- | 9:00 am

How this ‘Godfather of Sustainability’ persuades CEOs to change their business

In a half-century of trying to open the minds of the C-suite to the benefits of sustainability, John Elkington has learned some lessons about getting CEOs on board.

Looking back, I don’t remember anyone ever advising me to enter business as a shark tickler. Still, while some brave people risk life and limb taming lions and tigers, I set out to rein in the corporate world’s man-eaters—or “the future eaters,” as Tim Flannery dubbed them in his book of the same name.

These are powerful people, businesses, and industries able (and willing) to dictate the fates of thousands, millions, even billions of people. Over time, I have come to see some of them as the market equivalents of the great white shark that dominates Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster film Jaws, launched in 1975, just as I was starting the journey that I describe in my 21st book, Tickling Sharks.

At times, the experience has been far from pleasant. Indeed, at times it was terrifying, as when we were sued by the not-so-amiable fast-food giant McDonald’s. I tell the story of how all this began, what life has been like inside the maws of some of the world’s biggest corporate predators, and what I learned along the way as we tried to speak tomorrow’s truth to power.

Cue the Jaws soundtrack. Once heard, it’s virtually impossible to get the music from Spielberg’s film out of your head—the ominous, two-note score that accompanied a series of full-blooded shark attacks projected into darkened cinemas worldwide and later into our homes. It proved to be the ultimate earworm.

It also had one unintended consequence: a testosterone rush among shark catchers along the Eastern Seaboard of the U.S., with thousands joining a frenzied hunt for the living incarnations of Spielberg’s mechanical models.

In the years following the film’s release, the number of large sharks off the East Coast plummeted by around 50%—a cameo of the wider story in which life on Earth has found itself sucked into and shredded by the jaws of capitalism.

Even before that catastrophe, I had morphed into something of a Trojan Horse, determined to breach the once-impenetrable walls of business. For half a century now, I have worked to open up business minds and cultures to what we now call the sustainability agenda. Early on, it proved virtually impossible—with top people in business quite literally seeing anyone with a green agenda as red, a communist.

Despite understandable criticisms from today’s even more eco-anxious youngsters, though, I argue that we have made remarkable progress, at least in some areas. Indeed, that’s why I felt comfortable using the subtitle How We Sold Business on Sustainability for Tickling Sharks.

Consider just one growth area. When, back in 1987, I cofounded the company SustainAbility (now owned by ERM, itself owned by KKR) the term was pretty much unknown. So we joined up with the United Nations to promote corporate sustainability reporting—something many companies at the time found somewhere between hard to digest and unthinkable.

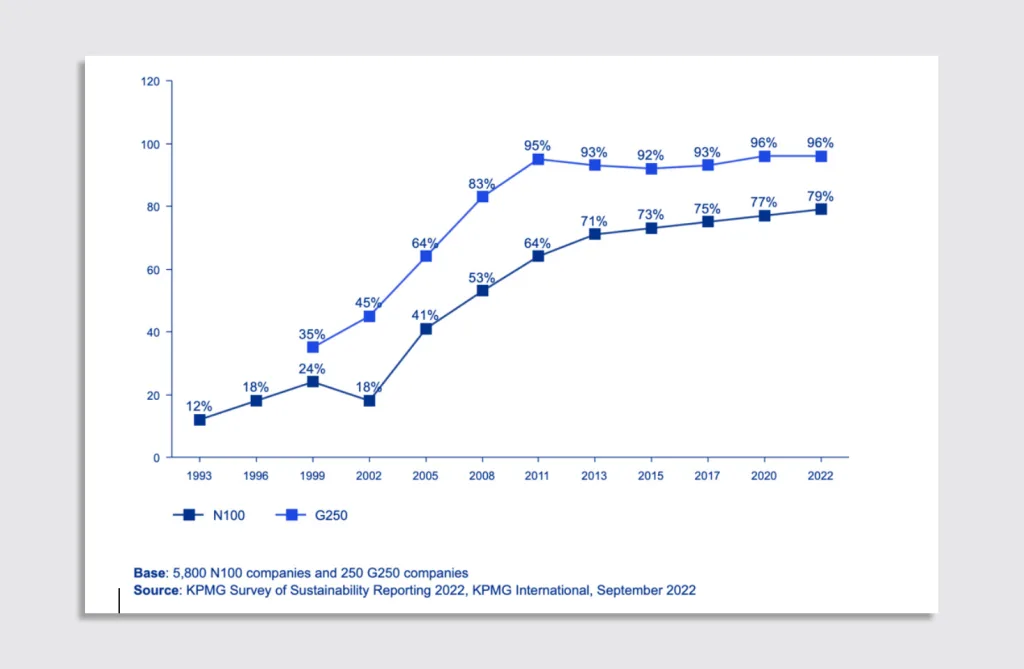

Today, as the diagram from KPMG below demonstrates, most major businesses produce annual sustainability reports as a matter of routine. I welcome the trend, of course, though it’s often a case of too little, too late.

Now, with the supply of corporate sustainability data about to expand further with the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, maybe we should ask ourselves whether the supply of data is in danger of outrunning demand and practical usage.

How many businesses are using all this information to produce meaningful market intelligence—and how many governments are using it to help them in the critical task of planet management? Way too few, though the AI boom may help boil this particular ocean, in a good way.

I offer some hard-won how-to lessons in the book. So, for example, if you want to speak truth to power, I suggest, have a word with yourself first. Know who you are, what you stand for, and how you are likely to be experienced by others. We all have our flaws and our weak spots, so a little self-knowledge goes a long way.

Above all, try not to become emotional even when talking about emotive subjects. Sharks are acutely sensitive to signs of distress.

Know, too, that many powerful people do not feel remotely as powerful as you might imagine. Some will know all too well that change is coming, even as they try to avoid speaking about it, let alone delivering it.

Once we used these tricks to get CEOs and other business leaders to pay attention, we saw a period in which a growing number of companies insisted on knowing what the “business case” for action might be. Which issues were financially “material,” they asked. Often, they were stalling for time.

Then, spurred by billionaire philanthropists like Bloomberg, Gates, Omidyar, and Skoll, the changemakers they invested in were pushed hard to scale and replicate their positive impact. That era, in turn, spurred growing interest in new, sustainable business models.

Now, almost regardless of what happens in America’s November elections, the spotlight is shifting once again, from business models to economic models. And, in the process, from individual businesses—including their brands, boards, business models, and supply chains—to the dynamics of the markets that so powerfully shape business thinking.

So our question today must be: How can we design tomorrow’s markets so that they incentivize CEOs and other business leaders to deliver sustainability outcomes as a matter of course—not simply as an exercise in corporate citizenship?