- | 9:00 am

How Lockheed Martin designed the X-59, the world’s weirdest, quietest supersonic jet

In a feat of engineering, the X-59 travels faster than the speed of sound, while making barely any sound at all.

The Lockheed Martin X-59 is probably the strangest airplane ever designed. Its razor-sharp nose takes half of the airplane’s length; there’s no cockpit in sight; the wings are tiny compared to the entire fuselage; and its oversized tail engine looks like a weird hump about to fall off. Of course, there’s a method to this madness. The design is the secret sauce that has produced a true unicorn: a supersonic jet that doesn’t boom the hell out of people and buildings on the ground.

The sonic boom is a phenomenon that has long been the Achilles’ heel of supersonic flight. When an aircraft travels faster than the speed of sound, the compressed air molecules against the body of the plane produce shockwaves that merge to form a sonic boom, a loud and disruptive noise heard on the ground. This noise has historically been a significant impediment to the commercial viability of supersonic flight over land.

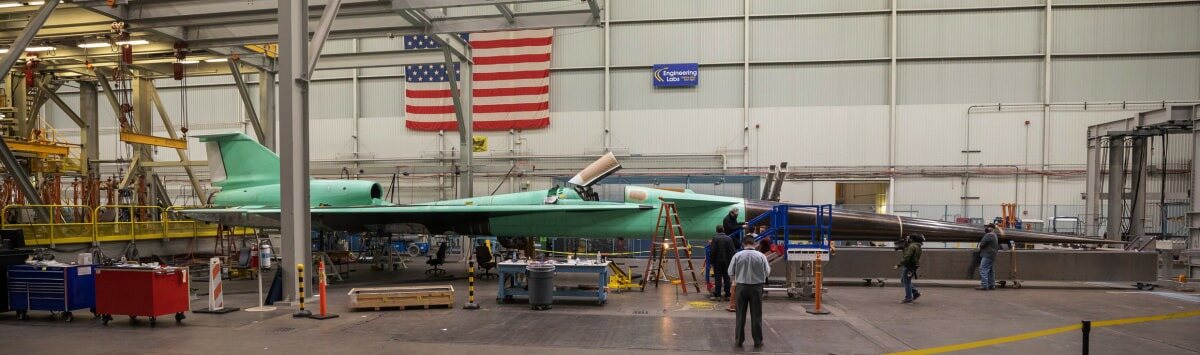

[Photo: Lockheed Martin]

The X-59, developed alongside NASA, is designed as an experimental jet that NASA will use to test just how big of a boom people on the ground are willing to accept from a supersonic aircraft. According to Dave Richardson, the program director for X-59 at Lockheed Martin, with this new design, people shouldn’t expect much of a boom at all.

The X-59’s “quiet” supersonic boom isn’t made possible by expensive magical materials or exotic engines, Richardson explains. “There is no radical technology in the airplane itself. It really is just the shape of the aircraft.” And if the shape looks more like an anime alien spaceship than an actual vehicle created by human beings, that’s because it was dreamed up in another dimension—by computers and humans—through special software created by the Bethesda, Maryland, company’s engineers.

[Image: Lockheed Martin]

DESIGNING SUPERSONIC FLIGHT

Many of the problems that plague supersonic flight can be traced back to the Concorde, the famous supersonic passenger jet that could travel from New York to London in a mere three and a half hours. When the Concorde first took flight in 1969, people were enthralled by the idea of super-fast air travel. It sounded like a technological marvel . . . until they heard the actual sound.

[Photo: NCJ Archive/Mirrorpix/Getty Images]

As the passenger plane zoomed overhead and broke through the sound barrier, it sent a deafening boom to the ground below. People described the sensation of a bomb dropping. Glass windows shattered and doors trembled.

Unlike the X-59, the Concorde wasn’t designed to be quiet. Its delta-wing design—with two very large triangular wings along its entire fuselage that made it look like a paper airplane—and powerful engines were contributors to the sonic boom. As planes started to go supersonic over the continental U.S., the sound explosions became so much of a problem that Congress banned supersonic flight over land in 1971, a move that was later followed around the world.

The Concorde continued to fly until it was decommissioned in 2003, but most airlines couldn’t justify the cost of operating the airplane if its supersonic abilities could be used only over water. “The real breakthrough for supersonic flight would be to be able to fly over land again so that you have those long routes where that supersonic flight is more advantageous,” Richardson says. So that’s exactly what Lockheed Martin set out to build.

[Photo: Lockheed Martin]

NEED FOR SILENT SPEED

In the decades after Congress passed the legislation banning supersonic flight over land, NASA has been on a mission to muffle supersonic booms. But it wasn’t until recently that a silent supersonic jet became possible. Richardson says that’s thanks to high-speed computing and machine learning models that can accurately predict the interaction of the sonic shocks and how they propagate down to the ground from an altitude of 50,000 feet.

“That’s not something that we had the ability to do some time ago,” Richardson tells me. “We could have designed this kind of airplane, yes. We could have put it in a wind tunnel, but we would have had to iterate in the wind tunnel hundreds or thousands of times at a huge expense and many more years, versus doing it in the computer today.”

With this new technology in hand, NASA sensed an opportunity to repeal the federal supersonic ban. It launched a program called Quesst (Quiet Supersonic Technology) to design and build an X-59 research aircraft that reduces the explosive sonic boom to a gentle thump. In order to convince Congress to bring supersonic flight back into the mainstream, NASA knew it had to turn its low-boom research into an actual experiment that would demonstrate that an airliner could beat the speed of sound without breaking windows, annoying millions of urbanites, and giving cattle heart attacks.

The initial design proposal by Lockheed Martin [Image: NASA/Lockheed Martin]

The initial proposal by Boeing [Image: NASA/The Boeing Co.]

In 2016, NASA asked Lockheed Martin and a host of other companies to submit a proposal for a test airplane that could demonstrate that supersonic flight over land was safe and as silent as regular subsonic airliners. The target was to make a plane with a boom of just 75 PLdB, a volume unit that measures how people perceive sound as opposed to the actual decibels produced by the sonic booms. A 75 PLdB is the equivalent of hearing a dishwasher for less than a second. For comparison, the Concorde’s PldB was 105, or as loud as listening to a chainsaw at full power.

In 2018, NASA awarded Lockheed Martin a $247.5 million contract to design, build, and deliver the low-boom X-plane. The plane received its official moniker, the X-59 Quesst, from the U.S. Air Force in June 2018, but the company still had a long road ahead of it to develop a truly quiet supersonic jet.

“The genesis of the X-59 low-boom flight demonstrator comes from NASA as part of the growing interest in faster international travel,” Richardson says. “My daughter used to live in Japan, and flying to Japan took forever. And all of us have all been on these long flights where we wish we could be [at our destination] and we would pay more money to get there now.”

[Image: Lockheed Martin]

THE LONG RUNWAY TO THE X-59

Well before Quesst, Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works—its legendary advanced aerospace design group—had already been working on what would eventually become the X-59. Back in 2013, the plane was known as C100, and it looked a little bit like a shorter version of the Concorde with the engine right on its back, splitting a V-shaped tail.

Designers used software to optimize details like the shape of the wings, the configuration of the tail, and the length of the nose. “[The software] would inform us what we needed to do on the airplane,” Richardson recalls. Eventually the CAD design turned into a scale model, and the team tested it in a wind tunnel where engineers could apply their learning to the following iteration.

[Image: Lockheed Martin]

Next came the C435 mode, which used the V-tail design but had a much longer body with smaller wings and a sharper pointy nose. Then the C506, which got rid of the V-tail in favor of a traditional airplane tail after they realized that the V made it harder to maneuver the airplane, even though it was better at reducing the sonic boom.

By 2015, the team had a design for the C603, which added a canard—those two little winglets that you can see near the cockpit—at the end of the nose in the X-59. This model also pushed the engine farther back and set the wings at two different angles, first going up and then down around their midsection. The C605 was the final prototype that informed the preliminary design of the X-59.

[Photo: Lockheed Martin]

Through all of these iterations, Richardson and his team learned a few important lessons about designing for supersonic boom. First, the heavy, bulky parts of the plane needed to be as far back as possible. “We really put nothing out in the front, but we want to have that long, fine ratio,” he says. This resulted in an extremely fine nose and body, with no surface interruptions that can produce noise when the plane breaks the sound barrier. “You want to be able to stretch out and manage the different shocks across the length of the airplane,” he adds.

[Photo: Lockheed Martin]

They also learned that anything that causes discontinuity in the airplane’s shape—for instance a windshield or canopy—can add to the boom effect. This led them to get rid of the windshield altogether. Instead, the X-59 uses an external vision system, which is the only advanced technology in the plane, according to Richardson. The pilot navigates using a camera, viewing the outside through a large display. This system had to undergo rigorous certification by the Federal Aviation Administration for use in the national airspace.

Despite their best efforts to create a streamlined body, the team found that bulges were inevitable. Richardson describes how the inlet for the engine was placed on top of the plane so the shock that’s generated goes up into space rather than down to the ground. (This is what happened with the Concorde’s engines, which were under its wings.) The same thing goes for any actuators, whose position on top will send shocks up instead of down.

[Photo: Lockheed Martin]

BUILDING THE X-59

By November 2018, Lockheed Martin had initiated the machining of the X-59’s first part in Palmdale, California. Major structural components were assembled by May 2019. Fast-forward to November 2022, and the General Electric F414-GE-100 engine—which powers the U.S. Navy F-18’s Super Hornet—found its place in the X-59. The aircraft has since undergone a battery of tests, from weight checks and fuel system evaluations to ground vibration assessments. Remarkably, the X-59 weighed in below the anticipated weight, a rare achievement in aircraft development that surprised the entire team.

However, the journey hasn’t been without its challenges. Currently, the X-59 is in the system checkout phase, ensuring all systems are seamlessly integrated and functional. A planned maintenance and modification stand-down was needed due to parts that took five months to arrive. This delay pushed the aircraft’s inaugural flight, initially slated for December 2023, to early 2024.

[Photo: Lockheed Martin]

We will have to wait a little longer to see the first flight of this magnificently weird airplane. After that, there will be multiple tests in which the the X-59 will be flown over cities and rural areas, the team measuring decibels andgetting feedback from people on the ground.

If they achieve their objectives, there’s no reason why aircraft manufacturers can’t take the concepts they discovered and turn them into commercial airliners, Richardson says. In fact, one of NASA’s requirements for the project was that Lockheed Martin provide an airliner design. Lockheed’s vision for commercial supersonic air travel is a 200-foot-long (double the length of the X-59) twin-engine model for 44 passengers.

“I think the biggest challenge that anybody who would go and develop one of these airliners would have is finding an engine that would fly at Mach 1.8 without an afterburner and be large enough for an airplane of this size,” Richardson says, but noting that it is doable.

“If there are people who see the market for it and have the investments in their company to go forward and develop an aircraft, they could start right away, as soon as the supersonic ban laws are repealed,” he says.

Someday, people might be able to look up and see an alien shape in the sky, with the X-59’s design transcending experimental nature and ushering in a new era for high-speed travel across the globe.