One of SpaceX’s upcoming missions will send astronauts farther from Earth than they’ve traveled at any time since the early 1970s—with hopes of upgrading health care and communications for the rest of us stuck down here.

With Polaris Dawn, Isaacman and SpaceX have set their sights higher. Plans for this mission, set to launch no earlier than the fourth quarter of 2022 from the Kennedy Space Center using SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon spacecraft, include breaking an 853-mile altitude record for Earth orbit that’s stood for more than half a century and staging the first private spacewalk.

“This should be eye-opening about what can be achieved through private funding,” Isaacman said during a press call on Monday. He and SpaceX are each contributing to funding the effort, but he didn’t get into specifics about the budget.

But, Isaacman added, the point of the three-mission Polaris Program is not just to notch more firsts in non-government space travel, but to improve life on Earth.

Like Inspiration4, Polaris Dawn will double as a fundraising exercise for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital’s work in treating childhood cancer at no cost to the families involved. Isaacman wants to follow up on the $243 million Inspiration4 collected for that charity (including $125 million from he and his wife) by helping it to expand its efforts outside the U.S.

“They’ve done a fantastic job in the United States,” he said of St. Jude on the call after noting that the survival rate for childhood cancer drops dramatically in many other countries. “In other parts of the world, it looks a lot more like it did before St. Jude in the United States.”

Isaacman and his three crewmates on Polaris Dawn—pilot Scott Poteet, an Air Force veteran, and mission specialists Anna Menon and Sarah Gillis, both SpaceX engineers—will also launch with an extensive research agenda.

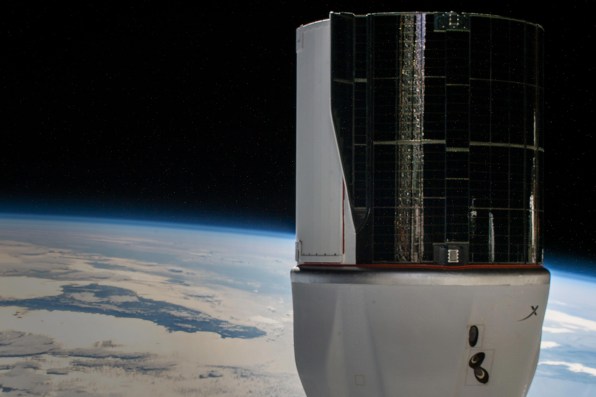

That work will include biomedical experiments as well as tests of the laser communications links on SpaceX’s latest crop of Starlink internet-access satellites.

[Photo: Space X]

Using that higher-capacity data-relay system may allow for more live video from the mission. But the real payback from these laser links will be to upgrade the still-growing Starlink constellation into an orbital mesh network that allows continuous broadband across oceans and over the poles.

Isaacman predicted on the call that telemedicine outside the U.S. could benefit greatly from expanded satellite bandwidth.

The unprecedented orbital altitude and space walk planned for Polaris Dawn also fit into a research agenda. Even getting close to the 853-mile apogee reached by NASA’s Gemini 11 in 1966 will subject the crew to more space radiation, a risk that must be managed for future long-duration missions far from Earth and will be tracked during this upcoming flight.

As for the “extravehicular activity,” it will involve an updated space suit designed for that instead of just being worn during launch and landing. That work should help SpaceX advance its suit design for other deep-space missions.

This EVA will take place as those on Gemini and Apollo missions did: Everyone onboard will secure loose items and suit up, the spacecraft hatch will open and depressurize the cabin, and some of the crew will exit the vehicle.

The second Polaris mission remains undefined, while the third will be the first crewed flight of SpaceX’s giant Starship rocket. That reusable vehicle, which will ascend atop a reusable Super Heavy booster rocket, remains in development, and nobody on the press call would venture a prediction about when the third flight might happen.

[Photo: SpaceX]

In November, SpaceX founder Elon Musk said that Starship’s first orbital flight might happen in January. But at a press conference last week at SpaceX’s Boca Chica, Texas, facility, Musk noted the difficulty of refining the design of Starship and Super Heavy’s Raptor 2 engines as well as delays in getting environmental approval from the Federal Aviation Administration for a launch from that coastal site.

“I feel, at this point, highly confident that we will get to orbit this year,” Musk predicted then.

Isaacman isn’t the only customer waiting for a Starship launch. As part of its long-delayed ambitions to return to the moon, NASA has picked SpaceX to build a version of that rocket to take astronauts from lunar orbit to the surface and back.

On the call, Isaacman voiced confidence in SpaceX’s ability to deliver upgraded space suits in the short term and an operational Starship in the longer term: “This is an organization that makes things that we never could have imagined.”

He also reiterated his hope that the achievements of the Polaris flights will be easily visible on Earth.

“We can make progress in space for tomorrow,” he said. “We can do that without ignoring some of the real challenges and hardships that we have on Earth today.”