- | 4:41 am

How the creator of Hulu’s ‘The Dropout’ tried to think like Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes

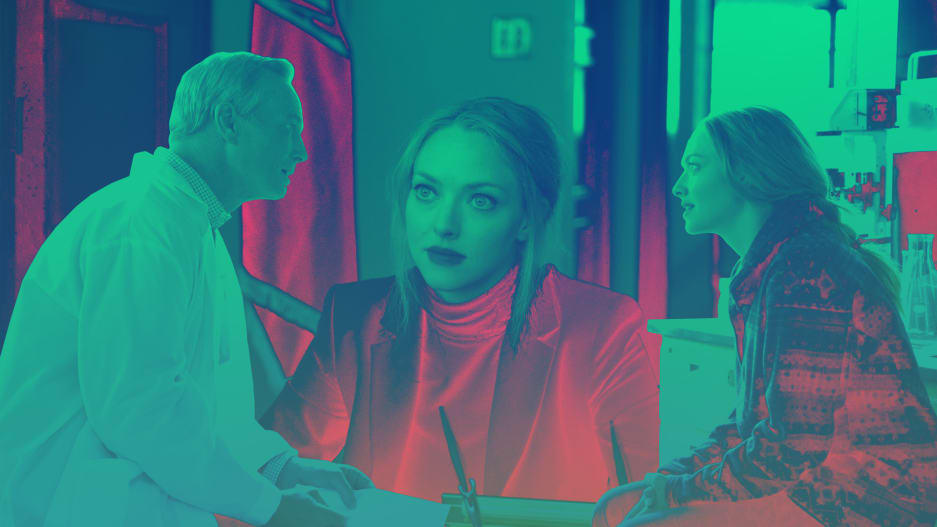

Hulu’s limited series ‘The Dropout’ retells the dramatic rise and crash of Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes—with a few dance breaks thrown in.

TV writer and showrunner Liz Meriwether (New Girl, Single Parents) hit two speed bumps when creating Hulu’s limited series The Dropout: One, she’d never worked with source material ripped from the headlines of a true story, and two, that true story belonged to Elizabeth Holmes, the former CEO of biotech company Theranos, whose meteoric rise to being the youngest, female “self-made” billionaire matched her Icarian plummet to criminal fraud charges.

For Meriwether, the challenge wasn’t so much covering the 12-year scope of Holmes’s saga, but how to root Holmes in reality when so much of what the public has seen (and heard) of her has been enigmatic and, at times, downright farcical.

“I felt a responsibility to think about her as a human being,” Meriwether says. “I think it’s actually more challenging to engage with her as a human being and to think about how I connected with her and didn’t connect with her. I felt that was an important part of the story, because I noticed that people were tending to think of her as distant from them, as a satire, as just the voice and the turtleneck and not engaging with the ways that she’s one of us.”

The Dropout charts Holmes’s (Amanda Seyfried) ascension from a Stanford dropout to creating a device she purported could run a multitude of diagnostic tests from a single drop of blood. Investors, including Oracle co-founder Larry Ellison, flooded Theranos with millions, resulting in a $9 billion valuation. The company boasted heavyweights on its board such as Henry Kissinger and former secretary of state George Shultz. Holmes graced the covers of Fortune, Forbes, and Inc., hailing her as “the Next Steve Jobs” and a revolutionary in the healthcare industry.

The problem was that her blood-testing device never worked.

Even during Theranos’s purported heyday, there were red flags of inconsistent clinical trials which led to to major deals with Safeway and Walgreens falling through. On top of that, there were whispers of a highly secretive and outright toxic work environment engendered by the steely-eyed CEO with a baritone voice, the authenticity of which was also called into question and eventually proved to be a fake. A deep investigation from The Wall Street Journal led to a federal investigation and the eventual demise of the company.

It’s the kind of Silicon Valley drama that Hollywood has been agog over.

There was the 2019 documentary The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley; there’s an upcoming film adaptation of John Carreyrou’s book Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup; and Meriwether’s limited series is based on a 2019 ABC podcast.

“There’s really amazing reporting about her. But because it’s reporting, it has to tell the story in a particular way,” Meriwether says. “But I felt like what I could do with a limited series was to try to understand the character’s points of view as much as possible, or at least present versions of them.”

Of course, Meriwether didn’t interview Holmes to develop the version of her that Seyfried portrays. So she was left blowing out even the smallest details from the accounts of people who knew Holmes.

For example, in The Dropout podcast, Ana Arriola, a former Apple product manger turned short-lived Theranos employee, recalled seeing Holmes dancing to a hip-hop song in her car thinking no one was watching. That idea of Holmes busting a painfully awkward groove plays out throughout The Dropout as a coping mechanism. Whenever she’s hit with some tough news—her dad being laid off from Enron, weathering an onslaught of rejections from VCs while getting Theranos off the ground, and so forth—Holmes leaves it all on the dance floor in her head.

“I don’t know what she was in like in real life. But I feel like as a character, this is a character who was not great at expressing their emotions and doesn’t have a lot of outlets for big feelings,” Meriwether says. “That little detail grew in my mind as maybe dancing is the way that she gets these emotions out. Dancing is the thing that she does when nobody’s watching.”

Meriwether notes The Dropout is “very much not a documentary,” but she filled in the blanks that she felt were necessary to give viewers as grounded of a version of Holmes as she could.

[Photo: Beth Dubber/Hulu]

“I don’t know exactly what anybody was thinking, but I felt like I could try to tell the story from an emotional place, from [a place of] trying to understand the emotional logic of it, which I think adds to the story,” she says. “I think it’s interesting to struggle with the ways that we connect to the characters and also don’t.”“There’s so many places you can go for the facts,” she adds. “This is like, ‘Let’s imagine what this was.’”

What The Dropout was to Meriwether, which she hopes viewers will agree with, is a meaningful addition to the ongoing discourse around scientific truths and big tech. “It was interesting shooting [The Dropout] after everybody went through these really personal experiences with [COVID-19] testing devices and home testing. And also the idea that science has objective truths—that has been really challenged recently,” Meriwether says. “The conversation should be happening now, because a lot of reckoning that we’re all doing with these tech companies is affecting policy and affecting personal decisions that we all make with tech and healthcare.”