- | 8:00 am

How Y Combinator, champion of ‘little tech,’ became the biggest machine in Silicon Valley

Under CEO Garry Tan, the startup factory is flexing the power of its network like never before.

With one week until the January kickoff of Y Combinator’s winter 2024 startup batch, there’s a hush in the prestigious accelerator program’s cavernous new San Francisco headquarters.

The only sound, aside from steady rain streaking the windows, is the muffled labor of two YC partners in a makeshift subterranean kitchen, where they are practicing a chicken and dumplings recipe to serve to a group of incoming founders. Like thousands of hopefuls before them, these founders will have 12 weeks to sprint toward product-market fit and notch the kind of growth metrics that wow investors on Demo Day, laying the foundation for unicorn status and possible Silicon Valley glory—no pressure. The gentle aroma of garlic drifts upward.

Garry Tan, a YC alum (summer 2008) who was named president and CEO just over a year ago, enters a glass-enclosed meeting room at one end of the banquet hall–size space, a former shipyard powerhouse. On X, formerly known as Twitter, Tan is known for his swaggering techno-optimism and sharp-elbowed politics (San Francisco’s lefty establishment is a frequent target). But in person, his voice invokes ASMR vibes. Only the latent energy in his posture, as he sits forward in his seat, hints at the intensity of his online persona.

Tan traveled to Taiwan over the holidays, but he didn’t exactly escape the YC community. “It turns out everyone was in Taipei,” he says, mentioning that he ran into Coinbase cofounder and CEO Brian Armstrong “in a $5 noodle shop.” (Tan’s $300,000 investment in Coinbase, a 2012 YC participant that he personally backed through his venture firm, Initialized, was worth $2.4 billion at the time of Coinbase’s public listing in 2021, an estimated 6,000 times return.)

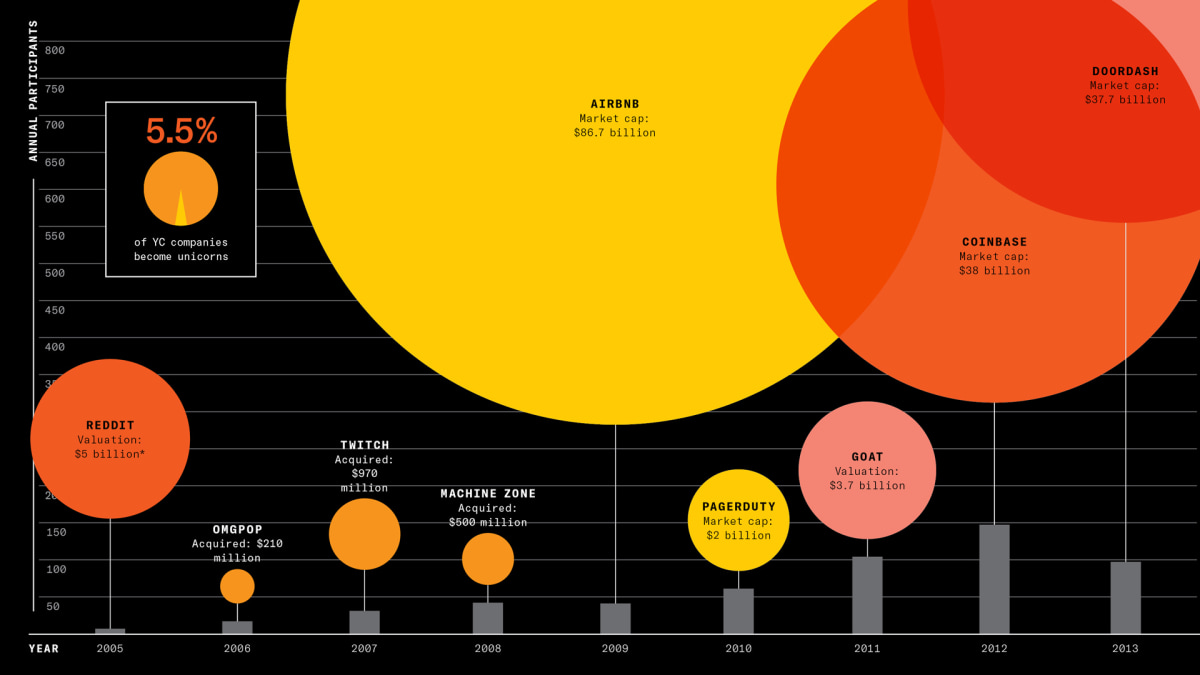

Look around San Francisco these days, and YC’s community of startup founders, now 10,000 strong, is just as ubiquitous. YC companies dominate current unicorn rankings (Stripe, Faire, Brex, Rippling) and lead IPO classes (Airbnb, DoorDash, Dropbox, Instacart). The city’s buzziest startup, OpenAI, is led by boy wonder turned Davos man Sam Altman, who dropped out of Stanford to participate in the first-ever YC batch in 2005, became a protégé of YC founder Paul Graham, and served as president of the accelerator from 2014 to 2019. Last fall, when Altman was briefly ousted from OpenAI (which went through YC in winter 2016), its board chose an-other YC mainstay, former Twitch CEO Emmett Shear, to serve as its interim leader. At the same time, Brian Chesky, cofounder and CEO of Airbnb (winter 2009), was publicly and privately rallying support for Altman, along with dozens of other YC founders. Within days, the YC network had helped reinstate Altman as OpenAI CEO.

That moment should have served as a signal that YC had arguably become the most powerful force in tech. YC touts that 5.5% of the startups that have participated in it have become unicorns, a rate at least double that of rival accelerators like TechStars and 500 Global. In aggregate, the companies YC has graduated are worth more than $600 billion.

Graham’s dream of creating a “replacement for the traditional corporation” has undeniably worked: Admission to the program doubles as a ticket to turning “building” into a career and “founder” into a profession. Who needs to work for a big company, Graham mused back in 2012, when the YC network functions like a less soul-crushing version of one?

When Tan took over in January 2023, though, YC was suffering from exactly the kind of corporate bloat that Graham abhorred. Beginning with Altman’s leadership in 2014, YC had expanded into everything from later-stage funding to dramatically larger batch sizes, turning what had been a rather artisanal process of nurturing fledgling startups into a one-size-fits-all factory-production model. A glut of venture dollars kept the production line humming . . . until that money stopped abruptly in 2022. Higher interest rates led to dramatic declines in VC dealmaking and private-market valuations, putting startups under more pressure to show early traction and revenue—or die.

Upon taking over, Tan made clear that he intended to reclaim YC’s roots and focus on serving early-stage founders, and his moves have been dramatic. He’s cut batch size from its 2022 peak, from 403 startups two years ago to 261 today. He’s also reconfiguring the organization so that its group partners, who oversee admissions and mentorship, own the founder relationships over the life of each startup. “We want that group partner to be the person who’s the guide, sort of the shepherd and the bodhisattva,” he says. “Literally, how do we help this company get to the promised land?”

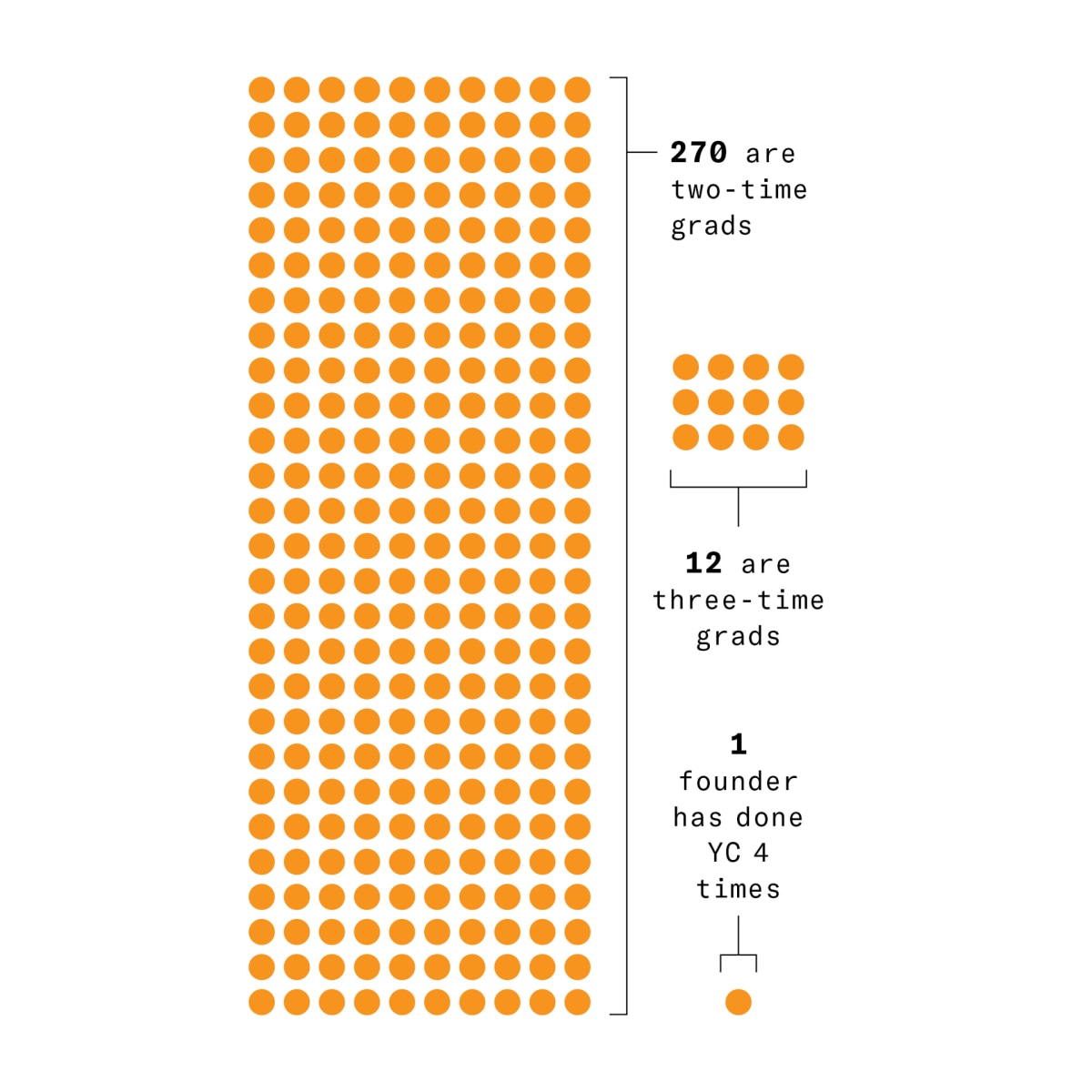

10,000 FOUNDERS have gone through YC. Of those who have returned . . .

Plus, somewhat controversially, Tan shuttered YC’s multibillion-dollar later-stage investment arm, axing its 17 employees just two months into his new role. “The big thing we’ve been trying to do,” he says, referring to himself and YC’s board of directors, which includes Graham, his wife and fellow founder Jessica Livingston, and Chesky, “is turn YC into that 100-year institution. In the end, what we figured out was that it’s too hard to do two totally different things and that what made YC has always been that batch process.”

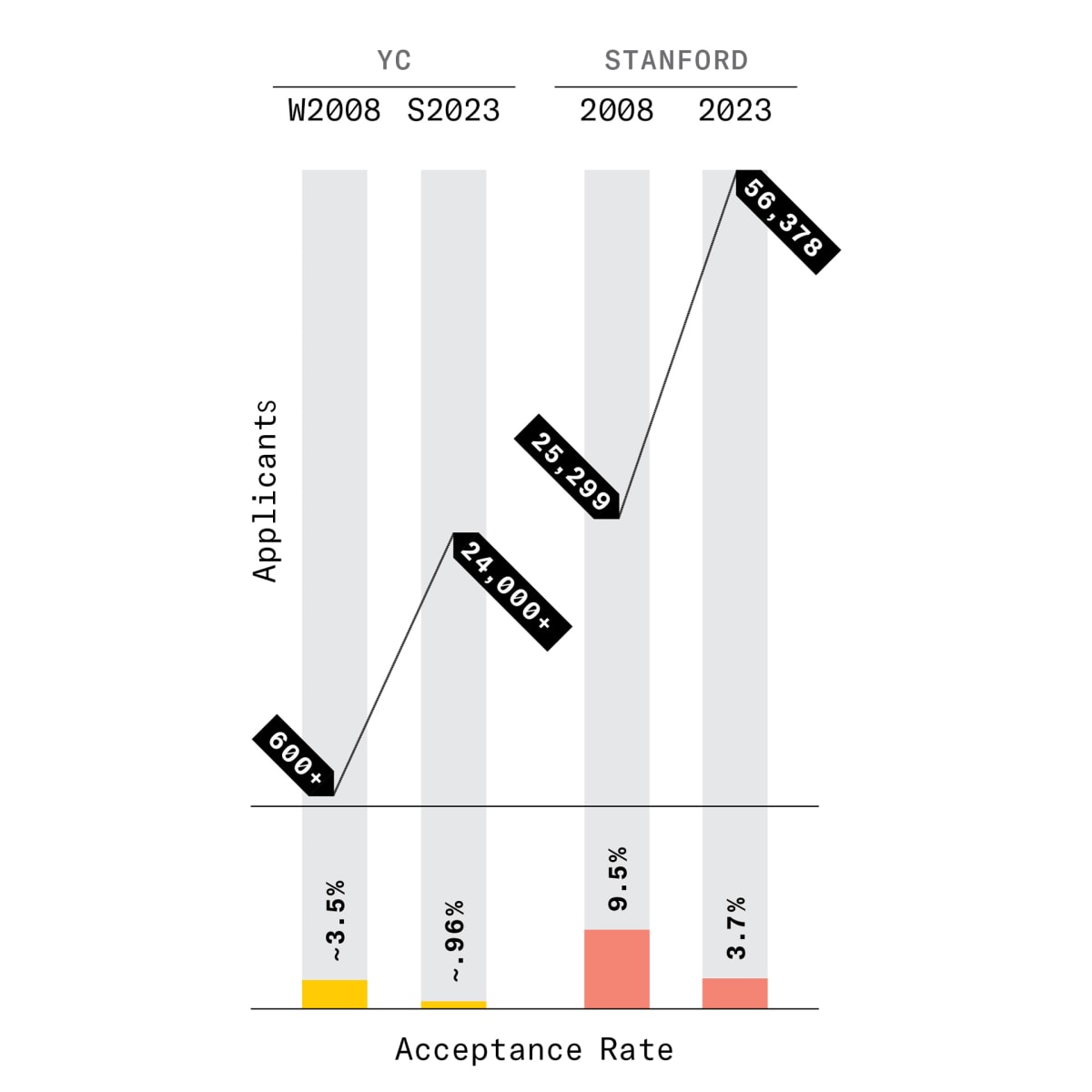

YC IS HARDER TO GET INTO THAN STANFORD

But if Tan is making a prudent tactical retreat from what he describes as Silicon Valley’s “foie gras” era, it would be wrong to assume that YC’s ambitions have been tempered. “I’d love for YC if 25% or 50% of the companies became unicorns—like, that would be crazy,” he says. “But then, if you think about the value of the community, the community actually becomes even more valuable to one another once that’s true.”

Of course, what looks like wealth creation from within the machine can look like power consolidation from the outside. Graham essays dating back to 2006 herald “the power of the marginal” and the valor of the outsider. YC still embraces this idea. But as the program under Tan expands into new spheres of influence, including the halls of power in Washington, D.C., a gap is growing between savvy branding and hard-knuckled reality. Just ask anyone who dares to stand in Tan’s way.

The story of YC’s rise and the story of the rise of founders in Silicon Valley are so deeply intertwined that they are effectively one and the same. In the beginning, YC was simply a voice in the wilderness, transmitted via Graham’s blog posts and public speaking. The first iteration of the program was little more than three months of improvised mentorship and community, plus enough money to cover basic expenses. (YC paid $6,000 per founder in exchange for about 7% equity.) VCs had historically served entrepreneurs predatory term sheets and ousted founders from their companies. Graham and Livingston served them chili every Tuesday night. “I just remember a feeling of being at home there,” says Daniel Rhodes (summer 2008), who founded a video startup that riffed on YouTube’s popularity and went on to work for YC companies Heyzap (winter 2009) and Atrium (winter 2018), a common path for alumni who make use of YC’s network and hiring tools.

“YC thinks about itself as an educational institution that happens to make money—but if I’m being economic, it’s also a marketplace,” says Twitch cofounder Justin Kan, who has taken four different startups through YC (a record) and also served for three years as a partner. In his view, YC’s ability to convene both best-in-class founders and investors is the key to the pro-gram’s staying power. “You can read all this stuff [about entrepreneurship] and just do it your-self if you want,” he says, referring to resources like Graham’s essays. But he notes that the “bundle” is a far better purchase: “You get the education, the network, and the access to a marketplace of investors.”

For founders going through the program, those three components are often indistinguishable. Christina Cacioppo, cofounder and CEO of security and compliance platform Vanta (winter 2018) and a former analyst at the powerful New York–based VC Union Square Ventures, dis-covered that alumni were not just willing to take her sales calls, they offered feedback, too.

“I remember cold-emailing founders—companies that were doing well, they had much better things to do—and they would actually reply,” Cacioppo says, “and sometimes it was like, ‘Hey, I think I know what you’re trying to say in this email. This email was bad.’ ” Another founder suggested she lead with a product demo when introducing Vanta.

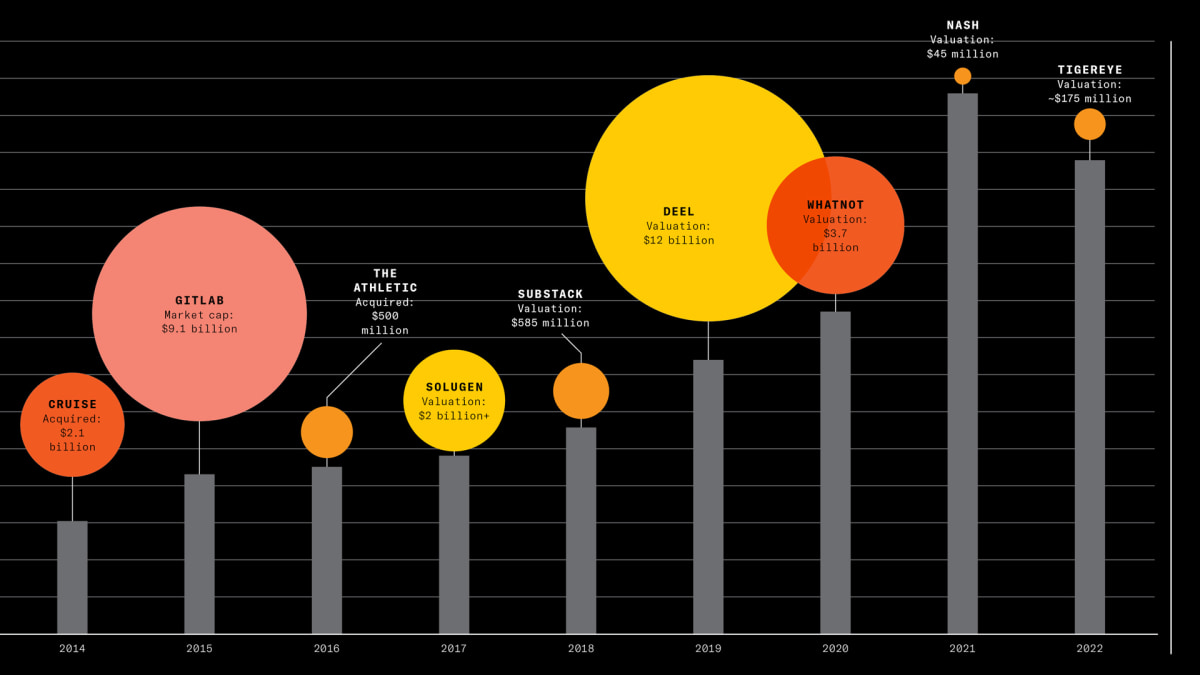

The Unicorn Breeder

Those learnings paid off. Last year, three-quarters of YC batch companies became Vanta customers; Vanta features fellow YC alumni Bend (summer 2022) and Belvo (winter 2020) as case studies on its website. Vanta’s angel backers include former YC CEO Geoff Ralston and YC managing director and group partner Jared Friedman (summer 2006).

YC famously tells founders to “make something people want,” but it also goes a step further, providing them with a receptive audience for that special “something.” The most successful example of this strategy is payments platform Stripe (summer 2009), which recruited early adopters from its YC peer group. Others include Gusto (winter 2012) and Rippling (winter 2017) with their payroll and benefits solutions, and Brex (winter 2017) with its corporate credit cards. (YC’s captive audience doesn’t guarantee success: Atrium, Kan’s fourth YC company, which offered startups tech-enabled legal services, failed with the approach.)

The benefits can accrue well after graduation. Serial founder Immad Akhund participated in YC as part of the winter 2009 batch as cofounder of Heyzap, a mobile gaming startup that was acquired for $45 million in 2016 by an advertising company. Starting in 2017, he spent two years developing Mercury, a banking service for technology companies that has become popular, as intended, with YC startups. Approximately half of every YC batch becomes a Mercury customer.

Akhund is also an angel investor. He reckons that he’s backed some 300 startups, including at least 100 YC participants. Rippling and Rappi (winter 2016), the DoorDash of Latin America, are among his biggest wins thus far. “I’ve already invested in three of the companies in the [cur-rent] batch,” he says, “and I’ll probably end up doing three or four more.”

Every angel investment involves a wire transfer, and that has Akhund thinking about a version of Mercury for personal use. Perhaps not coincidentally, given that many YC founders moonlight as angels, personal banking is also Mercury’s most commonly requested feature on X.

Founders are increasingly able to get everything they need from within the machine. A clubby online social platform called Bookface serves as the YC community’s digital hub. On it, veteran founders trade tips about which law firms to hire and which companies are subletting office space, while newbies try to drum up sales and investor intros. (YC also runs Hacker News, a Reddit-style public message board; Bookface is private, just for VIPs.) Founder Rob Hunter, a serial entrepreneur who once ran a chain of marble-slab ice cream shops in Canada, entered YC with HigherMe (winter 2015), a hiring tool for restaurants. In 2020, Hunter responded to a Bookface post by a former YC founder seeking acquisition targets, then sold HigherMe to the founder for an eight-figure exit.

Now, he’s turning to Bookface for his next project: a private-equity holding company dedicated to buying YC companies that aren’t growing fast enough to attract more venture capital. “The thesis is that these are great products started by founders who might not want to grind it out for the next three, four, or five years knowing that it’s not going to be a unicorn anymore,” he says. After acquiring these targets, Hunter plans to recruit CEOs from—where else?—within the YC family.

Bookface’s original builder is none other than Tan. Not content simply to dispense advice while serving as a partner from 2010 to 2015, Tan wrote the code for Bookface v1.0 (the name references a Facebook joke in an episode of The Office). At the time, batch sizes had jumped from a couple dozen startups to nearly a hundred, and founders were struggling to recognize their peers. Tan’s now hiring two engineers to focus on the product full-time.

For Tan, giving his life to startups required an almost religious conversion. Raised by immigrant parents, Tan took a job at Microsoft after graduating from Stanford in 2003. He was making $72,000; he bought a new Honda Accord. “I got the nicest leased apartment that I could get in the fancy part of Seattle so I could go drink martinis with my friends on Friday and Saturday nights,” he told Livingston last year during a guest appearance on her podcast. “I re-gret all that, because in the background, I knew that I wanted to start a company, but I sort of fell for the trap.”

Tan didn’t stay corporate for long. Stanford friends recruited him to Palantir, where he became employee No. 10, writing complex software that earned him several patents and even designing its logo. He later struck out on his own with Posterous, a blogging platform that stream-lined posting. Posterous participated in YC’s summer 2008 batch, and Tan has been a central figure in the community ever since. Many of the earliest photos of YC—Graham in his signature polo shirt and cargo shorts, surrounded by baby-faced nerds—were taken by Tan. In 2012, he joined two other YC veterans, Alexis Ohanian (summer 2005) and Harj Taggar (winter 2007), to launch a venture firm, Initialized Capital. Initialized’s portfolio includes 27 unicorns; 20 of them went through YC. When Tan affectionately describes YC as a “community that creates more prosperity,” the description certainly applies to his own wealth and career.

“It’s sort of like the Hair Club for Men,” he says, half-jokingly, when asked why it’s the right moment for him to be leading the organization. “You know, I’m not only the president. I also am a client.”

Despite those bona fides, his term as YC’s president and CEO started with a rare instance of public dissent within the network. When Tan closed YC’s growth-stage operation in March 2023, it still had more than $500 million in its arsenal, according to a person familiar with the matter. (YC disputes this number.) He also fired the partners who held board seats at a num-ber of the fund’s portfolio companies, and those affected were blindsided by the change. “Nothing about that decision was easy,” says Tan.

A reported 10 companies wrote a letter saying that they were “deeply disappointed,” including Brex, one of YC’s standout investments. “The way we heard about it was not the best,” says Brex cofounder and co-CEO Pedro Franceschi. Founders with the departing partners on their board requested that the partners be permitted to keep their seats, as is common when funds wind down operations. Tan, despite his experience running a venture firm, had seemingly not anticipated such a request. At Brex, former fund partner Anu Hariharan remains on the board as an observer.

While Tan sees himself as an evangelist for starting a company—“There’s just way more people in the world who could be founders who get locked up in certain life paths,” he says—he can sometimes punch down in a way that suggests what he really cares about is doing things his way. In September, Tan caught wind of public remarks by the head of another startup incubator, Neo’s CEO Ali Partovi, in which he compared YC’s founder-to-mentor ratio unfavorably to Neo’s. Tan blasted out a series of tweets: “Competition is good. What isn’t OK is when competitors like Neo slander Y Combinator by saying ‘YC does not offer personalized advice,’ ” he wrote. “Neo likes to parade their part time spekers [sic] as ‘mentors’ but will they be there 5 years in when you need office hours or help?” When asked for comment, Partovi replies, “Neo is the small, selective program for top technical talent that YC once was. YC is still an awe-some firm that serves thousands of aspiring founders, and is an especially good deal for inter-national teams with less access to capital.”

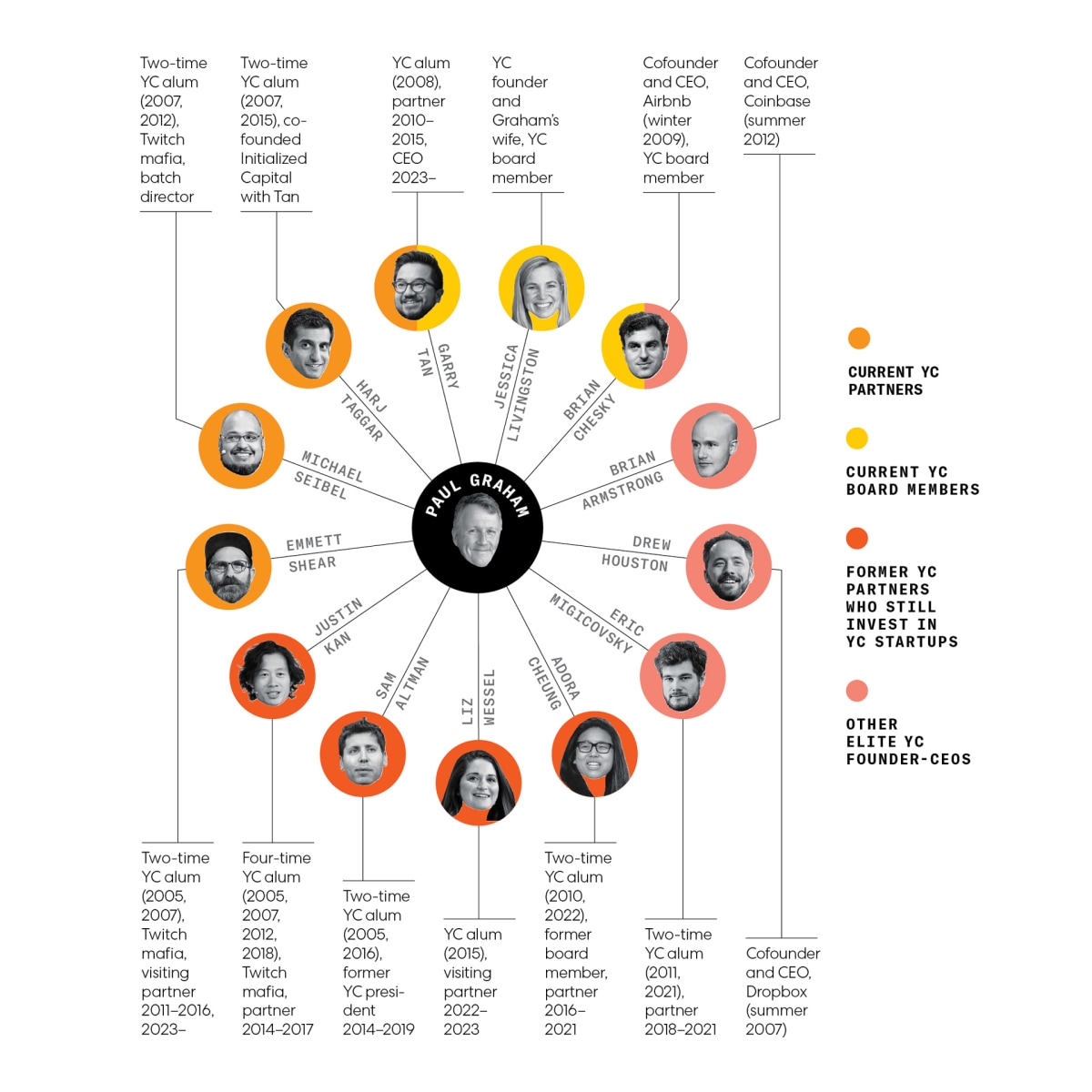

PG-13: A baker’s dozen of Y Combinator power players from the network founded by Paul Graham

Clockwise from top: Getty Images: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg; Dustin Chambers/Bloomberg; Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg; Martina Albertazzi/Bloomberg; Liz Hafalia/San Francisco Chronicle; Anthony Harvey/TechCrunch; Kimberly White/TechCrunch; Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg; Kimberly White/TechCrunch; Robin L Marshall; Kimberly White/TechCrunch; Kimberly White/TechCrunch; Philip Pacheco/Bloomberg. Center: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg]

Tan’s targets have also broadened in step with his political awakening and YC’s move from Mountain View to San Francisco. “Why did Garry Tan, the new CEO of Y Combinator, block you on Twitter?” asked the San Francisco Examiner after techies started to circulate evidence of being restricted from seeing his posts. The blocks were widely interpreted “as a sign that he wants to send a signal to founders looking to raise from his firm that they’d do well to support his political views or stay quiet on social media,” as one Hacker News poster put it. Lindsay Amos, Y Combinator senior director of communications, says Tan’s practices on social media are no different from those of other people with large followings. “He blocks abusive, inappropriate, or hateful comments,” she says. “Blocking should not be interpreted as a sign that founders need to have the same political views as anyone at YC. This sentiment is completely false.”

Like other prominent figures in Silicon Valley (see Marc Andreessen and his “Techno-Optimist Manifesto”), Tan has grown disenchanted with certain aspects of the liberal agenda. A self-described center-left Democrat, he has become deeply involved in efforts to address San Francisco’s interwoven crises—housing, drug addiction, and crime—through organizations like GrowSF, where he sits on the board along with his Posterous cofounder.

The version of San Francisco he wants founders to see is a “shining city of many hills,” as he says, and it’s why he’s waded into the recent successful recall campaigns of both school board members and the city’s progressive district attorney. Now he and other YC alums are backing favored candidates—including YC founder Bilal Mahmood (winter 2018)—to oppose the most left-leaning members of the city council.

While Altman and other alums have cheered on Tan and YC’s growing political activism, not every member of the community is a Tan-style tech accelerationist. “As a Black woman who was born in San Francisco—no, we’re not for all the tech dudes get-ting to be free and live their best lives in San Francisco,” says Phaedra Ellis-Lamkins, cofounder of Promise (winter 2018), a payment-processing platform for government agencies and utilities, who makes clear that she still feels a strong attachment to YC. “For us, technology is just a tool to improve the lives of people that we deeply care about.”

Members of the community who have known Tan for a long time appreciate what they describe as his authenticity. “He really wants everyone to succeed,” says Christopher Golda, who went through YC with Tan and, after the batch, crashed at his Mountain View rental. “The stuff he tweets, it’s not marketing.”

Though based on the Silicon Valley meme accounts that amplify Tan’s most aggressive pronouncements to young founders, his digital bravado is quite effective marketing. Late one night in January, Tan fired off a post directed at seven San Francisco supervisors, saying, “Die slow motherfuckers” and calling them out by name.

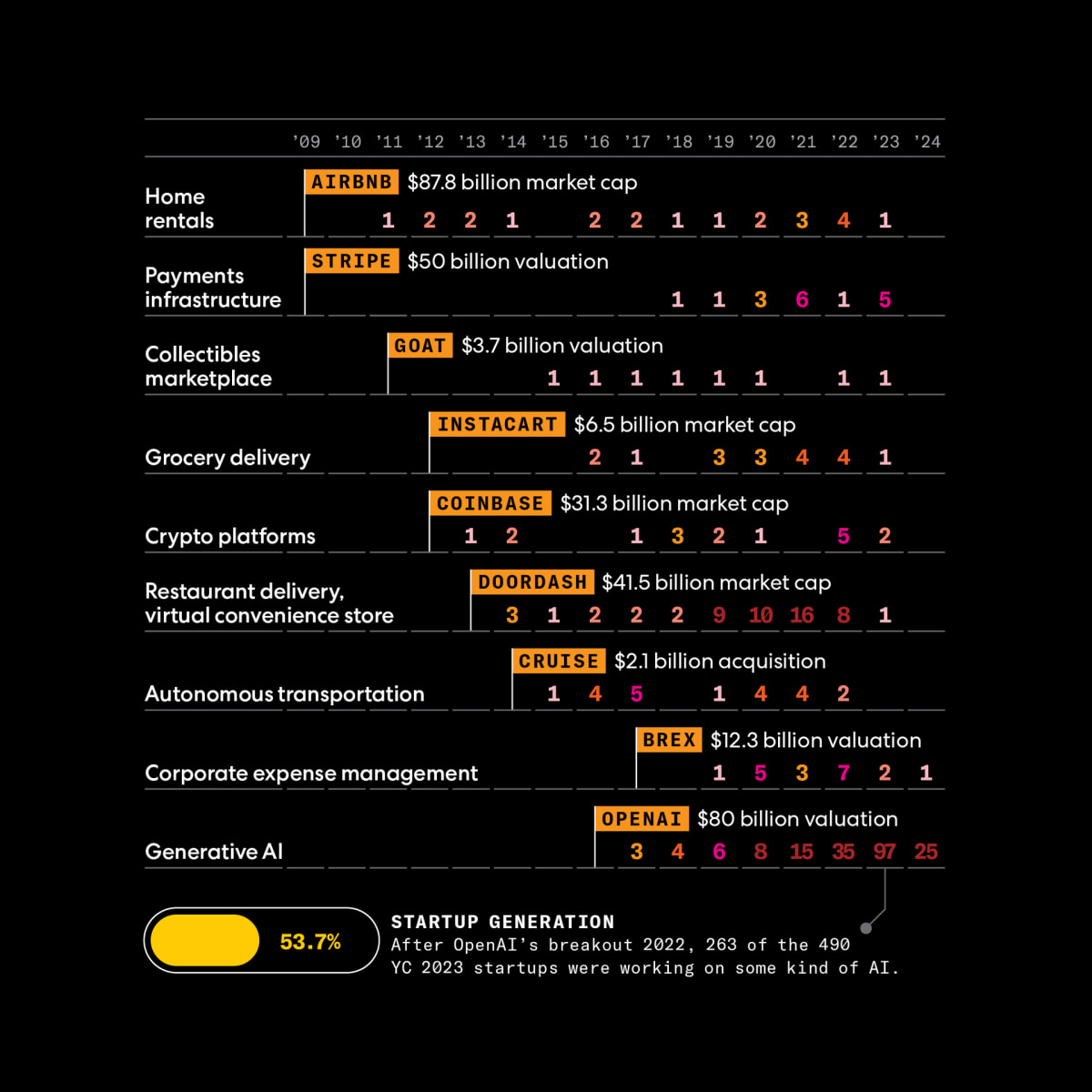

HEAT SEEKERS: When a Y Combinator company really achieves product-market fit, the accelerator has a propensity for backing similar or related startups for years to come.

A supportive follower thought Tan might be “hammered,” and Tan replied that he was. All in good fun, he seemed to imply, sharing a photo of his private liquor cabinet at San Francisco lounge the Lion’s Den. “Garry Tan ‘SF Social Media Troll Twitter Menace’” read the plaque below bottles of Balvanie and Macallan. Tan soon apologized, saying he was referencing the Tupac Shakur dis track “Die Slow.”

As Tan seeks to exert YC’s power in San Francisco, he’s also going national. He’s hired its first-ever head of public policy: Luther Lowe, who spent more than a decade at Yelp catalyzing a global campaign against Google and its anticompetitive practices. On Capitol Hill, Tan sees YC’s remit as advocating for “little tech.” Lowe has already used his new perch to fight on behalf of Beeper (summer 2021), a unified messaging app that challenges how Apple’s iMessage shuts out other services, and Tan invited FTC chairperson Lina Khan to speak to YC alumni last year, describing their conversation as “productive.”

“We’re ideally the antidote to big corporate interests controlling everything,” he says, sounding not unlike Big Tech leaders extolling all the small-business owners on their platforms.

Jason Kelly, cofounder and CEO of Ginkgo Bioworks, was YC’s somewhat reluctant first biotechnology recruit when the program opened its doors, at Altman’s behest, to hard technology startups in 2014. YC proved transformative for the synthetic biology company, which was founded in 2008.

“It taught us a tempo,” he says, echoing other founders and investors who laud YC’s ability to teach operational excellence. The MIT PhD also learned to fundraise. Before YC, Ginkgo had scrounged up less than $10 million in grants in six years; in March 2015, a year after graduating from the program, Ginkgo was ready to announce $9 million in Series A funding. By 2021, when the company went public, it had attracted $1.6 billion. “I could walk around Boston for years talking to everybody and not get $1 or I could go to 40 coffee meetings after YC and raise 5 million bucks,” says Kelly. “So, God bless the whole attitude of risk-taking and everything else: Ginkgo would not exist without it.”

YC’s move into hard tech proved that the program could successfully accelerate nearly any type of company, but these days, YC is agnostic rather than prescriptive about the types of companies it hopes to see apply. Over Blue Bottle coffee one morning in January, former Twitch CEO Shear smooths his beard and notes that he was “not a fan of crypto.” Yet YC funded a lot of crypto startups, including Tan’s life-changing bet on Coinbase. “And that was correct,” he says, “because that’s what the smart people wanted to work on at that time.”

Shear’s now a visiting partner at YC. If he had been in the role during crypto’s boom, he says, he would have happily set aside his personal misgivings. “The easiest way for YC to die is for YC to decide, ‘We know better, this whole crypto thing is a fad.’ And then it turns out—oops! It’s the future of the economy. That’s the mistake. The mistake is arrogance.”

This detached perspective has made space for YC to finance Silicon Valley’s wildest dreams, from brain freezing to nuclear fusion. It has also paved the way for startups dependent on contingent labor (every delivery app) or exploitation of the regulatory fringe (every crypto company, for starters). “I want YC to be a place where, regardless of ideology, people can thrive and create something people want,” says Tan.

Now, the smart people are apparently all working on artificial intelligence. Nearly half the cur-rent batch is utilizing AI, ranging from the practical (Konstructly: “Making construction payments more efficient”) to the mysterious (Artisan AI: “Creating the first human-like digital workers, called Artisans”). Tan’s strong pro-tech worldview evinces his belief that little should impede AI’s development.

The world they will graduate into on Demo Day looks strikingly different from the go-go days that have characterized most of YC’s history. On secondary trading platform Forge, private-market valuations were down 20% last year. Investor Aileen Lee, who coined the term “unicorn” in 2013, estimates that 60% of today’s 532 unicorns are “ZIRPicorns,” with inflated valuations from the froth of 2020 to 2022 and cash running out. High-flying logistics unicorn Convoy, which YC backed through its Continuity Fund, went bust in October last year. Many of the most valuable names in YC’s portfolio, from Stripe to Brex to logistics giant Flexport, are conducting layoffs or raising money at lower prices than in earlier rounds.

If there is one thing Tan is certain of, it’s that the unicorns of tomorrow will not look like the unicorns of yesterday. He muses about the possibility of an AI startup achieving unicorn status with just a handful of employees (Altman recently floated the possibility of a one-employee AI unicorn). Will such companies need YC? Next door to where we’re sitting, in Juul’s former headquarters, he’s setting up a video studio for YC’s popular YouTube content (Tan’s own channel has more than 250,000 subscribers). A new meeting room and café will host “Launch Bookface Live,” a weekly opportunity for founders to demo their progress with their peers. “The builder ethos is very important at YC,” Tan says. “As long as we’re around that and attracting those people, that’s all that sort of matters.”

Down the block, Gusto and satellite startup Astranis (winter 2016) share a building. In apartment towers nearby, founders from the current batch are living and working in 12-week Airbnbs. Across the city, shoppers for Instacart (summer 2012) and delivery drivers for Door-Dash (summer 2013) hurry to complete orders on the streets where autonomous vehicles from Cruise (winter 2014) once operated. No wonder Tan, a company man in a company town, looks at home.