- | 8:00 am

Why disco is having a moment (again)

In times of stress, people turn to escapist joy.

After running their luxury leatherwear brand, The Mighty Company, for the last eight years, Jessie Willer and Hanover Booth have learned a thing or two about what works on the dance floor. They say a big part of their brand’s DNA is making sure their clothing can “pass the dance test.” Meaning, people have to be able to boogie in whatever they make.

“So much of our friendship has happened on the dancefloor, yet so much of what people live now is almost a simulation,” says Willner. “So we became obsessed with a time earlier than ours.”

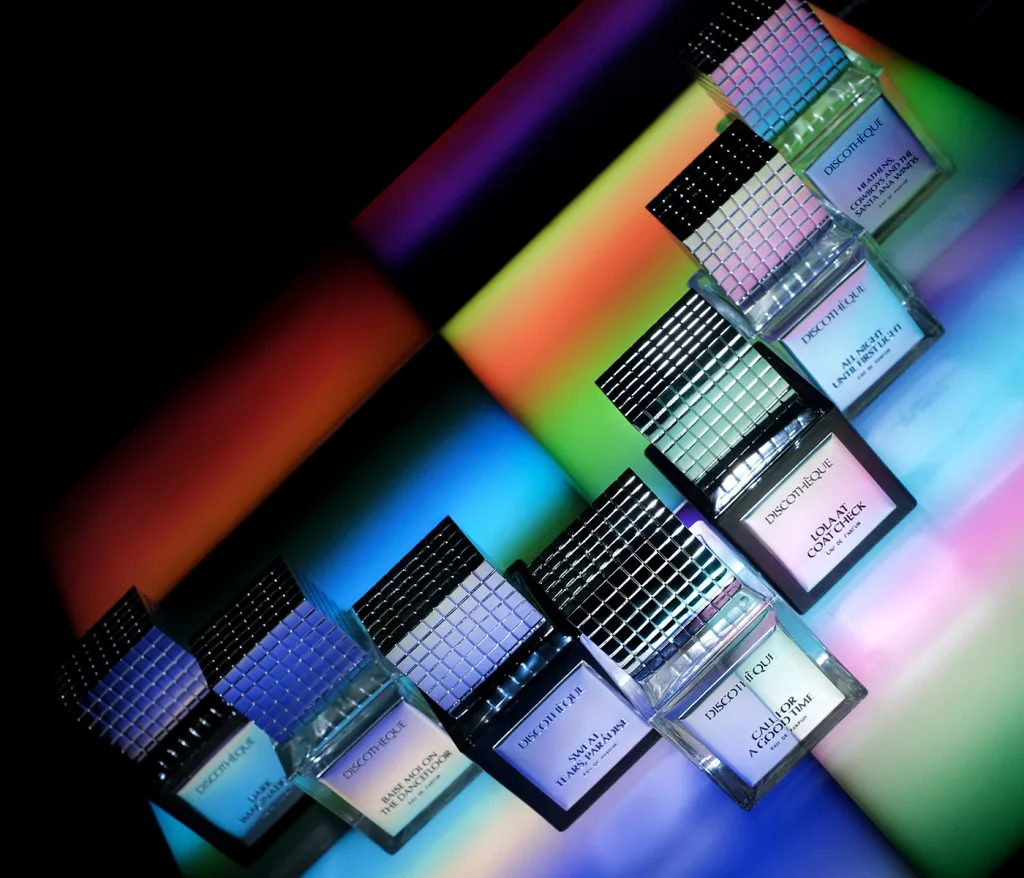

This led the designers to embark on a new endeavor—making a fragrance line called Discothèque Fragrances, where each home and body scent is inspired by a club in a particular city at a particular time. The perfume bottles are disco balls with sharp edges, complete with chrome and mirror finishes; the candle vessels’ color palette consists of highly saturated gradients that evoke the lighting system of a discothèque or a club.

Discotheque Fragrances is just one example of the disco renaissance that’s happening across industries, as brands tap into a pre-internet era where people had to actually go out to get inspired.

Disco’s re-revival

“A lot of moments come and go in popular culture; they come and go in a cycle. Disco has a shorter wave, perpetually coming in and out,” says Matt Hodges, creative producer at Spiegelworld’s Discoshow, an immersive, 1970s and disco-themed show that opened in September 2024 at The Linq Hotel in Las Vegas.

Disco has resurfaced periodically, starting in the 1990s when fashion and music turned back to the ’70s for inspiration. In 2001, Australian singer Kylie Minogue released the anthemic single “Your Disco Needs You.” Then 2002 saw the opening of the exhibition “Disco: A Decade of Saturday Nights” at what is now Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture. The 2005 Madonna album Confessions on a Dancefloor boasts a lead single, “Hung Up,” which heavily samples ABBA’s “Gimme Gimme Gimme.”

From a mainstream music point of view, disco was fully redeemed in 2013, when Daft Punk’s disco-inspired album Random Access Memories won Record of the Year at the Grammy Awards. In 2018, Vitra Design Museum hosted an exhibition about nightclub and discothèque designs, and in 2023, the V&A Museum’s exhibition DIVA devoted a sizable portion of the show to disco-era performers.

Disco music and its tropes are also being retooled: In 2020, Carly Rae Jepsen went disco with her Dedicated Side B, Dua Lipa with Future Nostalgia, and Beyoncé did the same with Renaissance (complete with mirrorball-inspired cover art). Kylie Minogue released not only the album Disco in 2020 but also the neo-disco anthem “Padam.” In 2022, Lizzo appeared at the BET Awards clad in a golden, mirrorball-inspired outfit, and mirrorballs are a throughline of Taylor Swift’s namesake ballad, where the addressee is described as “shimmering,” “beautiful.”

“I think there’s a reason so much current music sounds like disco music; because it’s got it in its DNA,” said Frank DeCaro, author of Disco: Music, Movies, and Mania Under the Mirror Ball, which came out in October 2024. “It’s the grandchildren of music from 50 years ago and of the push for empowerment from 50 years ago and the fight for equal rights, for commitment.”

DeCaro’s book doesn’t just focus on the music and club atmosphere, even though his playlists feature both deep cuts and well-known anthems. He also explores how disco influenced fashion (like designer jeans), TV (think, disco-themed episodes in The Brady Bunch), cinema (a lot of “so bad it’s good” selections), and Broadway, even if the results in the 1970s were mixed until jukebox musicals like Mamma Mia! came along.

“What I tried to do with the book was make sense of this movement that was so much more far-reaching than just what we heard on the radio,” he tells me. DeCaro wanted to explain to younger generations that disco was as all-encompassing as hip hop has been over the past 20 years, influencing everything.

For instance, the 2018 Vitra museum exhibition explored the idea of nightclubs and discotheques as hotbeds of popular culture and centers of avant-garde art forms. “Many clubs developed into a Gesamtkunstwerk, melding interior and furniture design, graphics and art, light and music, fashion and performance into a unique whole,” states the foreword of the exhibition catalog. The main disco-themed cultural products of 2024, namely Discoshow and Frank DeCaro’s Disco both make a case of its being an all-encompassing cultural movement. “Disco was a way to wear your clothes,” DeCaro tells me. “It was a style movement, a music movement, and a visual one.”

Discoshow has several environments where the audience (capacity 350) moves from a lobby that looks like the inside of a disco ball to a 1970s subway car with an East Village aesthetic, to a loft space, and finally, a dancefloor—there is also a diner, named Diner Ross. This type of set design seeks to emphasize how disco was situated in 1970s culture: for instance, the loft, which pays tribute to David Mancuso’s NYC space of the same name, contains a combination of vintage Italian design and ramshackle furniture, as if someone had furnished it gradually.“ We do get to the disco hits, but it immerses you into what—hopefully—feels like the context in which disco was born,” said Hodges.

On this note, the disco aesthetic works well for interiors. Just to make a couple of examples, the new Marni boutique in Milan, redesigned in 2022, looks like a 1970s club with its mirrored ceilings and highly-saturated carpeting; Bar Bonobo in New York is styled like an Italian disco.

Disco’s big moment

So why are we seeing the resurgence of disco now? The most obvious reason can be found in the COVID-19 pandemic, a moment when dancing in actual clubs was not available to the general public. “It’s always music that can get you on your feet when you need it most. And I think that whether it was during the AIDS crisis or during the COVID-19 pandemic, people needed to be cheered up and needed to be forced off their couches and to do what needed to be done,” says DeCaro.

DeCaro draws parallels between today’s political climate and that of the late 1970s, when disco began to die as a mainstream music genre. He says Disco Demolition Night was a turning point for the genre. At the event, held during a Chicago Red Sox baseball game, anti-disco fans turned out to blow up crates of disco albums. The event ended in a riot, surfacing the growing tension between the culture of disco and that of its detractors.

“The people who liked it and were making the music and benefiting from it were pretty much everyone but straight white guys. For the first time, minorities [sic] were really taking over the pop charts,” he explains. “It was the initial coming together of all that revolution at once, and I think it scared those who felt left out.”

DeCaro compares the event’s fanaticism to a MAGA rally. “It really was this toxic masculinity on display,” he says.

Current events aside, however, disco culture speaks about the need for happiness. “Somebody was telling me about some poll on songs that make people happy, and seven of the top 10 were disco songs,” says Hodges. “I think that has to do with what we’re talking about. It doesn’t really go away because it’s too full of energy and joy. You know, great art and food and music—they were created out of periods or people in some kind of strife: innovation comes out of pain and struggle. And I think disco is like that.”