- | 9:00 am

Welcome to the age of the AI-optimized building

Buildings and AI are both notoriously bad for the environment. Now they’re working together to reduce emissions.

As the climate toll of artificial intelligence becomes clearer, environmental analysts would tell you that a significant part of the problem is computing power. The vast web of data centers needed to train and run large-language models—and the construction emissions and energy needed to construct and run these buildings—creates significant carbon emissions.

But this reality comes with a complicated caveat, because other sectors of the built environment see AI as a vital part of reducing their emissions. As big buildings—and their energy, heating, and cooling systems in particular—become “smarter,” AI is paving the way for major leaps in building efficiency.

WHAT AI CAN DO

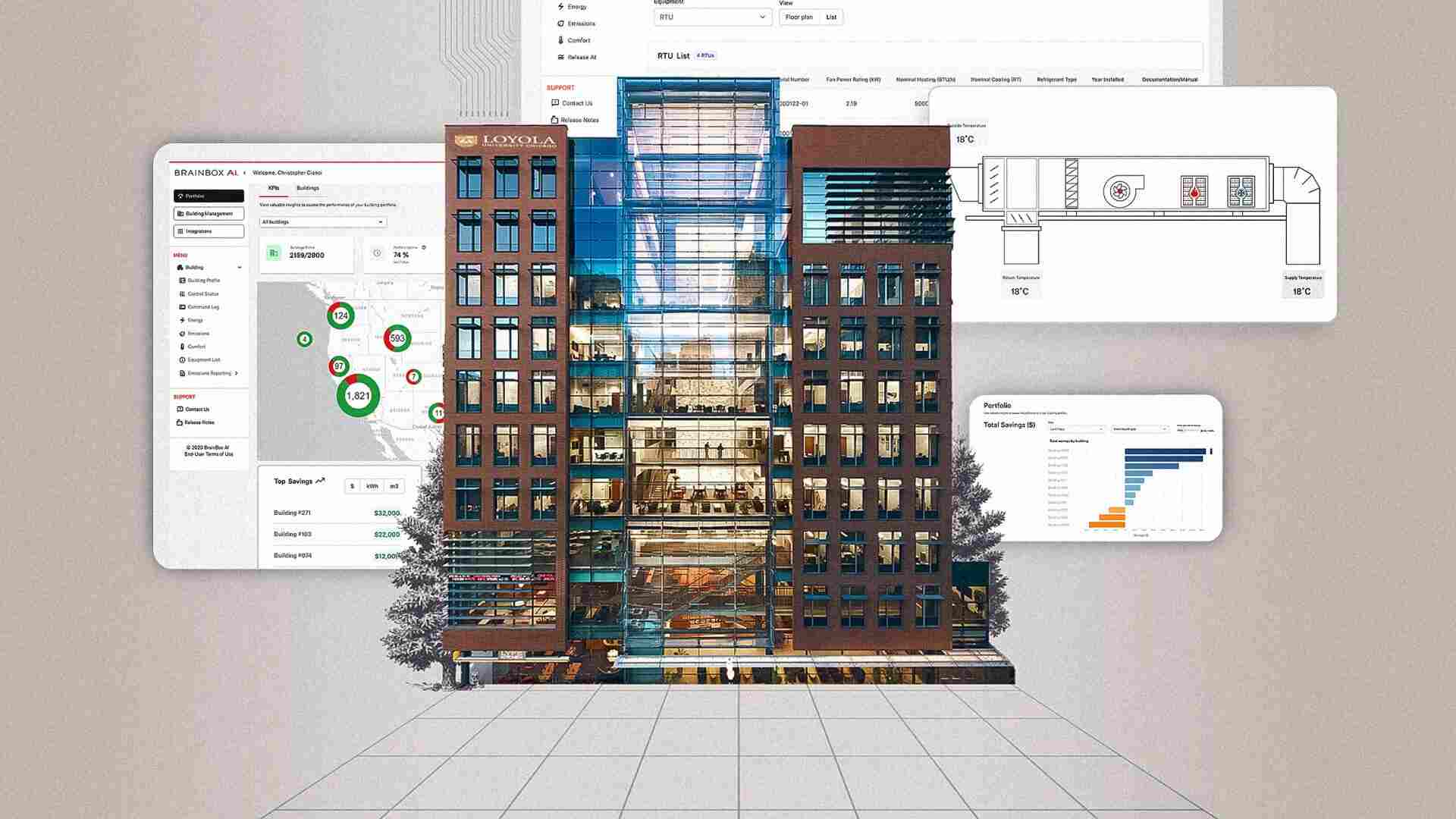

At the downtown campus of Loyola University in Chicago, a recent trial showcased why so many tech firms remain optimistic. The Schreiber Center, a 137,000-square-foot center for the business school that opened in 2018, boasted state-of-the-art sustainability features, earning it LEED Gold Status.

Then, beginning in 2022, it tried to best itself. The school installed software from Montreal-based startup BrainBox AI designed to automate the operations and heating, ventilation, and cooling (HVAC) system. The goal was to see how much more emissions could be reduced at an already high-performing building. Analysis of the yearlong trial showed that AI cut energy bills by 10% and reduced C02 emissions by 15%.

The built environment faces significant environmental challenges, from the ways buildings are powered to the material used in construction. But the widespread adoption of AI to moderate operations and make buildings more efficient offers a quick way to slash energy substantially during a decade when environmental goals demand quick action.

Firms like Measurabl, which monitors and analyzes energy and emissions data for 18 billion square feet of real estate, have grown their business in recent years. The Better Building Initiative, a program the Department of Energy started in 2011 to encourage investment in energy efficiency technology, has cumulatively saved $18.5 billion in energy bills.

A push for more investment comes as building owners and operators see going green as more than just a statement of sustainability and social awareness. Municipalities including New York City, Boston, and Washington, D.C., have emissions reductions laws targeting building owners with fines for excess emissions, creating cottage industries around increasing building efficiency. And even the Securities and Exchange Commission has mandated emissions disclosures from public companies. While anti-environmental, social, and governance, or ESG, campaigns have made the term a bad word, investors and tenants increasingly want and demand greener office space and assets that have a smaller carbon footprint.

THE SELF-MONITORING SOLUTION

The solution many techies seek is a building that monitors itself. Last fall, PassiveLogic released its Hive system, which autonomously controls building operations. Troy Harvey, CEO of PassiveLogic, called large structures “. . . immovable robots with tens of thousands of control points.” He sought tech that could “un-dumb a dumb thing.”

Many new buildings have begun to better utilize this technology, such as 555 Greenwich in Manhattan, which boasts a geothermal system to provide emissions-free heating and cooling; it utilizes AI to predict weather patterns and heating needs and adjust its energy systems accordingly. At 122 Fifth, also in Manhattan, owner Bromley Cos. has installed prescriptive data technology that uses sensors to automate energy usage and environmental systems with real-time occupancy data. And Carr Properties—which owns buildings in Washington, D.C.; Boston; and Austin—has utilized machine learning and analytics to more efficiently operate building systems, including better tracking room usage to reduce garbage disposal costs and proactively fixing plumbing and mechanical systems. Its 1-million-square-foot One Congress skyscraper in Boston has cut its energy bills by more than 25%, in part due to this effectiveness.

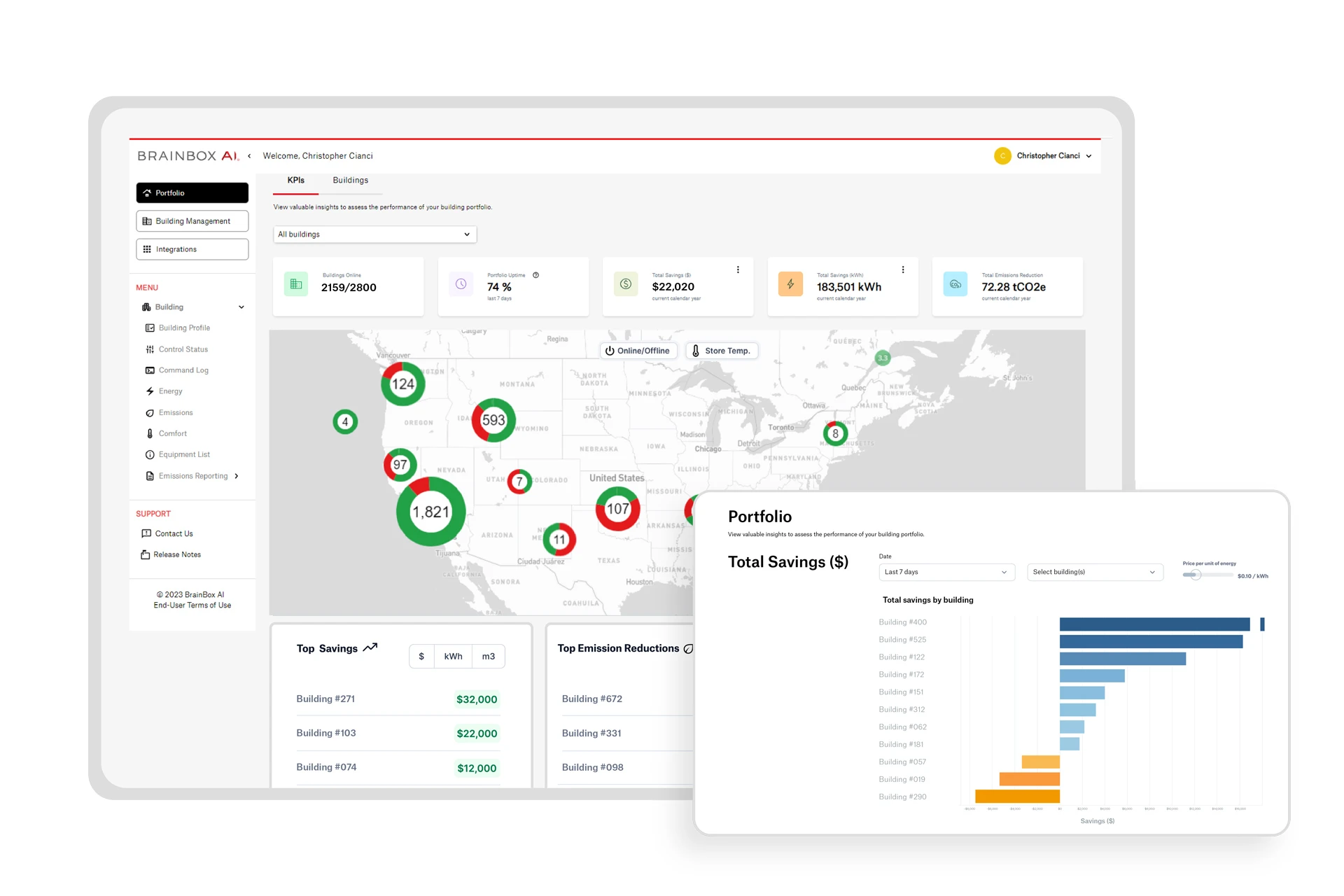

Firms like BrainBox AI, founded in 2017, also see automation as the key to slashing energy efficiency. CEO Sam Ramadori views the company’s technology as akin to the core tech behind the self-driving car, something scalable, self-learning, and autonomous that can make decisions and make a difference on building emissions. BrainBox AI now has software and systems installed in more than 1,300 buildings, all operating autonomously.

“We have a pretty far reach as well, from very large, complex buildings, like an airport, or a very large office tower or shopping mall, all the way down to a small convenience store,” Ramadori says.

A NEW ERA OF AUTONOMOUS BUILDINGS

The idea of autonomous building controls may seem fairly mainstream, with consumer products like the Nest thermostat already widely in use. And indeed, artificial intelligence isn’t new to the building world, says Robbie Hobbs, chief product officer at JLL, a real estate brokerage and services firm that runs its own technology and tech investment arms.

But the possibilities of using generative AI are just being realized, with building operations teams seeing applications for sustainability, dynamic cleaning, and even predictive maintenance. JLL Serve, for example, the company’s newly updated AI-enabled building management system, will help systems optimize for occupancy, and adjust controls, without any staff needing to alter thermostats or manually adjust mechanical systems.

Ramadori says most technology out there today is reactive: Heat goes up, then air-conditioning is triggered on. BrainBox, on the other hand, looks at outside temperature modeling, utility rate structures, and energy mix forecasts of how building occupancy and energy needs change over time. In comparison, he says, traditional systems are like driving with 80% of your windshield covered in black paint.

“You suddenly become a pretty bad driver, right?” he says.

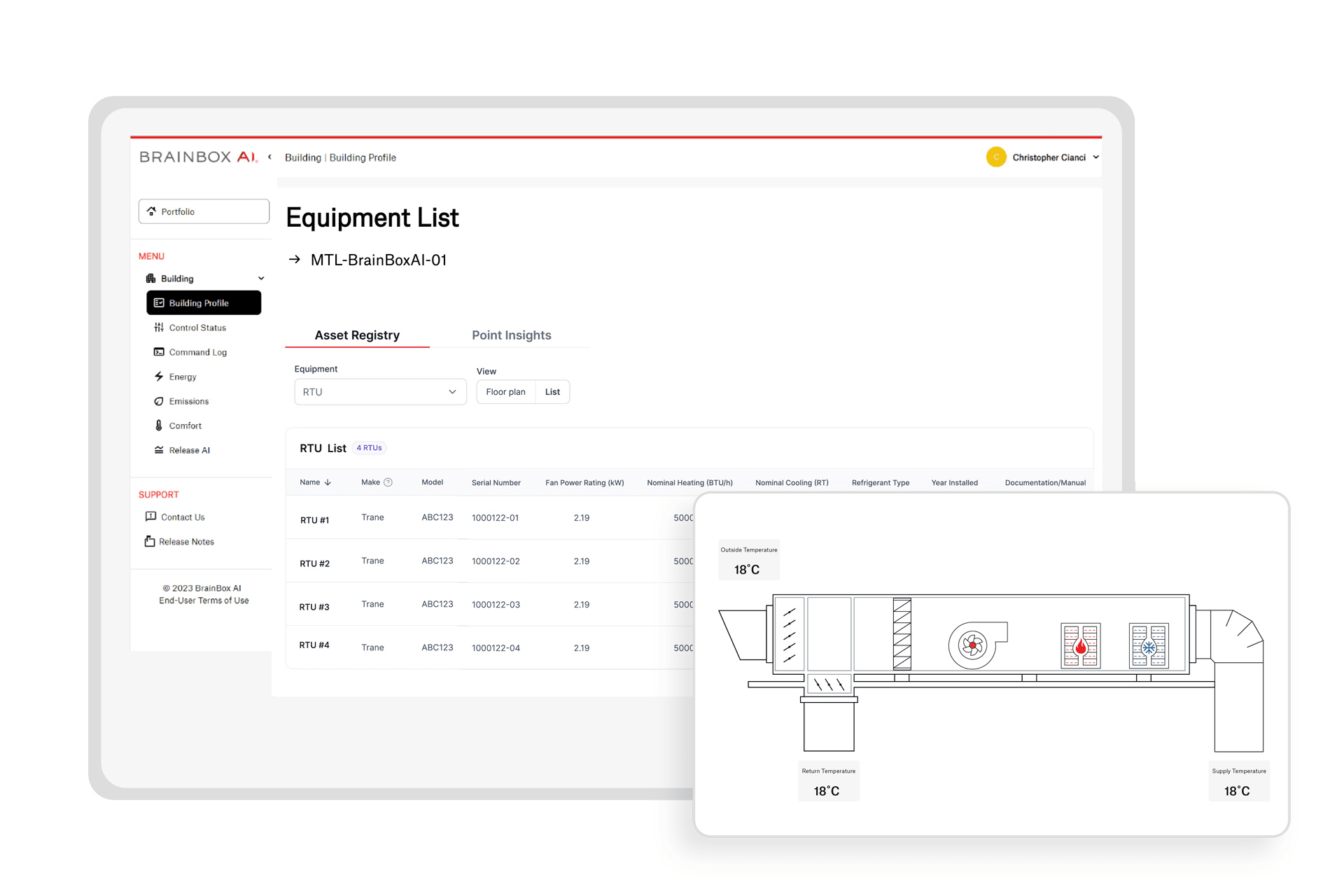

That smoother ride translates into substantial energy savings, even for buildings already built for better performance. Ramadori estimates that a typical LEED Gold building might use 30% less energy than a traditional building. With BrainBox tech, that can be cut up to an additional 20%, he claims, for the cost of a software subscription, as opposed to a retrofit with new insulation, appliances, and windows. At the Schreiber Center, BrainBox AI plugged into data from the existing sensors and software system running the building’s HVAC and adjusted existing controls.

PUTTING AI TO WORK

The Schreiber Center’s yearlong trial, bankrolled by the nonprofit Great Lakes Protection Fund, utilized a combination of different technologies. Marginal Operating Emissions Rate, developed by a startup called WattTime, helps measure the emissions being generated by the grid at any one time and coordinates energy use with peak renewable production. And BrainBox’s Automated Emissions Reduction algorithm helps the building store up thermal energy within the HVAC system.

In tandem, the two systems encourage the building to draw power when it’s least polluting, and then store and discharge it during the day. The system was fully autonomous, tapping into the existing network of hundreds of sensors to control different aspects of the building, including heating, cooling, and lighting.

What excites Ramadori is the ability for these kinds of newly smart, autonomous buildings to be better parts of a wholesale change in energy grids. This type of technology can more fully utilize renewable energy production—which often peaks and even overproduces during windy or sunny periods of the day—and curtails energy use during times of peak fossil fuel use. It not only cuts overall energy use, but shifts the kind of energy being used.

BIGGER QUESTIONS TO ANSWER

The development of building efficiency tech has run in parallel with the fate of proptech, startups focused on building and real estate tech. The industry has seen funding wither in recent years as interest rates rose, with venture capital funding dropping 42% in 2023, and some big-name ventures flaming out or facing financial reckoning, such as Veev and smart glass maker View.

Commercial real estate also has historically been slow to adopt new technologies. Whereas cars get swapped every eight years or so, buildings and their existing mechanical systems can be around for decades.

There’s also a workforce and skills gap; the recent turn toward more sustainable building technology has set off a push to train more workers to fill much-needed roles as building techs; roughly 2 million Americans already work in building energy efficiency roles. The industry tends to respond to the issue of displacement and job loss by suggesting this technology will simply free up existing workers to do higher-order, more important work, according to JLL’s Hobbs. The International Facilities Management Association released a statement this year that expressed, in part, the industry’s “apprehension” around the technology.

But recently, the advancements in generative AI have helped improve these systems, and suggest further iterations and even breakthroughs in the works. BrainBox plans to launch a virtual building engineer later this year to help building managers operate. Hobbs says that the increased amount of data these systems will be able to process will mean portfolio managers who oversee multiple buildings can better direct resources to those that need sustainability upgrades, and even evolve their investment strategies to better realize energy savings at scale.

There are still substantial challenges to more wide adoption of autonomous controls in commercial buildings. Cost can be a factor: Ramadori wouldn’t reveal the cost of the installation or ongoing subscription fees for BrainBox AI, but he did say payback happens within a year, and the typical monthly subscription fee remains much smaller than the total energy savings a client sees from its use.

One of the most pressing issues is the missing middle: Roughly 20% of such structures, typically the largest, have building management software systems that can be plugged into something like BrainBox AI. And for the bottom fifth of buildings—the smallest—it remains cost-effective to install the necessary sensors to make such a setup work. But the vast middle, which lacks such technology but would be cost prohibitive to wire up, presents a serious challenge that the industry is still struggling to solve. It’s all about tracking and utilizing data, Ramadori says, noting, “The built environment is either the number-one or number-two asset class in the world, and it generates data every day, and a lot of it just goes in the garbage. In this day and age, that’s almost criminal.”