- | 1:00 pm

The age of reboots and sequels: What’s motivating nostalgia bait?

Marketers know that anxiety-prone millennials and Gen Zers are particularly vulnerable to nostalgic appeals and more likely to seek the soothing balm offered by this kind of content.

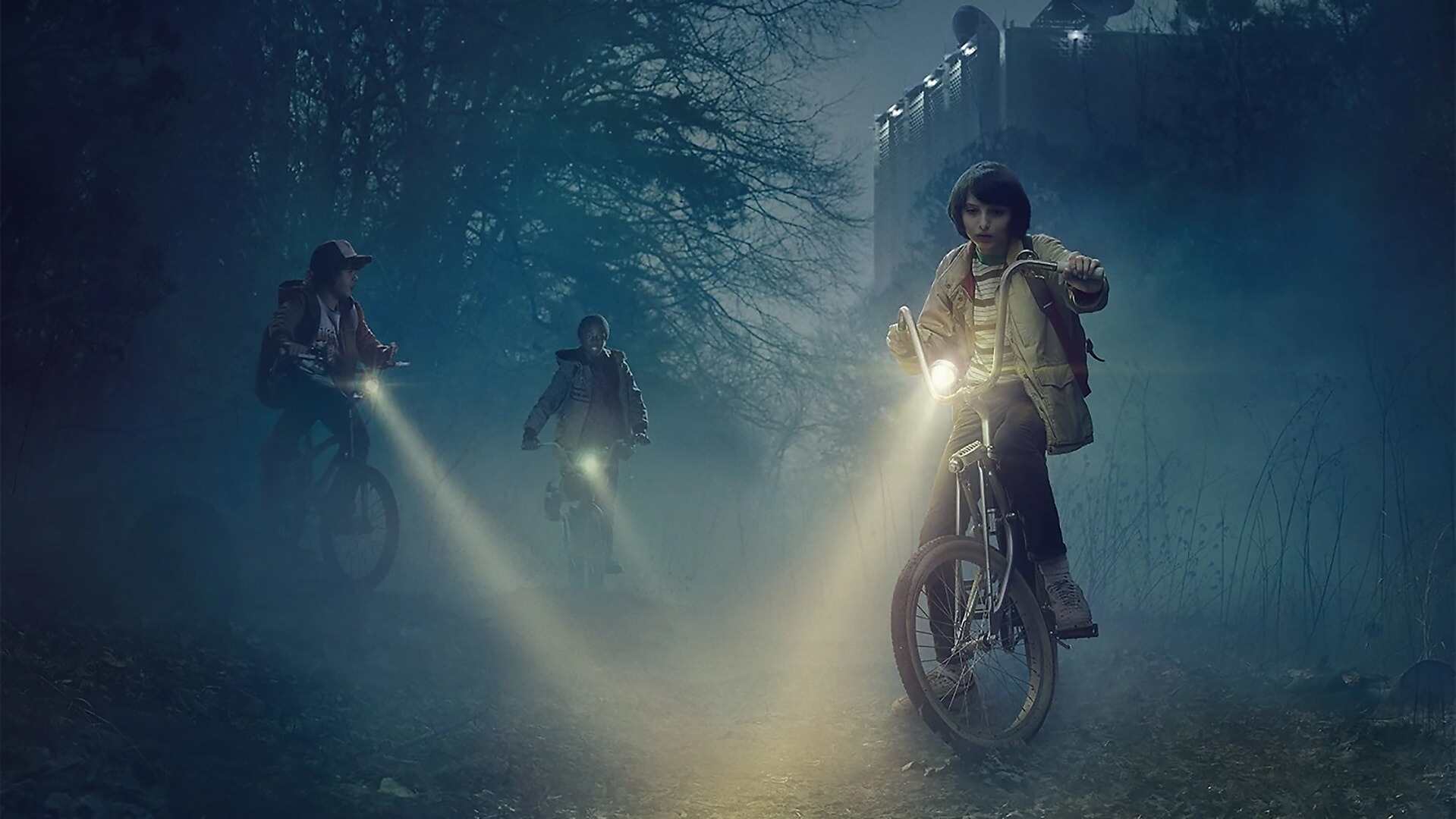

If you’re a millennial or a member of Gen Z and immersed in our culture’s current obsession with reboots, reenactments, sequels, and prequels, then you may be feeling a bit of nostalgia fatigue and asking yourself: Haven’t we been here before?

From the recent Mean Girls reboot to upcoming sequels for films like Megamind and Moana, contemporary popular entertainment seems to be rooted in the continuous (re)manufacture of memory. Indeed, the practice of leveraging our fond memories of the past for profit has a name: nostalgia-baiting.

The word nostalgia comes from the Greek nostos, meaning “homecoming,” and algos, meaning “pain.” Put another way, the word nostalgia refers to the specific form of pain felt when we attempt, but are unable to, return home. Nostalgia is homesickness.

When we engage with nostalgic media, we are, in essence, engaging with media that attempts to take us home—often to our childhoods, when we weren’t burdened with the stresses of adulthood, or even to a time of perceived simplicity, which we may not have experienced ourselves. The past is framed as a refuge from the chaotic present.

Like Dorothy, we are clicking our ruby red heels together and whispering “There’s no place like home.” But as the word itself would imply, we cannot go home.

HOMESICKNESS . . . FOR PROFIT!

On May 15, the theatrical trailer for Wicked dropped. Is this yet another instalment in the saga of nostalgia-baiting? The film features Ariana Grande, a figure likely to inspire nostalgic memories in those of us who first saw her singing and dancing her way through Nickelodeon. But the trend of nostalgia bait isn’t restricted to millennials and Gen Z.

After all, Wicked is an adaptation of a 2003 Broadway musical, which was itself an adaptation of a 1995 novel. That book was a retelling rooted in the classic 1939 film The Wizard of Oz, which was adapted from L. Frank Baum’s original 1900 novel. Aside from these most notable works, there have been numerous other retellings, remakes, and revivals since 1900.

Wicked illustrates how nostalgia has long been a strategy of the culture industries. After all, there is a financial logic in recycling already successful products, stories, and styles.

But if you’re feeling like the practice of rehashing the past is more prominent today, there’s a reason: Digital platforms make this long-standing trend more apparent to users, especially younger ones.

Within hours of its release, the Wicked trailer had already been recirculated and recycled online, an object of commentary and discussion, rapidly making its way down a digital yellow brick road through YouTube, X, Instagram, and TikTok. This doesn’t even take into consideration the photos, work-in-progress footage, songs, and teasers that have been circulating since last year.

The film’s advertising budget is designed to ensure that Wicked becomes inescapable to anyone online. It is this broad commercial strategy that has helped to amplify nostalgia’s ubiquity today. The uniquely acute nostalgia fatigue you may be feeling is rooted in the fact that millennials and Gen Z are the primary consumers of this digital content.

TEMPORARY RELIEF

We know that nostalgia can offer relief during stressful times. For instance, one study showed that during the early days of COVID-19, nostalgia was one of the tools we used to combat loneliness.

In his book Past Forward, psychologist Clay Routledge explains that nostalgia can act as an exercise in social connection: Nostalgic media emphasizes your connection to a collective past and your shared preferences, and can therefore reduce your feelings of isolation.

If you are in these cohorts then you have probably experienced COVID-19 shutdowns in your formative years, along with the ever-present climate crisis, the cost-of-living crisis, and the added mental health pressures of increased digital engagement—alongside acute feelings of loneliness.

With all that, it makes sense to seek a refuge from the present by reaching into the past—that you figuratively long to “go home” is logical and normal.

However, backed by billion-dollar corporations, marketers know that you—and other members of the anxiety-prone millennial and Gen Z cohorts—are particularly vulnerable to nostalgic appeals and more likely to seek the soothing balm offered by this kind of content.

The question is, how can you engage with nostalgia responsibly both within your culture and inner lives? Awareness and action are key.

IN THE PRESENT

The public relations pioneer Edward Bernays—who built on the theories of his uncle, Sigmund Freud—argued that to successfully engineer the consent of the masses, you need to appeal to their subconscious emotions. In other words, marketing strategies work best when we are unaware of them.

By recognizing that many nostalgic visions of the past are little more than profitable fictions, we strip them of some power. It is the equivalent of pulling back the curtain and seeing the great and powerful Oz as a mere man. Nostalgia itself isn’t bad, but we need to remember that we tend to experience it as it has been repackaged to us as attractive fictions rather than reachable realities.

Sometimes, longing for the past can result in dissatisfaction with the present.

Remember that the feeling of pain is embedded in the word itself: nostalgia is homesickness—a very concept that evokes illness and disease. With this in mind, if your nostalgic engagement results from—or is intertwined within—a disappointment with the present, use these negative emotions to motivate change. And always be wary of forces that try to leverage your nostalgic emotions for their own gain.

Rather than lose yourself in nostalgic reveries, ask yourself what is it in the imagined past that so appeals to you and how might you be able to achieve something comparable in the present? This process of reflection may allow you to actively improve the present rather than seek shelter in the past.

After all, even Dorothy returned to Kansas a changed person.

Selma A. Purac is an assistant professor of media studies at Western University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.