- | 8:00 am

Could this goofy cartoon help doctors save lives in the OR?

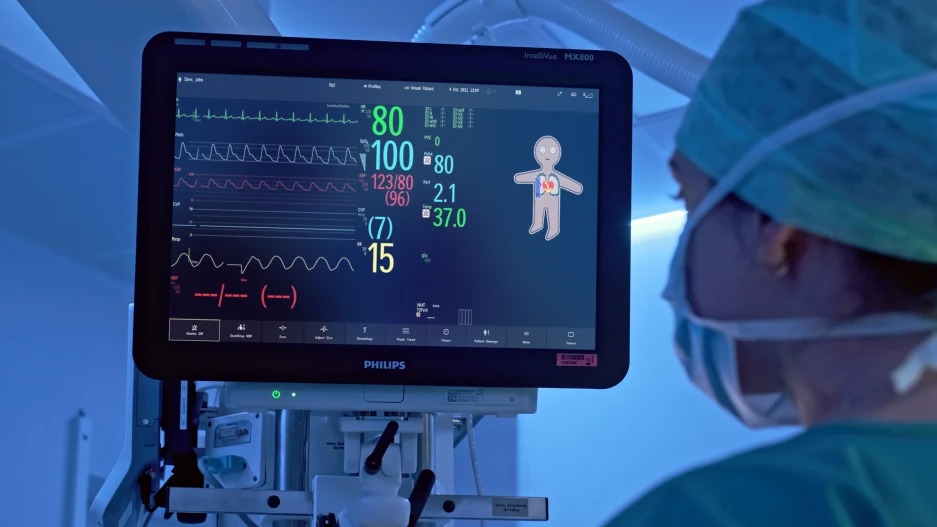

A typical patient monitor is a jumble of graphs and numbers. This cartoonish avatar designed by two anesthesiologists from the University of Zurich and Philips aims to simplify things.

In the late ’70s, NASA and the U.S. Air Force developed a system that revolutionized aviation. Known as synthetic vision, it provided pilots with a real-time, computer-generated image of their surroundings and made it easier to fly in poor weather and low-visibility situations. Now, a team of anesthesiologists from the University of Zurich wants to use similar strategies to help medical providers make faster, better decisions in the operating room. They’re doing that by redesigning the user interface of patient monitors.

The Visual Patient Avatar was created by Dr. David Tscholl and Dr. Christoph Nöthiger together with tech behemoth Philips. The idea, as Tscholl explained during a recent live demo, is to give medical providers a quick and easy way to gauge a patient’s condition by creating a “digital twin” of the patient on the screen.

Patient monitors are a mainstay in every hospital. They are mostly found in the OR, where vital sign changes can happen quickly, but they are also used in various critical care areas, recovery rooms, dialysis centers, and the ER. Conventional monitors display a patient’s vital signs through graphs and numbers. The Philips system doesn’t forgo the numbers, but it couples them with an avatar that looks like a cartoonish, animated silhouette and is oddly reminiscent of a gingerbread man ringed by a fine white border.

The silhouette will move and vary in color and shape to reflect the patient’s status: If their blood pressure is too high, the silhouette will pulsate outside the white border. If they desaturate and their blood oxygen levels drop below normal, the silhouette will turn purple as a patient would in real life. According to the scientists, the system is easy to learn and only requires a short training video.

The goal here is to decrease workload and increase situational awareness, which is responsible for 81.5% of anesthesia-related errors. To have situational awareness means to understand what is happening, what it means, and how it might change in the future. It forms the basis of good decision-making, but it can be influenced by a number of factors including experience, external stressors like time-pressure in a high-stake environment, or even personal problems.

Tscholl first thought of the idea for the Visual Patient Avatar more than 10 years ago. In 2012, Tscholl was an anesthesia trainee who also had a commercial pilot’s license. While flying a plane one day, he realized how much more confidence the synthetic vision system inspired in him as a pilot, and he wondered if some kind of patient avatar could achieve the same for anesthesiologists. He drew a silhouette on a napkin, then took it to his colleague, Nöthiger.

The scientists spent five years researching and developing the avatar before Philips got involved around 2017. They tested the product with hundreds of participants across several hospitals, and published their findings in more than 15 studies. Most tests were done in a real operation room but with simulated patients, though Tscholl says his team is running studies with real patients as we speak. The results will be available at the end of next year.

The findings from the other studies appear to be promising: Compared to conventional monitors in identical scenarios, the avatar more than doubled the number of vital signs that participants could remember after looking at the monitor for 3 seconds and then for 10 seconds. During the first use of Visual Patient Avatar, 73% of all vital sign information was correctly identified. The scientists also received positive feedback from various colleagues, including pediatric anesthesiologists, who noted that the avatar is a welcome distraction for young children who understand that this is their bodies being visualized on the screen.

The Visual Patient Avatar is already installed in a handful of hospitals in Western Europe and available on select Philips monitors across 185 countries. (FDA clearance in the U.S. is expected soon.) Customers who already have the right patient monitors must upgrade to the latest software then have the option to purchase the Visual Patient Avatar, though Philips declined to share the exact cost as it varies based on a number of factors.

It’s too soon to quantify the kind of impact the avatar could have, but history may hold a few lessons. This isn’t the first time that scientists or even medical technology companies have tried to liven up numerical outputs with graphical displays. Matthew Weinger, a professor of anesthesiology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (who wasn’t involved in the Visual Patient Avatar), says the idea dates back to the 1980s.

In fact, Weinger himself introduced animated graphical displays in 1992. His idea included a kind of precursor to mixed-reality glasses that anesthesiologists would wear right above eye level: the glasses would provide a snapshot of the patient’s vitals in the form of graphic displays of the lungs, heart, and kidneys. Weinger says the idea didn’t materialize as the technology wasn’t ready back then, though it “probably is now.”

According to Weinger, medical technology company Edwards Lifesciences was the first to commercialize anatomical graphical displays in the 2010s with its cardiac output device that visualizes the way blood circulates through the brain and the heart. Various other companies have since introduced graphical displays, but the Philips version may be one of the first to propose an image that depicts the full body and integrates more variables.

And yet, despite general evidence suggesting that visual outputs are easier to read than numbers, few companies have succeeded to commercialize such systems. For Weinger, that failure is likely due to familiarity with traditional equipment, but also potentially to self-esteem: “Making a task easier is not always well received by skilled professionals who are proud of their expertise including the ability to distill complex data into meaning,” he told me via email. “I am thus skeptical of the likely commercial success of the new Philips display (but would be thrilled if I was proved wrong).”

Weinger hasn’t tried the Visual Patient Avatar yet, but looking at the company’s website, he seemed concerned about it being too cartoonish: “Not sure if that will be well received as [it] could be interpreted as trivializing the task,” he said.

I had wondered the same. Working in the OR isn’t child’s play, so why choose a user interface that looks childish? In response, Tscholl offered a reminder that doctors are humans, too, and all adults remain children at heart. “For me, I love the idea of making the hospital environment more playful and a little bit softer somehow,” he said. “If you have this avatar on the monitor, then you are always reminded you are treating a patient here.”