- | 8:00 am

Google and OpenAI’s announcements signal the end of the beginning of the AI wars

Two leaders in the AI wars announced chatbots this week that exploit the latest models’ multimodal and reasoning abilities.

Welcome to AI Decoded, Fast Company’s weekly newsletter that breaks down the most important news in the world of AI. You can sign up to receive this newsletter every week here.

THE GOOGLE AND OPENAI ANNOUNCEMENTS SHOW WE’RE IN A NEW PHASE OF THE AI WARS

Just last year, big tech companies were telling us how great it was that their large language models (LLMs) could summarize documents and write poems. Already the AI sales pitch has grown far more interesting. This week, the two leading players in the AI chatbot race, Google and OpenAI, demonstrated AI chatbots that tackle much heftier problems. So how exactly have the AI models that power these chatbots changed over the past year?

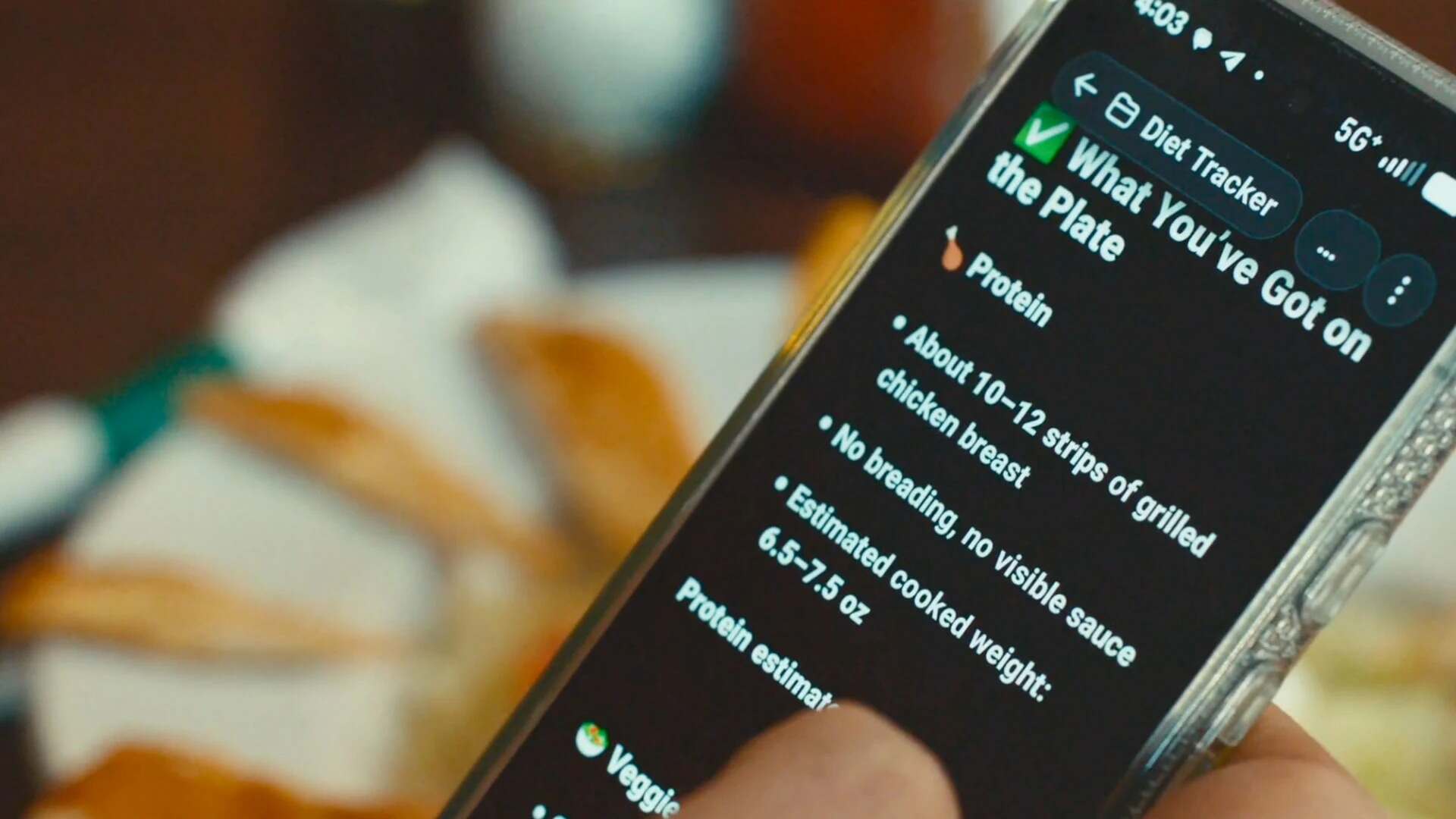

The leading models have become “multimodal.” They can understand and analyze not just text but audio, imagery, and computer code, and create answers in the same mediums. In a simple example, OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini can intake a visual image (perhaps through the camera of a smartphone) and describe in words the content of the image. “Multimodality radically expands the kind of questions we can ask and the answers we can get back,” Google CEO Sundar Pichai said at the company’s I/O event.

On Monday, OpenAI demonstrated an upgraded version of ChatGPT, powered by its new GPT-4o model (the “o” stands for “omni”). The most noticeable thing about the new ChatGPT is how “human” interactions with the chatbot feel. That’s mainly because of the sound and behavior of the ChatGPT’s Her-like speaking voice. Its tone is weirdly human; it sounds natural and expressive, even sultry and a bit flirty in some contexts. It makes jokes. It immediately stops talking when it hears the user start talking. The audio voice represents another “mode,” just like text or visual modes the model understands. And ChatGPT adds yet another mode—emotional intelligence, or “EQ.” It seems able to detect emotion in the user’s voice (in the demo Monday, the chatbot detected stress in the voice of an OpenAI researcher), and then affect its responses with appropriate emotion (for the researcher, empathy). Google will release a similar voice interaction chatbot called “Gemini Live” later this year.

More importantly, AI models have developed the ability to “reason” about these multimodal inputs. For example, Google demonstrated at I/O how its Gemini chatbot can help a user plan an upcoming trip. It starts by extracting the trip logistics (flights, hotels, etc.) from emailed reservations in the user’s Gmail; then, after gathering some information about the user’s interests, decides which activities might best fit within the available time, given their location (based on Google Maps data) relative to the user’s hotel.

In their respective demos, both ChatGPT and Gemini were shown math problems written on a white board and asked for help in working them out. Both companies demonstrated their chatbots reading computer code off a screen and analyzing it, for example. In fact, computer code may be the key to understanding how these AI models are now gaining the ability to reason and make judgments.

“When we trained the model with code, we learned that it got better at reasoning and math because code is a type of language that encodes logic,” said Sissie Hsiao, vice president at Google and general manager for Gemini, during an interview with Fast Company on Monday. “By teaching the model not just poetry, but things like code and other things that have structure and scientific reasoning inside them, it seems that what emerges is an ability to reason.”

It’s likely that we’ll look back at this week and recognize it as a time when consumer AI chatbots became more sensory, more reasonable, and even gained some emotional intelligence. Our AI helpers are still a work in progress but they’re clearly leaving their embryonic phase.

OPENAI COFOUNDER ILYA SUTSKEVER HAS LEFT THE BUILDING

OpenAI is the poster child for the current AI boom. It’s also seen ongoing drama around its executive ranks. Most recently, OpenAI cofounder Ilya Sutskever—someone who played a key role in ChatGPT’s blazing-fast ascent—announced he’d be leaving the company.

Sutskever is an idealist and a true believer that the benefits and control of AI should be widely distributed over lots of people—not concentrated in the hands of a few. He’s also deeply concerned about the societal risks AI poses and is cautious about exposing the technology in new products. Sutskever lost a power struggle to maintain those ideals within the everyday operations of the company. As the company took on more investment and began making a lot of money, forces led by Sam Altman (and the company’s backers, including Microsoft) made sure the company locked away its research advances from the rest of the AI community, and focused more of its time and effort on productizing and selling the fruits of the research.

This all came to a head last November when Sutskever led the OpenAI board to oust Altman. For one long weekend, Sutskever’s slow-and-safe approach to running OpenAI won out. But Atman soon returned. And Sutskever’s silence, or exile, or both, began. “Where’s Ilya” and “What did Ilya see?” became popular refrains on X (previouslyTwitter). And now, an important counterbalance to Altman’s aggressive approach to releasing new AI into the wild is gone.

DID INTERNET SEARCH JUST CATCH UP WITH (CHECKS NOTES . . . ) PERPLEXITY?

Maybe Gartner was right when it predicted that traditional web search volume will drop 25% by 2026. Over the past week, we saw the resurgence of rumors that OpenAI is about to launch an AI-native search engine. And, most importantly, we saw Google announce that its version of AI search will now be a regular part of its storied search service, which has been the dominant way of finding stuff on the web for decades.

All of this set the stage nicely for the publication of Fast Company’s in-depth feature on Perplexity, the AI startup that arguably beat everyone to the punch on AI-native search. It’s a story of how and why a small group of brilliant twentysomethings came to raise a challenge to Google’s decades-long stranglehold over the $300 billion search business.