- | 8:00 am

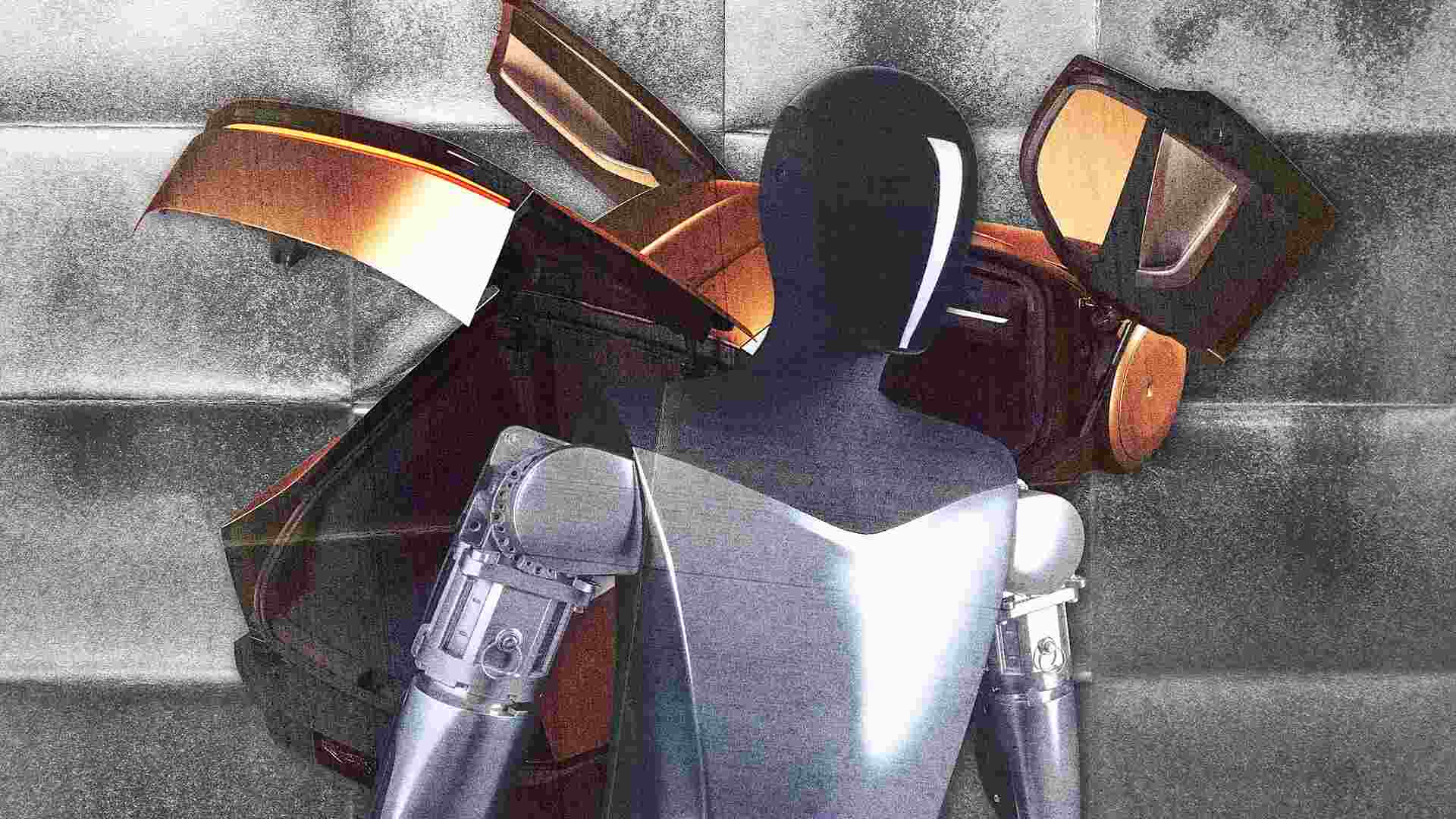

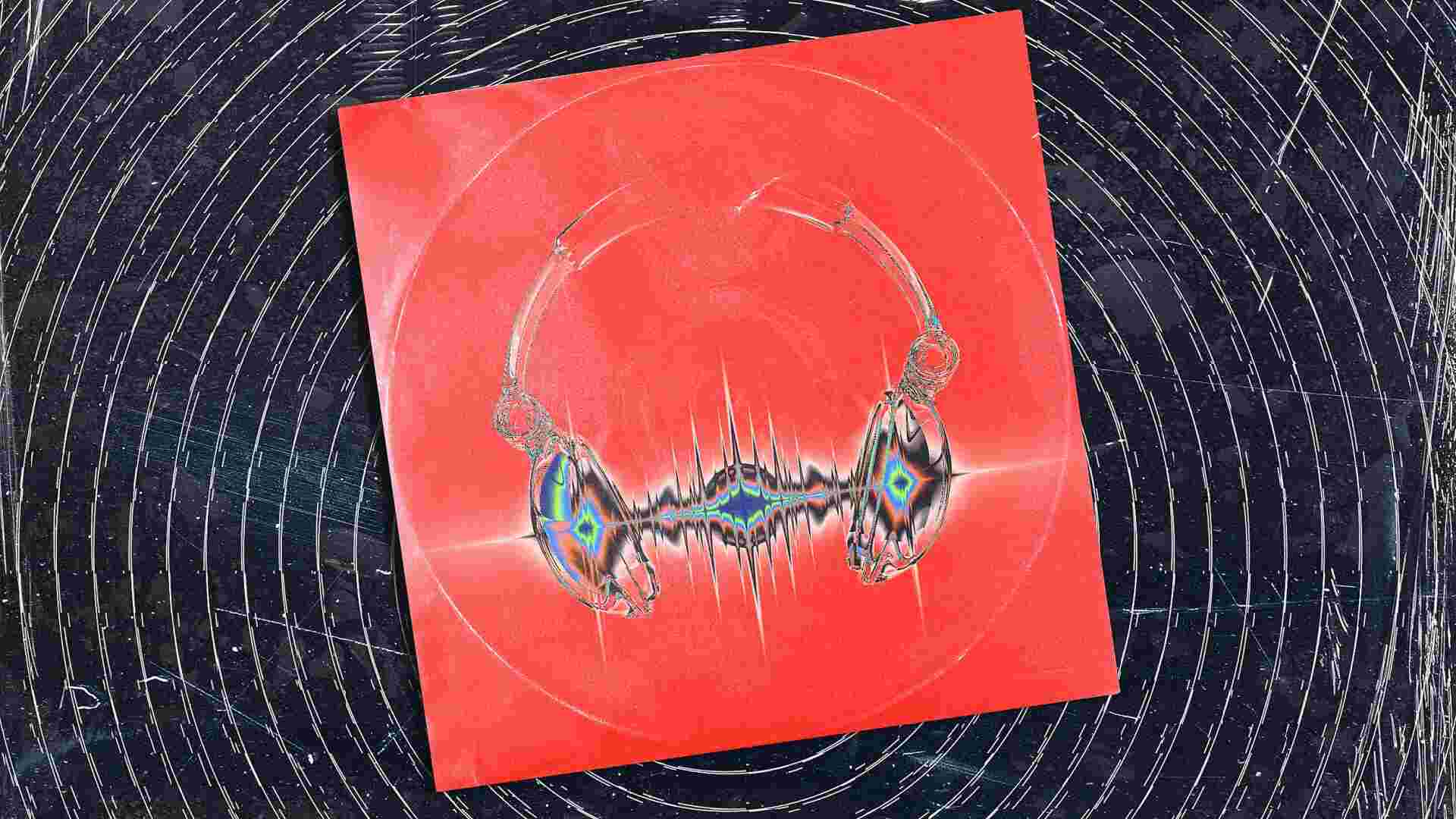

The AI revolution is coming for your headphones. Are you ready?

New technology is turning headphones into reality-editing machines that can reshape how you hear the world.

When Apple introduced the AirPod Pros in 2019, it planted the seed for an AI audio revolution. Using real-time, AI-powered sound processing technology, the AirPod Pros altered the way we listen to the world.

This wasn’t a matter of merely blocking out noise; Apple’s technology effectively reconstructed our sound reality into a synthetic version of the real world. This shift in how we hear the world was in some ways subtle: Now we could walk down the street and listen to our music while still being in tune with the world around us. In other ways, it was revolutionary: A feature called ”Conversation Boost“ used audio processing to amplify the sounds you like (ie. your friend’s voice), while canceling or reducing the level of everything else. With this new technology, Apple introduced people to the idea of using headphones to alter the way we listen to the world. This opened up an opportunity for other companies to take the AirPod Pros’ synthetic audio premise beyond our wildest sci-fi dreams.

Now, two groups of researchers are developing a new breed of AI-powered headphones that are taking AirPod Pro concept into overdrive. They want to reprocess our audio in ways we could have never imagined, selectively boosting, processing, and suppressing sound into a new, real-time auditive reality.

THE NEW REALITY IS GOING TO BE WILD, BUT FAKE

“Sound is such a fundamental medium through which we perceive our environment,” Seattle researcher Shyam Gollakota tells me in an email interview. “However, today we are surrounded by a cacophony of sounds that can end up overwhelming our senses. What we are doing is building intelligent hearable systems that can get back some choice in terms of what sounds we hear in real-world environments.”

Gollakota leads the mobile intelligence group at the University of Washington’s Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, where he and a team of researchers have been working on real-time augmentation of the human auditory perception for more than four years.

Their goal is to program what Gollakota calls “acoustic scenes in real time.” “When people talk about deep learning and AI, the most common thing is chat-based interfaces,” he says. “But what we set out to do is show that we can design real-time deep-learning methods that can program acoustic environments as well.”

In 2022, Gollakota’s team came up with a device called Clearbuds, which enables people to have clearer conversations during Zoom calls. In 2023, they developed Semantic hearing, a pair of headphones that allows people to pick the specific sounds they want to hear; for instance, amplifying the birds chirping in the park but blocking out the people chatting nearby. Then last month, they released something called target speech hearing, which lets headphone wearers choose a specific speaker in their environment to listen to just by looking at them, thus muting everything else.

“Imagine you and a friend are walking and chatting on a busy street,” Gollakota muses. “Wouldn’t it be great if you had a pair of headphones that [could] learn the voice characteristics of your friend and suppress street noise and the speech from passers by, so you can focus on what your friend is saying?”

THE SCIENCE BEHIND TARGETED LISTENING

To achieve this objective, Gollakota and his team developed a processing software with a high level of intelligence capable of simultaneously identifying all the different sounds and speakers in an environment. From there, the system needed to separate the target sounds from all the interfering noises. “If this is not hard enough, whatever sounds we extract need to sync with the user’s visual senses,” he says.

A lag between what people see and hear is disorienting, so the technology’s neural algorithms must process sounds in real time in under one-hundredth of a second. In the team’s research paper, his team demonstrated that they were able to make the neural network small enough to be embedded right on the headphones. This cuts the response time to the bare minimum so it can work in real time using very limited computational capability and battery life—something unattainable by current headphone technologies until they came along. “We do think that we are inventing and showing the path and feasibility of what kind of intelligence is indeed possible on these devices. We also make the code available for other researchers to work on it so this is real.”

A COMPUTER IN YOUR EAR

The Iyo One goes even further than UW’s device in augmenting your audio reality. Think of it as a display-less Humane Pin or Rabbit that lives in your ear and communicates exclusively through audio, taking your voice commands like a personal Enterprise computer, while also filtering your audio world. Externally, the stereo headphones look like big shiny flat circles that partially cover your ears. They get attached to your head, thanks to a soft body that goes into your ear canal, isolating you from the world like the AirPods Pro do. Inside this body, you can find all the electronics that handle the environmental audio and synthesize it into a new audio reality.

Jason Rugolo—the founder of Iyo—believes that audio is the future of computing interaction. “I came to Google X right when the transformer architecture was invented inside Google in late 2017,” Rugolo tells me via email. “I saw early that computers could soon speak natural language, and so became enamored with the idea that we’ll all be talking to computers all the time in the future.”

At Google X, his team explored many kinds of wearables: pins, broaches, necklaces, bracelets, clothing, glasses, hats, earbuds. They quickly realized that the natural language interface must live on the actual ear. This is because your voice pickup has to be very good (in the canal) and your audio “display” has to be private.

Rugolo says that his audio computing device will be able to do the same as the University of Washington invention and then some. In his recent TED 2024 talk, Rugolo demonstrated how Iyo One had the ability to filter specific sounds just by looking at the source or on command. Want to get rid of the lovely baby crying in row 35 of your flight from JFK to Tokyo? Just look at it and filter out the noise (sociopathic face optional).

“We’re super focused on delivering an enormous amount of value from day one,” Rugolo says. And he’s confident that there will be a lot of people who will want the Iyo One at a price point of $699 just for the audio features alone. He promises that his audio computer will also ship with apps to add value that none of the other pseudo-iPhone gadgets can offer with this level of privacy and interaction. “Real-time translation, hearing enhancement, natural-language search, and a conversational music app will all ship with our first device,” he says. The device will also open up for third-party developers to build apps at the same time, claiming that they already have developers “building some incredible stuff.”

Rugolo says they have had hundreds of people at work on this project over the past six years and they plan to ship Iyo One this winter, with preorders available now. “It will look exactly like the one I was wearing at TED, which was a prototype device . . . made of a titanium chassis with a glass sapphire front.” He says the device has all the same bits as a smartphone except for the screen plus a lot more microphones.

Gollakota, however, doesn’t dare propose a magical device that will replace a smartphone with an earbud device. “I think that is a very challenging task given smartphones are so ubiquitous and have a large number of functionalities and interaction modalities that are done extremely well,” he says. He’s more interested in reconstructing the audio reality around us, which he believes will be part of future headphones and earbuds in the next few years.

Gollakota has witnessed two key technological trends during the last decade that make this promise feel real. First, there have been significant advances in noise-canceling headsets and earbuds. Second, deep learning is enabling promising human-like intelligence. These two trends present opportunities for creating the future of intelligent hearables, Gollakota says, with real-world capabilities that so far have been in the realm of science fiction.

“We will start seeing intelligence in our headsets within the next five years, and I think this does not require replacing a smartphone,” he says.

THE SCARY FUTURE OF AUDIO

Both concepts sound fantastic, but controlling our audio environment has some potentially dark downsides. Right now, these speech-to-speech models run on the cloud but, in a couple of years or less, they will be living on-device, enabling apps that can change the voice of people around you—or your own voice—in real time. (And like any technology, bad actors can turn a magic experience into something scary.)

But despite potential pitfalls, Gollakota remains optimistic that synthesizing our audio reality is ultimately a good thing. “Right now, people can turn on their noise-canceling headsets and tune out everything. What my group is doing is giving back control to the users so they can let some of these ambient sounds and speakers come in,” he says.

His argument is that noise pollution is a well-being issue, and these devices could help. “Eventually, it is better for people to choose for themselves what they want to hear rather than a select few dictating what they can or can’t do,” he says.

Still, there’s a more profound philosophical question that is embedded in our very definition of what being human is. What does it mean for a fundamental part of ourselves to be adulterated? Is digitally altering our experience truly the route to change an annoyingly noisy world into a pleasant one?

Perhaps we should all strive to be more respectful to each other, to do what we would like others to do and make a better world around us. Maybe I’m naive, and we will never run out of gross people who chew and talk with their mouths full of food, babble incessantly in the quiet train car, leave or listen to voice messages on speaker phone in the bus, chat loudly in restaurants, or slurp their hot coffees. In which case, I guess I’m condemned to join the alternate audio reality world or move to a beach in Cádiz, Andalucía, and live like a monk. Looking at the state of things . . . somehow, the latter seems more and more attractive by the day.