- | 8:00 am

This marble-like building material looks out of this world. It’s actually auto industry waste plastic

Earthly recycled plastic could become a new kind of building facade.

A new kind of building material is taking shape in a lab at the University of Michigan.

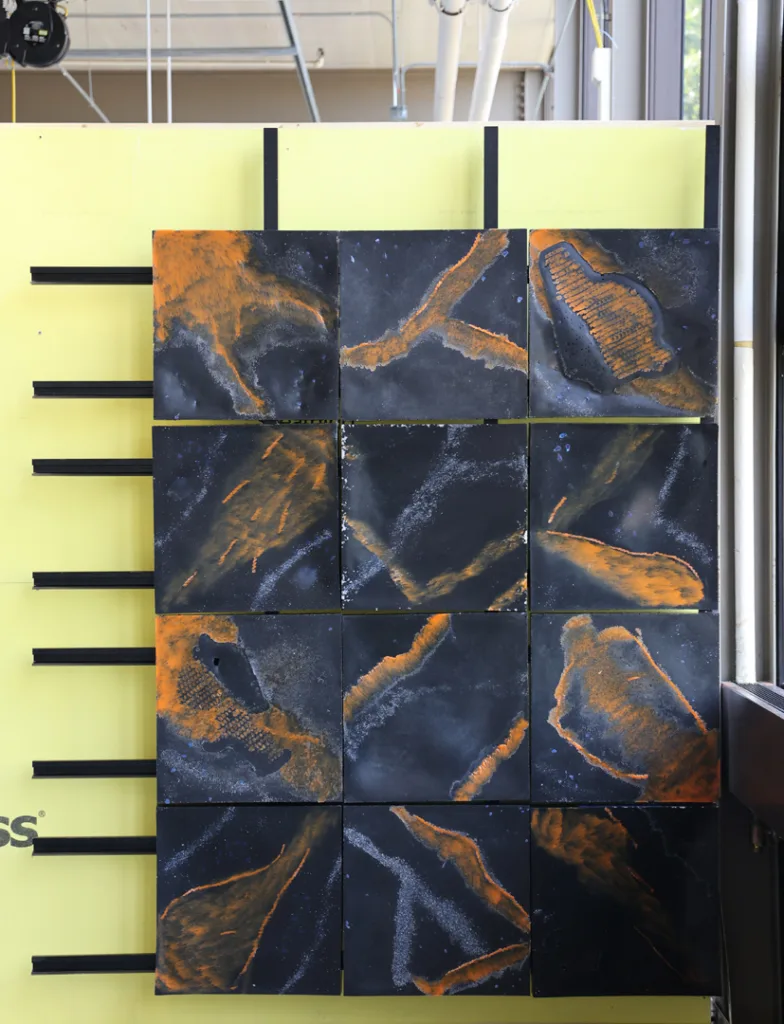

The modular, flat black panels panel is the kind of wall-like material that’s used to clad the exterior of buildings, which are often made of concrete or stone. It’s marbled through with eerie streaks of orange, making it look like a slab of rock quarried from some alien landscape. This slab, though, is made of melted waste plastic from the Detroit auto industry right here on Earth.

The slab is called Post Rock, and it’s a prototype of a recycled plastic building material that can dramatically reduce the carbon footprint of buildings. Now on display in an exhibition at the Craft Contemporary museum in Los Angeles, Post Rock is an attempt to reduce the building industry’s large environmental footprint by reusing the waste stream of another, completely different industry.

One industry’s waste material becomes another’s solution

The concept was developed by Meredith Miller and Thom Moran, two professors in the architecture department at the University of Michigan who have been looking at ways of using waste plastic to create new building materials since 2015. The pair were inspired by the phenomenon of plastiglomerates, or composite rocks formed in the ocean from waste plastics, sand, and other debris. Appearing both natural and unnatural, these rocks highlighted a global waste problem but also hinted at new ways waste plastic could be put to use.

Miller and Moran, who help run the architectural practice T+E+A+M, saw both a material and an aesthetic opportunity in this recycled plastic building material. “We had this idea that waste plastic could be made to seem more valuable through design,” Miller says.

They began experimenting with using waste plastic as a kind of malleable base material for architectural objects. Early experiments used melted plastic as the binding core of columns made from waste material. Using ground-up waste plastic that came in a variety of colors, the melted output of these experiments began to look strikingly similar to rock, one of the oldest architectural materials on earth.

That recognition evolved into explorations of using just plastic on its own. As architects they realized that, under the right conditions, plastic could form some of the basic materials used in building projects around the world. Instead of digging marble out of the ground, they saw a way to use the coloring in their plastic experiments to create a new kind of alternative building exterior.

With a patented thermoforming process that uses heat to melt a mixture of plastics, along with a robotic arm that rotates an encompassing cast as the molten plastic sets, they’re able to turn waste plastics into solid forms with swirling, stone-like veins in bright colors. “We’re not hiding the fact that it’s plastic,” Miller says.

A new beginning for plastic waste

Now, they’re trying to turn that idea into a product. “We really started the project as architects, as designers. But I think we’ve had to learn how to be researchers and entrepreneurs,” Miller says. “If we really want to have impact on the problem of waste then we can’t just be making one-offs in our lab, but we need to create something that can scale.”

With a grant from the National Science Foundation, Miller and Moran and University of Michigan fabrication research specialist Christopher Humphrey tested a wide range of waste plastics to see which would work best as this new kind of recycled plastic building material—not just aesthetically, but performatively.

“There’s this idea that plastic is a single material, but it’s actually a kind of technology. And each kind of plastic is engineered for very particular uses,” Miller says. “To find new end uses, you have to be really specific about, well, what kind of plastic are you recycling?”

A distinct utility and aesthetic

Trying to make a product meant that they had to find base materials that could comply with building safety regulations. “So that brings us to the obvious barrier to bringing this to market, which is that petroleum-based polymers are very flammable,” Miller says.

This is where the automotive industry comes in. Through their research, Miller and her collaborators learned that many plastics used by the auto industry are already fire resistant. Typically used to cover electrical wires or batteries or form the dashboards of cars, plastics like polyamides meet the fire safety standards that govern what can be used on the exterior of a building, and also worked with the thermoforming process the researchers developed.

And these plastics are abundant. From their lab in Detroit-adjacent Ann Arbor, Michigan, the researchers saw a rich source of waste plastics coming from the region’s auto industry. Automotive companies and suppliers in the Detroit area produce more than 300,000 tons of plastic waste annually, they found.

They’re now using waste polyamides to form Post Rock panels, and using the often orange coloring of the source plastic to be a kind of signature veining in the material that’s reflective of its origin. “This is a version of Post Rock that is very much regionally sourced through the automotive industry. And hopefully you can see that. So the aesthetic is really born from this region,” Miller says.

The panel on display at the Craft Contemporary exhibition is still a prototype, but Miller says the concept is evolving quickly, and getting closer to commercialization. The team is still working on refining Post Rock to comply with National Fire Protection Agency regulations for building materials, but expect to hit that goal within a year.

At the same time, the designers are still working to ensure the panels that come out of this process carry some of the fingerprints of the plastics used to make them. “It was always important to us for this to be visual,” Miller says. “There’s recycled content products that are used for insulation or subflooring or things like that, and I’m glad those exist. But I think as architects and as designers, we’re ultimately thinking about how this will impact what buildings look like.”