- | 8:00 am

Many scientists are neurodivergent. Architects are finally starting to build labs designed for them

New research labs are being built with flexible layouts and different levels of sensory input to give employees more choice about how they work.

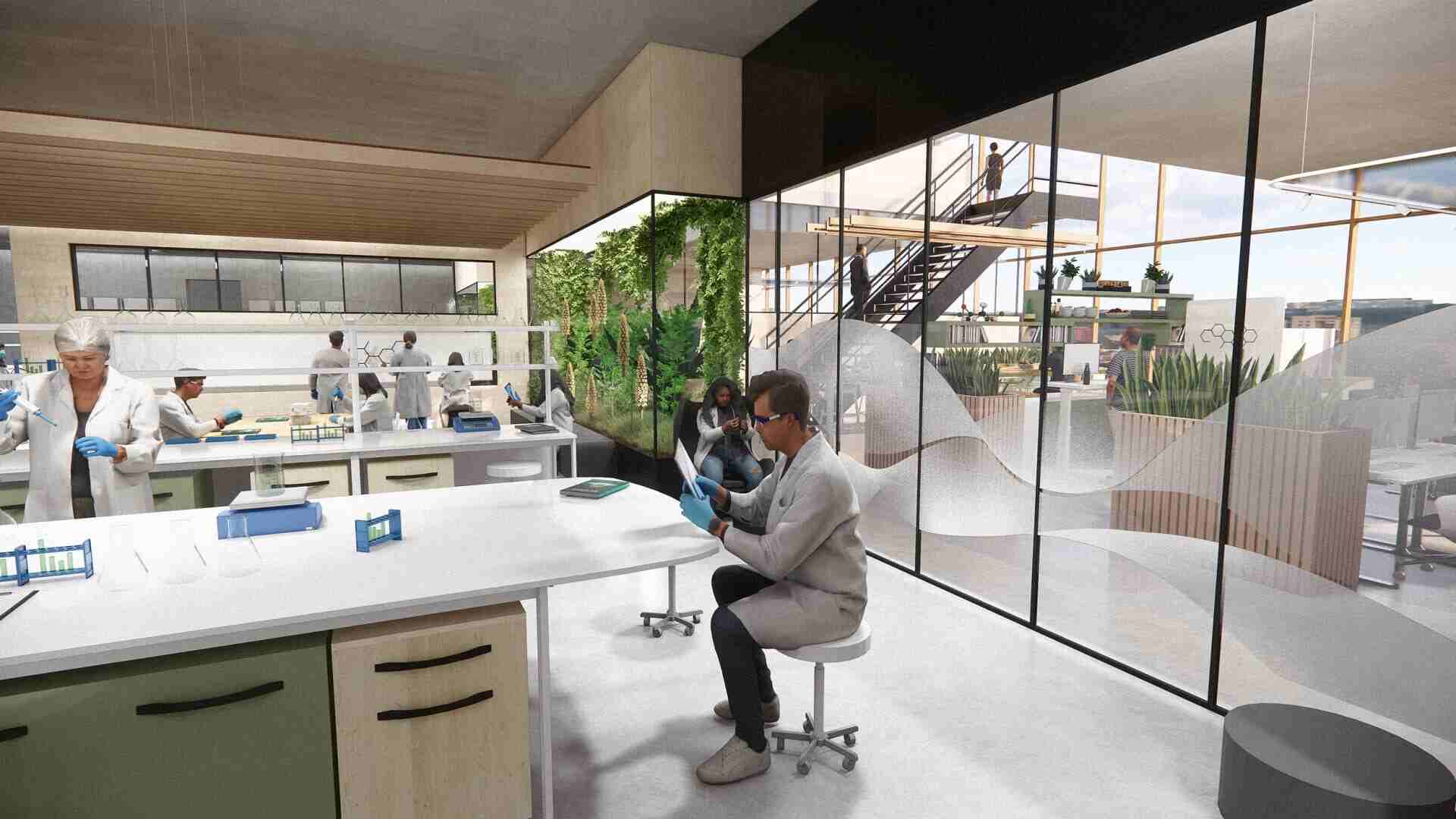

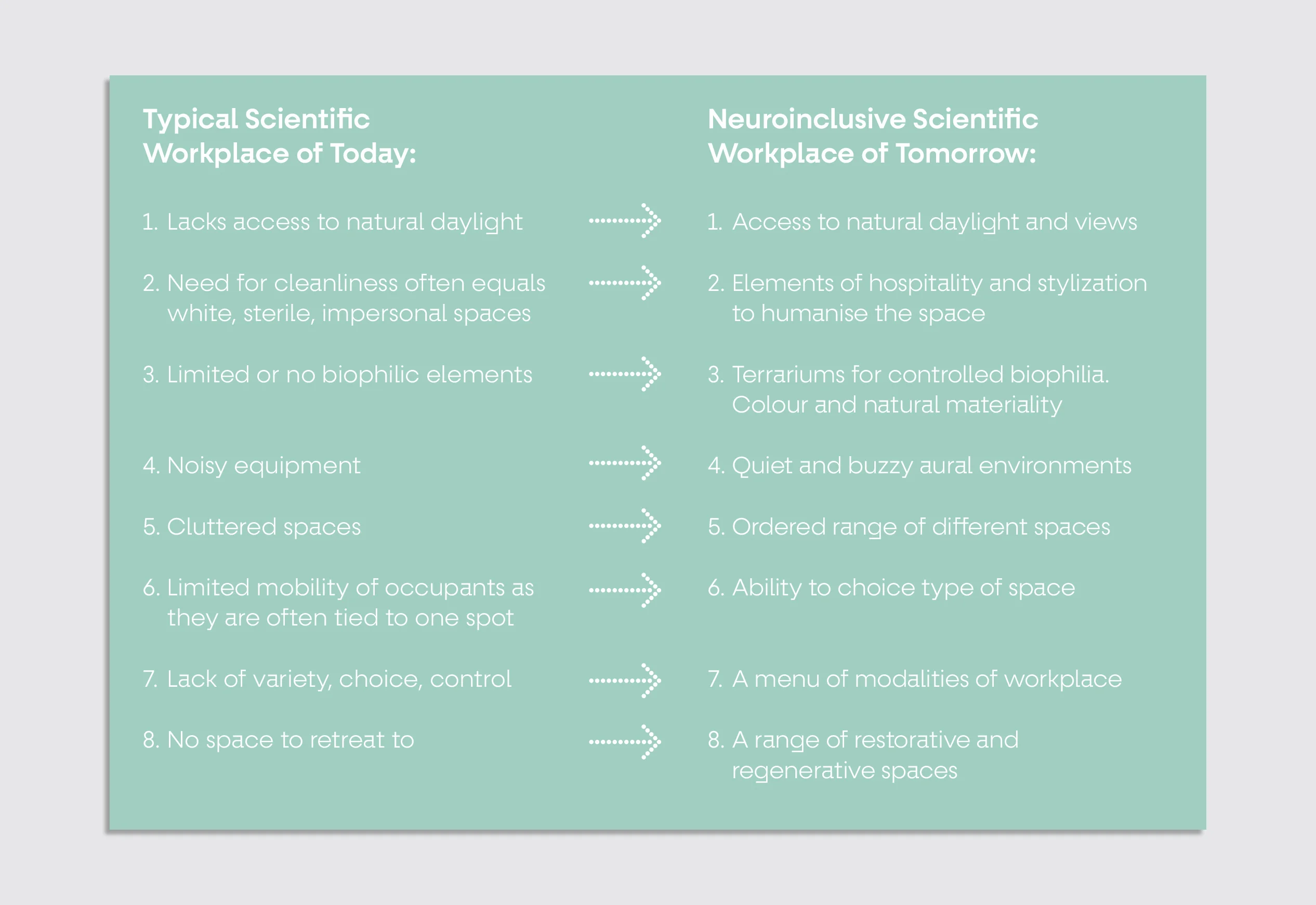

Imagine the stereotypical biotech lab space: smudge-free counters and walls, blindingly white surfaces, and an array of stainless steel machines, all set up for maximum focus and cleanliness to further the pursuit of innovation. But a new study about the way different kinds of scientists use lab space suggest the one-size-fits-all approach isn’t just aesthetically sterile, it might actually inhibit scientific research, and require a new design approach to fix.

Roughly half of lab workers and scientists identify as neurodivergent, or somewhere on the autism spectrum (double the global average of 20%), according to new research conducted by Advanced Research Clusters (ARC), a British developer of lab space, HOK, a global architecture practice and the University of the West of Scotland. The same survey found the rate of autism among lab workers is 25%, or 25 times the U.K. average.

That’s an opportunity to rethink design and radically change how labs look and operate, says HOK principal Kay Sargent, the firm’s director of thought leadership for interiors. The research found a gaping need for inclusive scientific spaces that holistically look at and rethink auditory, visual, and tactile elements to eliminate sources of disruption and disengagement.

In short, Sargent says, traditional lab design raise a key question: “Are you eliminating the potential for people who are really going to be game changers to be successful?”

A new blueprint

This research led HOK to put forth a blueprint for a more inclusive lab design. It’s a set of principles and design ideas that researchers, architects, and designers believe will make lab spaces more comfortable for all. Many of these ideas will be adopted and included in the firm’s forthcoming design for AstraZeneca, the pharmaceutical giant that’s building out a new 570,000-foot, 16-story headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the nexus of the biotech industry.

They’re not expensive changes, and don’t really add much to the project budget, says Sargent. But they are thoughtful touches that can significantly improve productivity.

HOK has been studying the wider issue of design for neurodivergent populations for roughly a decade, motivated by the general lack of research on the topic. “There was a real drought of information, almost a total vacuum on how to design the built environment for sensory processing,” she says. “We believe really strongly that the environments that we’re designing will have an impact on the people in them, which can be good and bad.”

Roughly 18 months ago, ARC asked HOK to look into this issue as it impacts lab users, since they were fielding more requests for incubator space for small startups and wanted to improve the types of labs they were building.

A lack of sensory diversity can lead to reduced productivity, poor recall, burnout, stress, and recruitment and retention challenges. The downsides of business-as-usual facilities rarely gets addressed by workers, especially junior staff; just 30% of younger innovators consider themselves neurotypical, the study found.

“Often, neurodivergent employees will manage their work environments by hiding signs of their neurodiversity,” says Dr. Edward Edgerton, a University of West of Scotland, who participated in the research. “However, even when their neurodiversity is recognized, their workplaces can still be exhausting, impacting negatively on their performance and well-being. Few organizations have considered neurodiversity workspace design, particularly for laboratories.”

Life science real estate boomed in the early part of the pandemic, creating an arms race in terms of high-end amenities, outdoor space, and terraces and balconies. But Sargent says that amenity spending, and more comfortable dining and social spaces, doesn’t really solve the distraction problem for workers who spend their entire day within the research and work space. The goal was to create a more human experience for those within wet labs and scientific workspaces.

The solution, according to the research, is to create labs that include biophilia and a variety of workspace options; the layout caters to different levels of sensory input, not “one size misfits all,” as Sargent explains. The focus is on focus itself. The proposed design offers ways to cut down on different types of overstimulation and eliminate the impact of noisy equipment, while also providing more daylight, natural elements, and more choice.

That means bright colored walls to reduce the sterility of labs, but also nooks and crannies with less visual and auditory stimulation for private work. Meeting rooms should have flexible seating that allow for sitting and standing, as opposed to huddling around one large rectangular table. They also recommend reducing sharp edges, plastic and metallic materials, and see-through walls with more private labs and organic materials and shapes.

Rethinking the lab layout

Biology labs tend to cram in workers due to the financial considerations of real estate development; life sciences space costs multiples more than traditional office space. That tends to result in open, contiguous lab space, with regular rows of work benches, cellular support labs for imaging and tissue cultures on the ends, and a small amount of breakout space on the periphery.

HOK’s solution is a lab neighborhood, featuring a variety of neurozones meant to break up the floor plan and the workday. A mock 100-person lab prototype included in the report is subdivided into two wings, with a central bay that include congregate and creative space for collaboration. Commune modes of space, more akin to the standard layout, are next to the central bay to maintain financially required density, but sport a wider range of seating, benching, and furniture options.

Further out from the core, a number of differentiated spaces offer more varied, inclusive environments: a series of biophilic terrariums break up repetitious seating and views to create quiet space for hypersensitive researchers; contemplative pods offer spaces for group meetings and work; quieter commune spaces on the edges include more acoustic absorption and organic furniture and bench seating. In addition, the transparent barrier between lab areas would be replaced with fully glazed partitions to add visual privacy. This layout better integrates spaces for rest and relaxation amid work areas, and eliminates corner offices for executives, providing additional opportunity for needed shared space.

Sargent believes this kind of design approach offers the same benefits as universal design, which views architecture that make it easier for those with mobility, visual, and other disabilities to navigate a space as having society-wide accessibility benefits. HOK is actually doing a tracking study in one of its own offices, testing the impacts of this kind of design approach, and will continue to study the impacts of its newer spaces, which will utilize a similar approach to user diversity.

“I know no one who isn’t impacted by sound, color, temperature, or texture,” she says. “But what might be annoying for someone who’s neurotypical can be debilitating for someone that’s neurodivergent. They tend to be that canary in the coal mine, and they’re going to feel it first, and they’re going to feel it more intensely. But it doesn’t mean that it’s not impacting every other person in a space.”