- | 9:00 am

This simple paper sensor could change how we respond to future pandemics. And it costs only $1

A simple solution for a big problem.

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced everyone to the world of PCR tests and lateral flow tests but since then, a different type of testing has quietly been gaining momentum.

Wastewater testing is a burgeoning method that has become key to monitoring public health in countries around the world. That’s because scientists can use it to track infections before people even show symptoms by analyzing sewage coming out of a local community, a university dorm, or an airport—giving health professionals and government officials a head start in containing outbreaks. That being said, it also has a serious hang-up: The lab work is slow and expensive, making it inaccessible in many parts of the world.

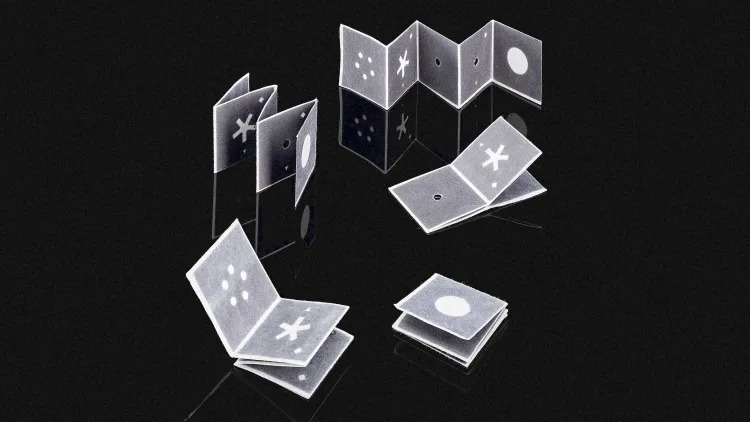

But this conundrum could soon change with a new, origami-inspired paper sensor that can detect diseases without the need for electricity or even specialized equipment. All it takes is a special piece of paper that you fold and unfold in specific ways, like you would an origami paper. It costs only $1 per test—and it could be commercialized within the next two to three years.

A new approach to existing science

Wastewater testing dates back to the early 2000s, when it was largely used to estimate drug consumption in the U.S. But the COVID-19 pandemic brought the technique back into the spotlight. In 2020, the University of Arizona started screening the sewage from each of its dorms, and ended up catching a COVID-19 outbreak in one of its dorms before it even started.

The practice has also been popular in the Netherlands, where the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment started monitoring wastewater from more than 300 locations across the country, several times a week.

The researchers behind this clever Origami wastewater test, at Cranfield University in the U.K., also developed an earlier version, which they put to the test in 2020 at four quarantine hotels in Heathrow Airport. The test could detect COVID-19 as efficiently as a PCR test.

A design for easy use

The new test consists of five squares folded into an accordion. Each square contains specific chemicals designed to process the sample step by step.

First, you fold the first two squares, then squeeze a sample equivalent to a finger prick into a designated hole. Then, you add another liquid to wash off any impurities and “isolate” the viral particles. Then you fold the remainder of the accordion into an elution cassette designed to help extract and purify specific substances. Once the biochemical reaction is complete, which takes less than hour, you can read results with the naked eye: a green circle suggests a positive; a blue circle indicates a negative.

By virtue of its material and size, the test is thin, lightweight, and easy to transport. But most importantly, it’s designed to be so easy to use that even a non-specialist can do it. This means it could eventually be deployed in rural or remote areas, empowering local communities who might not have the resources to test their wastewater and stay ahead of the curve.

Unlike the previous iteration, the new origami-inspired test can also detect e-coli, salmonella, malaria, and other pathogens. The scientists used it to test for malaria in a Ugandan primary school, as well as for bovine infectious reproductive diseases in rural India.

A simple solve for a complex problem?

“We are interested in working with NGOs to eventually implement it as a user-friendly diagnostic tool for people who have no resources but want the promise of diagnostic results,” says Zhugen Yang, lead researcher and professor of biosensing and environmental health at Cranfield.

Today, Zhugen says that more than 70 countries around the world have implemented some form of similar monitoring program, whether it is regional or national. But that method remains complex and costly. The samples must be collected on-site, then stored and transported in a cold chain, before being processed in a lab up to 24 hours later.

In contrast, the origami test can be used on-site with results available within an hour. Coupled with its low cost, it could drastically improve how we track infectious diseases, and respond to future outbreaks, by providing early detection in almost real time. As Zhugen puts it: “It’s an early warning system.”