- | 8:00 am

Why Adobe’s flubbed $20 billion acquisition of Figma matters

Adobe’s biggest deal in history just fell through. It could impact design software for years to come.

This week, Adobe and Figma announced their joint decision to end plans for a $20 billion acquisition. Whereas Adobe had strategized to bring Figma into its suite of creative tools, adding the world’s hottest UX prototyping platform to its arsenal, European and UK regulators pushed back on this mass consolidation of market power. “We no longer see a path toward regulatory approval of the deal,” concluded Figma CEO and cofounder Dylan Field in an open letter this week.

At a glance, that’s the entire story. Adobe pays Figma a predetermined $1 billion kill fee on the deal, and it’s all just another piece of historical corporate trivia.

What happened? Organizations like the U.K.’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) were concerned about the formation of an anti-competitive creative software monopoly. In Adobe’s response, you can read the company’s now-moot plea. It includes arguments ranging from Adobe’s own failures to gain a foothold with its own Figma competitors, Adobe XD and a now defunct platform dubbed Project Spice, to an assertion that Adobe would need to divest in its marquee software brands, Photoshop or Illustrator, to appease CMA complaints and bring this deal across the line. Adobe wrote the latter would be “wholly disproportionate” to address anti-competitive concerns. (Adobe and Figma both declined to comment for this article.)

“We’re not surprised the deal fell through given Adobe’s stated resistance to the European and U.K. regulatory requests for divestments,” says Forrester VP and research director Ian Jacobs. “That was just a bridge too far for Adobe, and even Figma’s innovation and momentum in the design community seemingly was not worth starting to carve up the company.”

But beyond debates about market share, what more is there to say now? A lot! Put it this way: The biggest deal in Adobe’s history just fell through. And I’d highlight three points to consider about the story that aren’t being discussed much yet—that explain how this failed deal could impact the design community, and the software that supports it, for years to come.

1. FIGMA MIGHT NOT BE WORTH $20 BILLION, POST AI BOOM

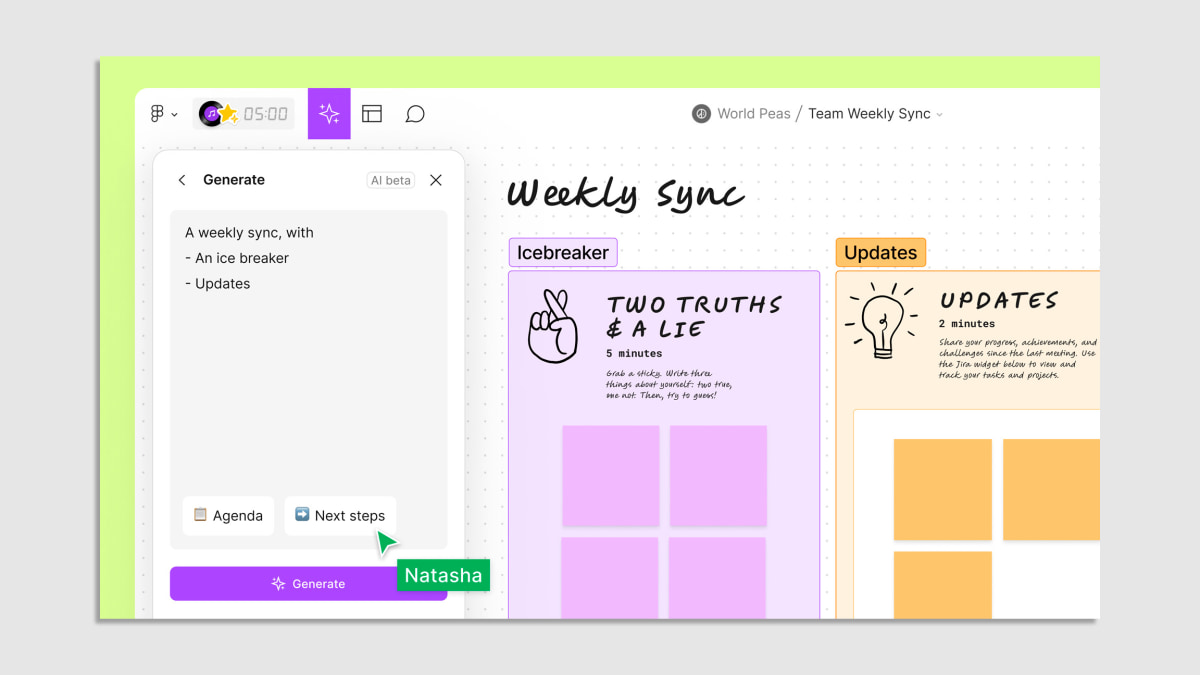

Timing is everything, and this deal could not have kicked off at a worse time for Adobe. Keep in mind that Adobe’s announcement to acquire Figma was made in September 2022. That was only months after the release of image models DALL-E 2 and Midjourney, and a month before the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in November—which would amass 100 million users within the next 60 days. Now, a year out of the generative AI explosion, it’s still too early to crown any winners. But tech giants are shuffling billions of dollars internally to own whatever comes next. AI is set to change the way all software is designed, and it has already proven semi-competent at interface prototyping, the bread and butter of Figma.

Another way to phrase this thought experiment: Microsoft has invested $13 billion in OpenAI to date, in a move most are heralding as a Google-rocking, generationally clever investment on Microsoft’s part. In that climate, is Figma worth $20 billion?

“I suspect Figma would not get that same valuation in today’s market that they got a year and a half ago, simply because AI makes it so much easier for companies in that stage and for incumbents to compete,” says James Currier, general partner at NFX, a leading VC firm in AI software.

That said, Currier is unconvinced that the deal falling through is some outright win for Adobe, when in fact, Figma’s capabilities and community would both be quite valuable to the company. And Adobe still has a Figma-sized hole in its offerings.

“I think in the short term it is probably not worth twenty, and in the long term, it might be worth more,” says Currier. “So, is it a fair valuation? It’s hard to say.”

2. FIGMA HAS IT A LOT HARDER NOW

Adobe is an approximately $260 billion (market cap) software company. It’s publicly traded, facing the ever tricky scrutiny of Wall Street, and it will be challenged by countless software startups to continue its dominance into the next decade. But Figma just lost out on a generation-defining software deal. It has lost its chance to roll comfortably into a tech giant with its own R&D budget. Adobe spends roughly $3 billion a year on this work.

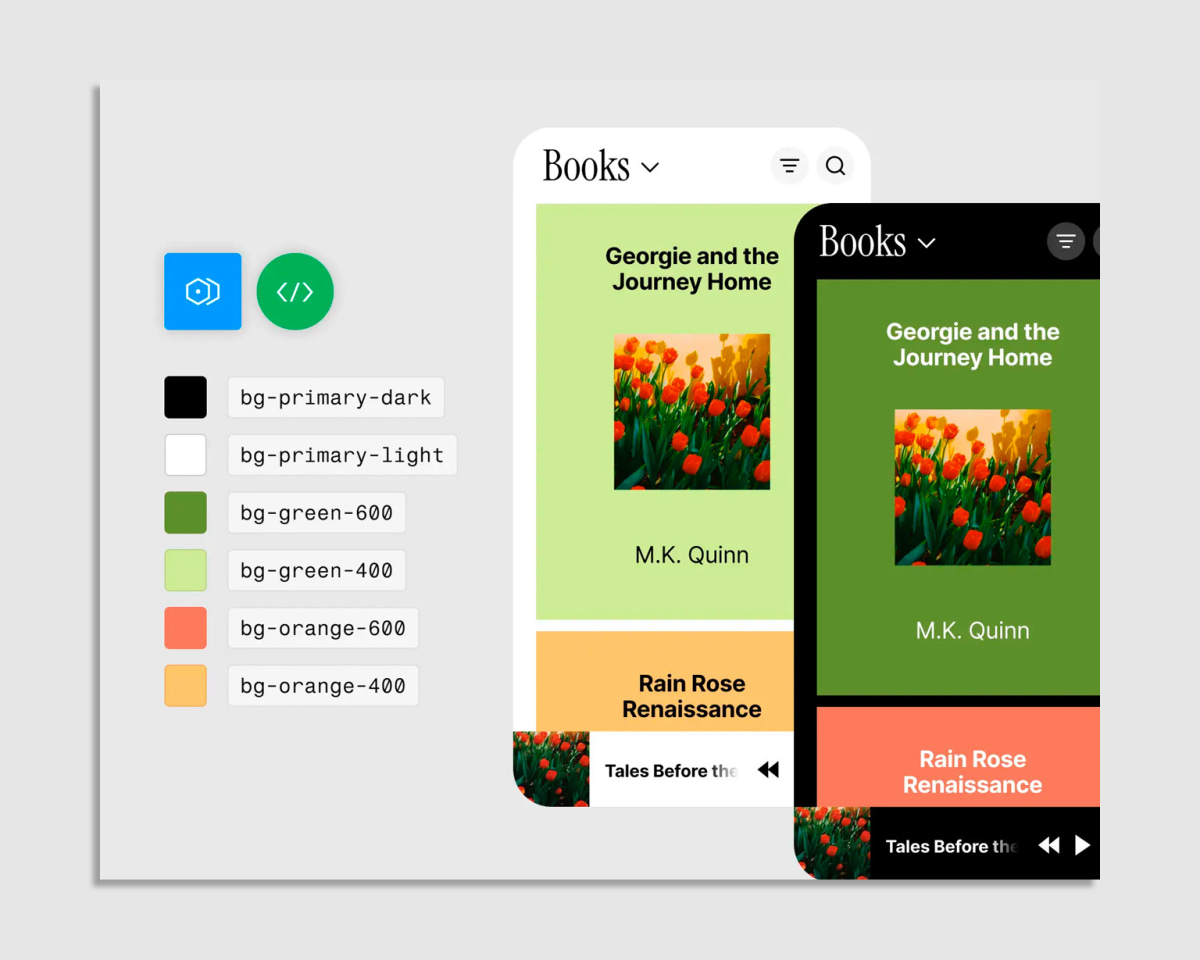

“In the particular case of Figma, had the deal gone through, it—and all the designers out there—would have benefited from the gobs of resources Adobe has been plowing into AI and generative AI, in particular,” says Jacogs. “Figma was, of course, pouring its own dollars and people into AI research and has already shown many promising AI-driven features. But it’s a matter of scale—Adobe with its much larger size has a much larger research budget. Now, Figma will need to keep its rapid innovation pace without as much cash or research synergy.”

This is not to undermine Figma’s own ability to innovate, or its proven understanding of its target market. The point here is that Figma is reportedly on track to make an incredible $600 million in revenue in 2023, but that’s a pittance compared to the blank check investments we’re seeing within AI. Adobe offered Figma a clear runway to evolve and compete in this industry. Adobe silenced certain existential threats to the company. Now, we will see Figma carve its own path.

3. THERE’S STILL A HOLE IN THE DESIGN TOOLS MARKET

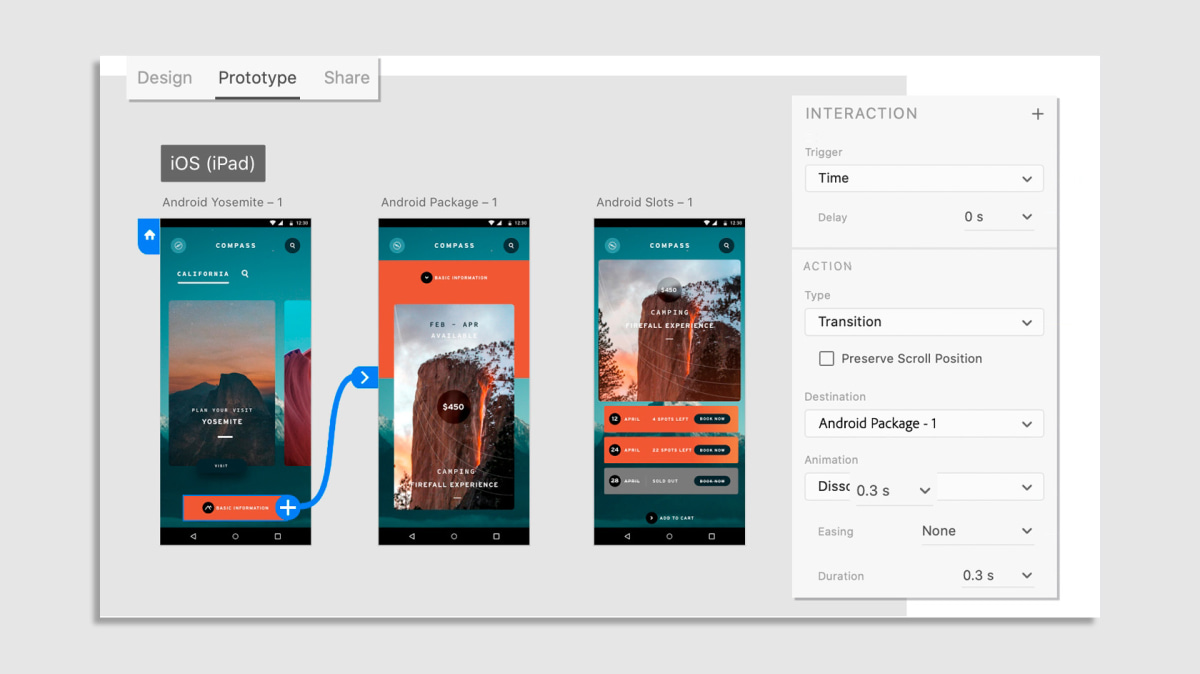

You have an idea, and alongside your design team, you want to build a functioning prototype to prove out the product while it’s being engineered. Ideally, you could do this in a single fluid piece of software (or related softwares), and this is the exact sort of end-to-end production workflow that Adobe was trying to solve by acquiring Figma.

Now Adobe doesn’t have Figma, and it’s safe to say it doesn’t really have that workflow solidified, either. So, there’s still an opening in the market for some company to fill this gap.

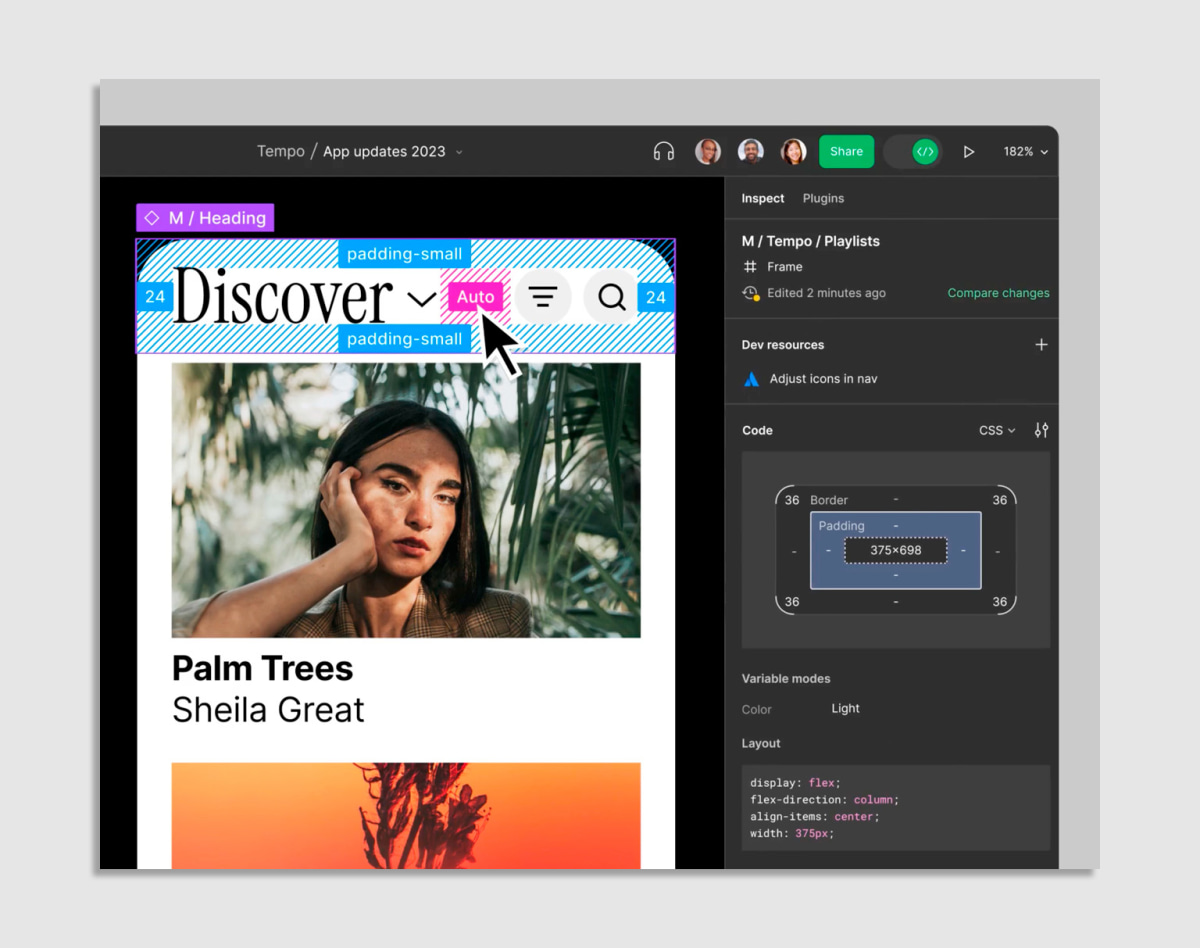

“The key thing for the design world here is that the consolidation of functionality into an overall design workflow toolset will continue,” says Jacobs. “Collaboration tools will also have prototyping capabilities. And prototyping tools will also have direct connections to higher fidelity design tools. That would have happened whether Adobe managed to acquire Figma or not. And yes, the two companies will now just need to keep competing, but that competition is mostly at the edges of what they each do.”

It seems impossible for Figma to build out all of Adobe’s fine-tuning graphics software on its own, and it’s proven challenging for Adobe to build out a sought-after prototyping tool on its own. The result is something of an innovation impasse. Some entity or other seems destined to create this workflow and own the space, and it’s feasible to imagine a next generation AI-based design tools company disrupting Adobe and Figma both.

But Currier—an investor who admittedly benefits from the payouts of major acquisitions—argues that the CMA icing the Adobe/Figma deal could ultimately thwart investment in design tools, because Adobe isn’t the Microsoft or Google-sized company most people might consider when concerned about monopolies. And if Adobe can’t buy your unicorn startup, then who can?

“This puts a chill on venture investment—it puts pressure on mid-tier companies like Adobe or Figma struggling to survive against true software behemoths,” says Currier. “There’s some downside to that decision.”