system: The company knew that in order to scale as quickly as possible, factories would need a financial incentive to change.

At a site in California’s Central Valley, an electric utility is now testing the battery at a combined heat and power plant. The pilot has proven that the bricks can reach temperatures above 1,800 degrees Celsius, or 3,200 degrees Fahrenheit. That temperature “opens up pretty much every industrial process,” Ponec says. “About 99% of industrial heat is applicable with a system that goes that high.”

Manufacturing will begin next year, and the company plans to begin large-scale deployment in 2025.

In parallel, Antora is developing another version of the technology that can turn the heat back into electricity to run other industrial processes. The design uses photovoltaic panels—like solar panels, but instead of sunlight, it runs on the white-hot light beaming off the glowing blocks.

A handful of other startups are also developing thermal batteries for industry, including Rondo Energy, which plans to scale up what it says will be the largest battery factory in the world. Good policy could help the technology grow much faster. “This will not happen in a reasonable amount of time on its own without smart policy,” says Jeffrey Rissman, a senior director at the energy and climate think tank, Energy Innovation. The Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits that apply to the tech, and governments can also help in multiple other ways, including procurement programs that require suppliers (for example, companies supplying cement for roads or buildings) to adopt the technology.

Climate solutions like electric cars or solar panels have gotten more attention, but it’s just as critical to tackle heat in factories, Rissman says. “You cannot achieve a stable climate without addressing industrial emissions,” he says.