- | 9:00 am

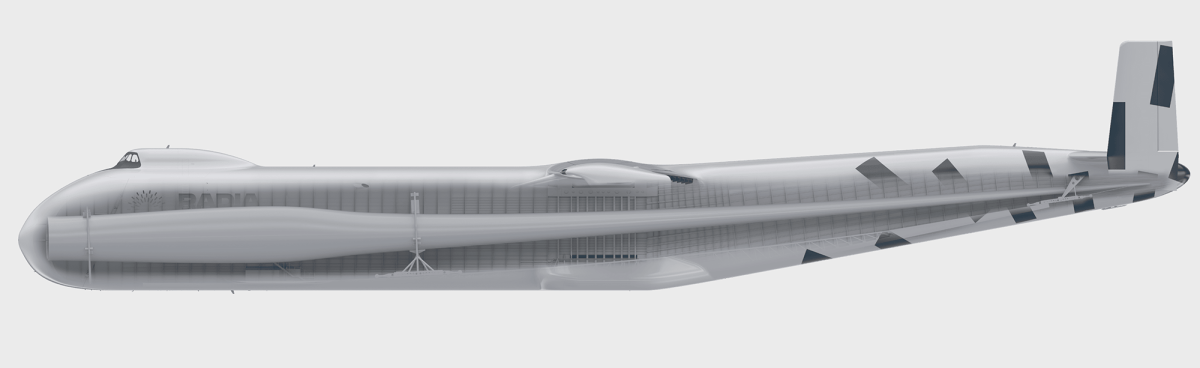

This will be the world’s largest plane—and it was designed to deliver just one thing

The Windrunner, from a startup called Radia, will be 356 feet long—enough to transport just one massive wind turbine blade at a time.

The bigger a wind turbine, the more energy it produces—which is why offshore wind farms have turbines with blades that are as long as a football field. But the largest equipment that exists today can’t be used on land because it’s too big to be delivered on roads.

A startup called Radia is working on one potential solution: The largest plane ever made, designed specifically to carry the biggest wind turbine blades to new wind farms while running on sustainable aviation fuel.

Using giant turbines can help shrink the cost of power. Beyond generating more energy because there’s more surface area, the taller height means that they access wind more consistently, so they run more of the time.

“The combination of those two things makes the grid more stable, energy prices lower, and it makes profits for the owners of the projects higher,” says Radia founder Mark Lundstrom. Jesse Jenkins, a Princeton professor who consulted for the company, calculated that a shift to the largest wind turbines could help bring down energy prices by 16%.

The startup, which launched in 2016 but just came out of stealth, now has a final design for the plane, Lundstrom says. As much as possible, it relies on standard components that are already in mass production. A scale model—1/42 of the final size—has been tested in a wind tunnel. The company is beginning to work with factories and suppliers to plan production; the team expects to begin commercial production by the end of 2027.

The plane, at 356 feet long, will have 12 times the volume of a 747. Still, the process won’t be particularly efficient: The largest blades are so enormous that the plane can only carry one at a time. The blades can be picked up from factories or ports; right now, manufacturers for the offshore wind industry have factories next to the water, so blades can be transported by ship. The plane can also deliver smaller blades that are still challenging to transport by road. (With blades that are a mere 70 feet long, it’s possible to fit four on the plane.) When it arrives at a wind farm, the plane is designed to land on a relatively short 6,000-foot dirt runway.

Other startups are working on different solutions, including one plan to 3D-print wind turbine blades directly at wind farms. Still, Lundstrom argues that manufacturing on-site would be challenging, and that it’s more economical to work with larger centralized factories.

Of course, it would be possible for new wind farms on land to keep using smaller turbines. But as the need for electricity quickly grows—both because of the shift to cleaner tech like EVs and because of new demand from artificial intelligence—using the largest possible turbines may be necessary to help supply enough power.

Radia already has a contract to deliver turbines to a gigawatt-sized wind farm. There isn’t a shortage of demand, Lundstrom says. “The amount of turbines that need to be deployed in the next 25 years to come anywhere close to the Paris goals probably is in the neighborhood of 6 million, 7 million blades,” he says. “Each of them is going on its own 1,000-kilometer journey from a factory to a farm. So there’s a pretty massive logistical challenge and opportunity.”