- | 9:00 am

The beauty industry is a mega-polluter. This innovative solution could change that

The beauty industry churns out millions of pounds of unrecyclable plastic every year. Can better data get it to stop?

When my jar of Glossier concealer ran out recently, I stood in my kitchen for five minutes, trying to figure out if I could toss it in the recycling bin. I assumed that the metallic cap was not recyclable, but I squinted to see if the glass jar had a recycling symbol on it. It didn’t, so I tossed it in the trash, feeling a wave of guilt wash over me.

Millions of people go through this experience every day as they ponder what to do with their empty shampoo bottles and lipstick tubes. The beauty industry churns out an estimated 120 billion products every year and the vast majority of packaging ends up in landfills. The problem is twofold: Many bottles and tubes are simply not recyclable, and many consumers don’t bother recycling those that are.

But consumers are becoming aware of their devastating impact on the planet, and 60% say they will pay more for a product with sustainable packaging, according to a 2020 McKinsey report. Customers are gravitating toward brands that are eco-friendly, with responsible supply chains and packaging that is easily recyclable. This has kickstarted a movement in the beauty industry to push for more sustainable practices.

We’re seeing signs of change across the industry. Retailers incuding Sephora and Nordstrom now have recycling bins in-store so customers can recycle beauty waste. Meanwhile, the nonprofit organization, Pact, has brought together 150 beauty brands (and counting) that have committed to sharing best sustainability practices and providing recycling solutions for hard-to-recycle plastics. In the world of technology, the startup Bluebird has built AI software that allows brands to instantly identify the carbon and waste impact of their packaging. This week, Pact and Bluebird have joined forces to ensure all Pact members have access to this data.

These are all steps in the right direction, but it also raises bigger questions. It’s unclear whether it is possible for the beauty industry to reduce its impact with companies churning out more products every year, convincing consumers they need them. The average woman owns a whopping 40 beauty products, but uses only 5 regularly. For real change to happen, consumers don’t just need to recycle their products; they need to drastically cut down on the number of products they buy in the first place.

THE DATA DEFICIT

Since the 1980s, when the U.S. government introduced curbside recycling programs across the country, Americans began to learn what kinds of food packaging can be recycled. There are currently no laws mandating that companies make packaging out of recyclable materials, but over the past four decades, it has become the norm for brands to do so. Soda, beans, and sardines are sold in easy-to-recycle aluminum tins; pickles, pasta sauce, and olives are sold in glass jars.

In the beauty and personal care industries, however, companies haven’t made recycling a priority. (For instance, Colgate only developed fully recyclable toothpaste tubes last year, after 150 years in business.) As a result, many beauty packaging suppliers don’t prioritize recyclability in their design process.

One big hurdle to recyclability is that there isn’t standardized packaging in the beauty industry, the way many milk and juice brands use a generic cardboard carton. Instead, beauty suppliers offer a wide range of tubes and bottles, made of diverse materials, only some of which are recyclable. And in order to stand out on the shelf, brands often design their own customized packaging with special caps and unusual shapes—most of which are not recyclable. Then, there’s the fact that special features like pumps and spray nozzles are made of many complex materials, making them hard to recycle as well.

Globally, only 9% of all plastic is recycled, and experts believe that in the beauty industry, the proportion of plastic recycled is even lower. “Most beauty packaging is too small to be caught by municipal recycling facilities,” says Carly Snider, Pact’s program manager. “And a lot of packaging is made from mixed materials that are also hard to recycle.”

Jamie McCroskery, who cofounded Bluebird three years ago, previously worked for Glossier and observed how mind-boggling the process is for beauty brands to choose packaging. “Even if brands want to become more sustainable, it is hard for them to wade through all the different packaging options and figure out which one is optimal,” he says. “We launched our company to make it easier for brands to quantify recyclability and climate impact when making these decisions.”

Bluebird spent a year and a half gathering data about the different packaging options on the market, delineating what they are made from and where their materials come from. Even within the realm of plastic, there are dozens of options that brands can choose from—ranging from PET (Polyethylene Terephthalate), which is clear, reusable, and recyclable to LDPE (Low-Density Polyethylene), which is widely used in squeezable bottles but is not recyclable.

Brands can now upload images of their products to Bluebird’s website to learn where it was sourced and how much carbon was emitted in shipping it; they can also learn whether it is recyclable and reusable. In some cases, brands have used this information to find alternative packaging that is recyclable or that comes from a local supplier, to reduce its carbon footprint. “Tools like this are particularly important to small brands that don’t have the resources to do this kind of research in-house,” says Maxine Bedat, founder and executive director of the New Standard Institute, a think tank that seeks to advance sustainability through data.

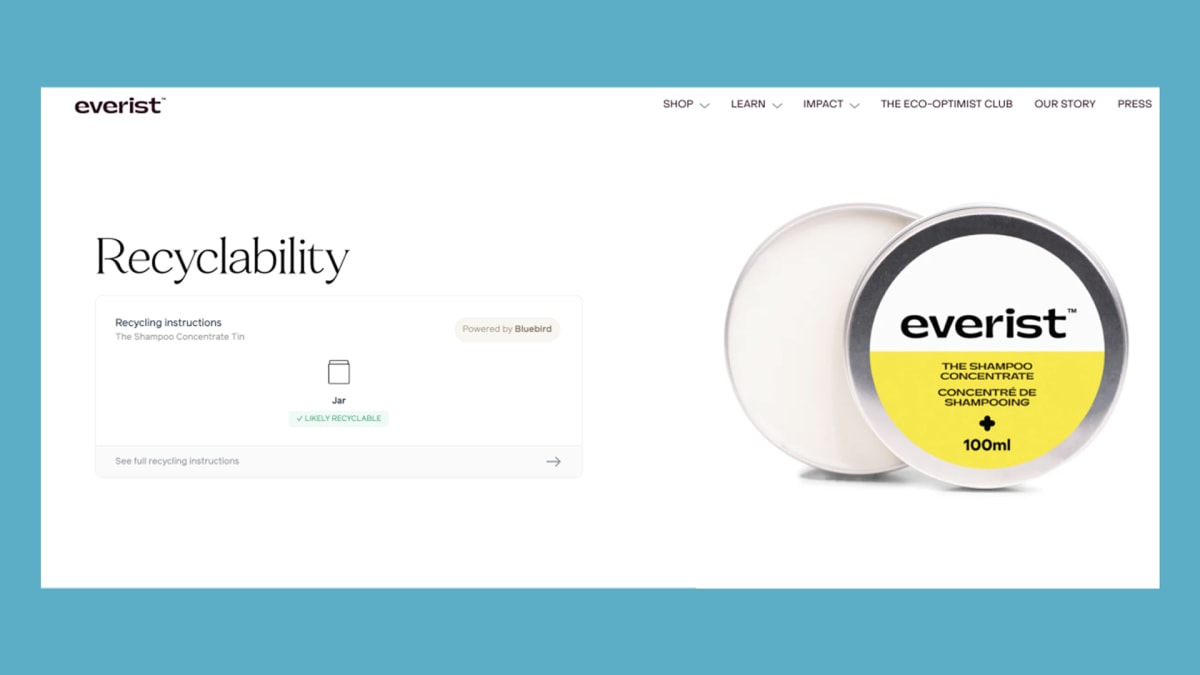

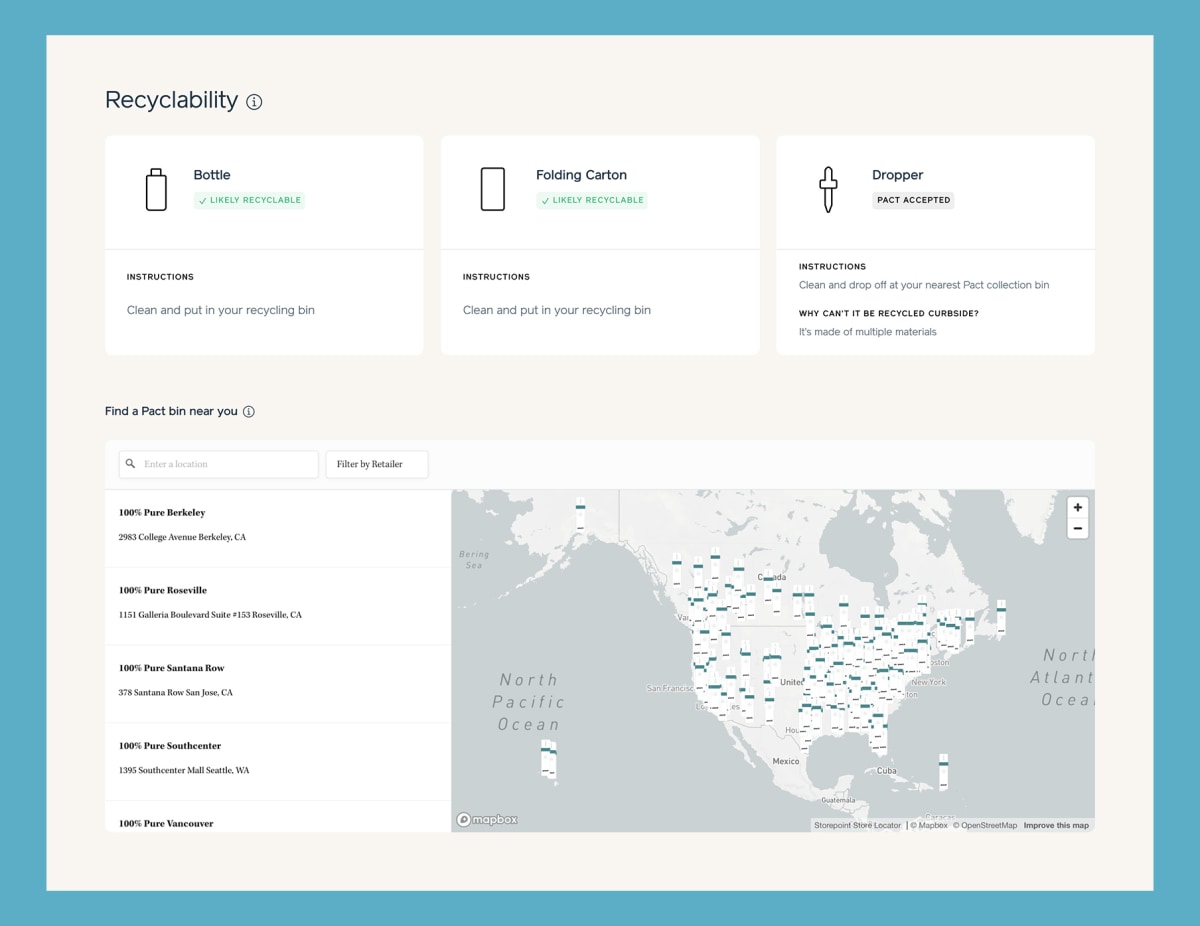

But an important part of Bluebird’s platform is helping educate consumers about the sustainability of beauty packaging. Brands who use Bluebird’s software can upload information on the product website that explains its environmental impact and how to dispose of it. Take the skincare brand Versed, for instance, which has incorporated Bluebird into its website. When you look at its bestselling resurfacing mask, you learn that you can rinse out the cap then throw it in the recycling bin, but the jar must be thrown in the trash. “More data is good,” says Bedat. “The average person doesn’t understand that not all plastic can be recycled, which creates lots of problems throughout the recycling process.”

Perhaps more surprisingly, brands can opt to get a comprehensive sustainability report on each of its products that it can then share with its customers on its own website. Versed, for instance, reveals that this mask performs worse than average in terms of its carbon and waste impact. “Brands that use our service believe it is important to be transparent with their customers about where they stand because it promotes trust,” says McCroskery. “But there’s only a small, vocal minority that digs into these reports. The vast majority of people just want to know you care about the impact of your business.”

GETTING TO A TIPPING POINT

Pact is trying to get more beauty brands to care about sustainability. The nonprofit organization was founded by two beauty veterans, Victor Casale, cofounder of MOB Beauty, and Mia Davis, Credo’s VP of sustainability. Their goal is to bring the beauty industry together to promote as much recycling as possible. Right now, there are more than 150 brands that are members of the Pact Collective, including L’Oreal, Fenty Beauty, and Benefit.

Members must educate consumers about how to recycle products and provide ways to responsibly dispose of packaging that cannot be recycled at home. Pact now has nearly a thousand beauty collection bins at retail stores, including Sephora, where consumers can dispose of hard-to-recycle packaging. So far, it has collected 156,762 pounds of material. “We know that different packaging types are inevitable within beauty at this point,” says Snider. “We don’t have the solutions to move entirely away from plastic, so we need to find ways to collect materials that are destined for the landfill and find alternative uses for it.”

But ultimately Snider says that these recycling programs are just a stepping stone to broader change. Ultimately, brands need to stop using as much plastic, and move towards solutions like reusable packaging. “We can’t recycle our way out of this problem,” she says.

Bedat agrees. She argues that the problem with the beauty industry, much like the fashion industry, is that brands are pushing out too many products. While it’s important to be reducing the impact of packaging, the more pressing goal should be to reduce the overall volume of products produced in the first place. And yet, beauty brands thrive on marketing hot new products, many of which we don’t need and won’t actually use. “On TikTok, beauty influencers talk about the beauty products they’ve actually finished, as if it is some great feat,” Bedat says. “Shouldn’t we be using all our skincare products until they’re finished?”

Still, McCroskery believes that change is sweeping over the beauty industry, albeit slowly. People are demanding more sustainable options, and brands rethinking their supply chains. And over time, with more education, he believes they will change their consumption behavior. “Changing the infrastructure of the beauty industry isn’t going to happen overnight,” he says. “But consumer education will drive change.”