- | 9:00 am

How tech’s biggest products get designed to exclude people of color

The new book Seen Yet Unseen makes a case that one size does not fit all, and sacrificing an entire group of people for profit while choosing to disregard them is even worse.

In addition to unionization for more humane working conditions, employees are on the front lines fighting for a say in how companies deploy their products and to whom to ensure they’re not being weaponized.

Big tech companies have seen more of this activism in the last few years, with protests regarding issues ranging from facial recognition products sold to governments to virtual reality products used to train soldiers to be more “effective” at their jobs. I’ll leave it to you to discern what that means.

It isn’t a coincidence that as the workforce gets younger and “woker,” corporate social responsibility and diversity are colliding. Per a 2016 Gallup survey, “Millennials struggle to find good jobs that engage them.” The bulk of this lack of engagement is due to not finding their work purposeful. This shift in generational workers also meant a shift in internal discussions in the workplace, dovetailing with the election of Trump.

After the 2016 election, a growing number of employees at companies like Facebook, Google, and Amazon began to change their thinking. When their CEOs seemed eager to kiss the rings and adjust for Trump, their employees began to actively speak up about their products being used for harm, particularly to marginalized communities. Companies pledged not to build databases identifying people by race, religion, or national origin. Keeping such promises, however, would require more than talking to one’s manager about surveillance or the security state.

In June 2020, Black Facebook employees staged a virtual walkout over lack of content moderation on the platform and the need for diversity in the leadership making those decisions. Zuckerberg has always had a public standpoint of being hands-off with regard to policing what people post, including then-President Trump.

So, much to the ire of Black employees, incendiary posts blasting the Black Lives Matter movement protests in the wake of the murder of George Floyd abounded. Trump’s post stating in part, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts” was the last straw, especially after Twitter applied a notice to his tweet, saying it violated terms of service regarding violence.

In response, Facebook employees circulated petitions and threatened to resign due to the lack of content moderation, and several wrote publicly about their unhappiness on Facebook, Twitter, Medium, and elsewhere. Employees described the ire as the most serious challenge to Zuckerberg’s leadership since the company’s founding.

According to Tech Crunch, “Zuckerberg responded to internal frustration and escalating clashes between protesters and police by announcing that Facebook would donate $10 million to groups fighting for racial justice in the United States.”

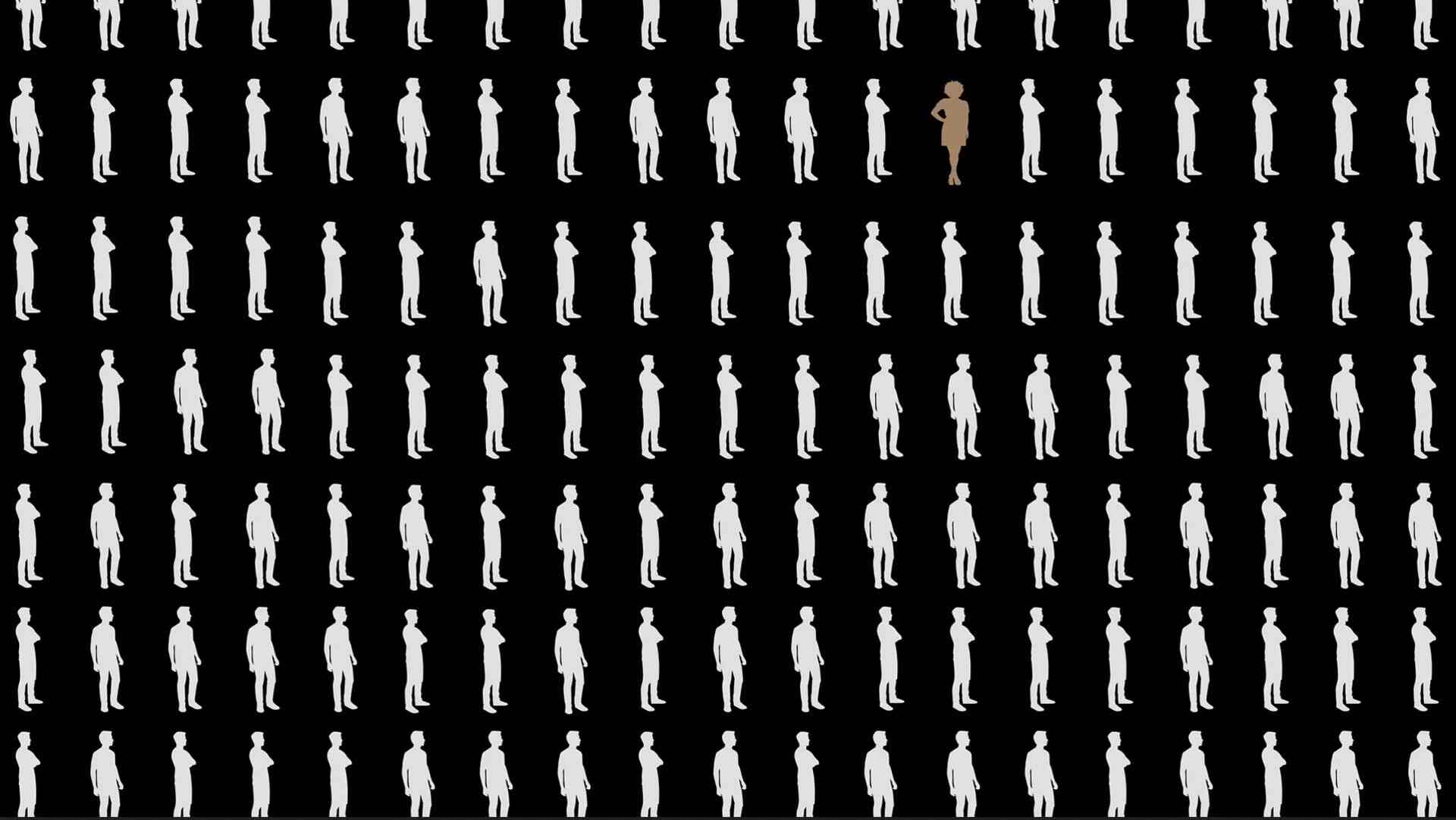

That amount seemed paltry for a company with a market capitalization of over $650 billion at the time. Also, throwing money at a social problem when hypocrisy abounds inside is perceived as disingenuous, at best. Hurting the general populace impacts the bottom line of big tech companies, and having Black women in the room during everything from product conception to content moderation would have saved them big dollars—and lawsuits.

Tech executive Annie Jean-Baptiste spoke about a teammate who summed this up perfectly: “If you’re talking about ‘them,’ there had better be some ‘theys’ in the room.” Without them your product is inherently flawed.

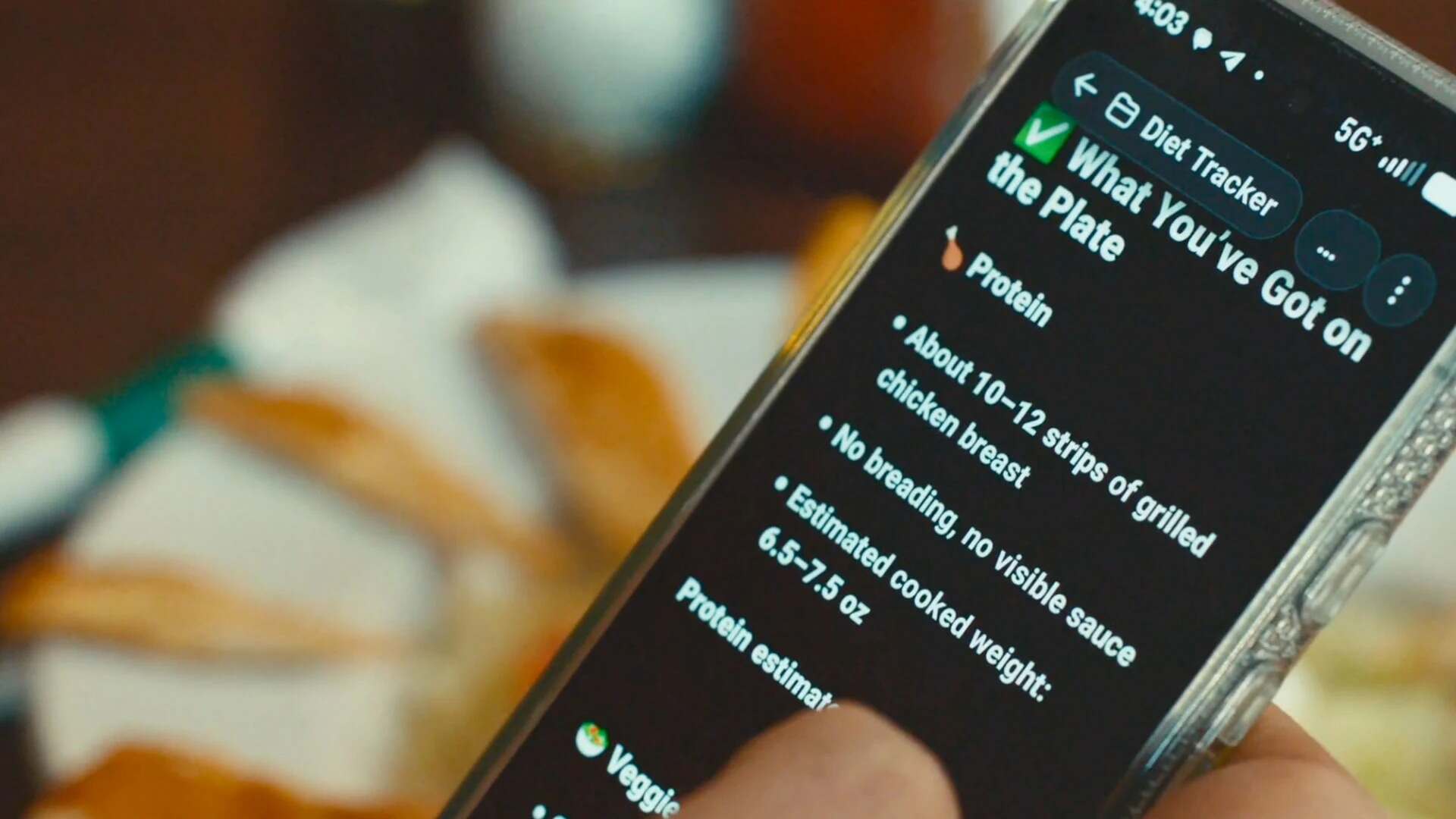

At the core of product creation, according to Jean-Baptiste, tech companies should consider who the “user could and should be. It’s not about completely doing away with the target customer or user you had initially focused on, but about widening the pool” of who that user could be.

There must be an acknowledgment that everyone has unconscious biases, which are born out of how we perceive and are perceived in the world because our minds use mental shortcuts for decision-making.

Acknowledging these biases and the fact that images of creators are not the same as the “average user” will shore up many of the blind spots that run amok in tech. Responsible creation requires asking, “I don’t represent everyone around the world, so how do I get those different perspectives in?” As Jean-Baptiste says, “I identify as a Black woman, but I don’t represent all Black women. So how do we make sure that one, we’re not pegging communities as a monolith and two, we’re getting those potentially historically marginalized perspectives into our product design and development process?”

Jean-Baptiste’s research has found that this process should have four essential inflection points: “ideation, user research and design, user testing, and marketing.” The problem with incorporating diversity is that diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) always centers the moral case: “It’s the right thing to do.”

We know that doesn’t appeal to companies; if it did, I wouldn’t be writing this book. Instead, the appeal should focus on the business and monetary aspect, which I know from personal experience can be a success. It all comes down to creating “a shift, from seeing these groups as underrepresented to having a ton of cultural and economic power.”

When I made the business case for supplier diversity at Facebook, I focused on the spending power of diverse groups and how they want to use products created with them in mind. Aside from the monetary aspect, there is also the new ROI: return on influence. Just as Black content creators are monetizing social media platforms and the companies that advertise on them, companies need to disabuse themselves of the notion that underrepresented means “powerless.” “Black and Latinx consumers . . . have trillions of dollars in purchasing power,” and women decide the bulk of household spending. Never mind the cultural cache of Black women who start and lead cultural trends, so ensuring that our needs, wants, and use cases are rooted in products is just smart business. Bring us in and bring us in early.

Advocacy starts from the inside and begins with who is sitting at the table. It includes implementing community-based participatory research in the discovery phase to allow the community to “lead at the outset, in terms of what their goals, needs, and challenges are, versus having them come in and provide perspective later in the process” or after the product has shipped.

We’ve seen how that goes. Now it’s time to be the advocate, and companies can start with three easy-to-implement solutions.

Be proactive about bringing all the voices to the table.

Ask yourself how often people from marginalized communities are in the room when decisions are made and hard questions are asked. Do the decision-makers listen, and then do they implement those ideas? Ideas are fantastic; execution is better. Also, please understand that one person is not a spokesperson for their entire race. We aren’t a monolith. Seriously. Having the stamp of approval from the chief diversity officer isn’t good enough, particularly when that person may also be fearful of dissent at the risk of losing their job. Making decisions shouldn’t be left to one “representative” but a collective.

Deliberately ask yourself how you can be an ally.

Be a Trojan horse. If you are in rooms where underrepresented voices have not been invited, find ways to advocate for them. When creating a product or looking to solve a problem, ask yourself if the solutions presented would work for them. An example of this in my own work is when I inquired about a new app that required the user to look at their phone to unlock it. I simply asked, “How does a blind person use this?” No one had an answer, and why would they? No one in the room was blind.

Carefully consider whether your product or new feature may have unintended negative consequences or can be used for nefarious purposes against marginalized people.

This is imperative if you are dealing with AI technology, which is used to determine creditworthiness, policing of communities, surveillance, and housing. If you aren’t sure what those negative impacts could be, test your products with people from different backgrounds and lived experiences and take their feedback seriously.

What’s stunning is the sheer number of tech transgressions we’ve seen in the past few years: misuse of private user data, subversion of democracy via voter suppression, spread of disinformation due to lack of content moderation, taking investments backed by foreign funds, and continued reluctance to amplify the voices of diverse content creators to address these blind spots.

The problem, as always, is having a homogeneous group of people in the room making decisions that affect the lives of heterogeneous populations around the globe. One size does not fit all, and sacrificing an entire group of people for profit while choosing to disregard them is even worse. In fact, being profitable and being principled is only as hard as business leaders make it. Being both can lead to greater profit.

Adapted and excerpted from Seen Yet Unseen by Bärí A. Williams. This excerpt was published with permission from the author and the publisher, Blackstone Publishing.