- | 7:00 am

Inside Starling Lab, a moonshot project to preserve the world’s most important information

When the British army liberated the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in April 1945, they found horrors so shocking that a journalist’s eyewitness reports to the BCC were held for days because their veracity was in doubt.

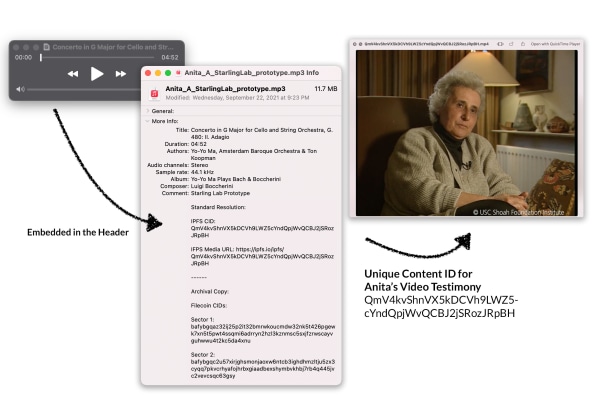

“We lived among heaps of bodies,” says Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, a survivor of the camp whose firsthand experience at both Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz is now memorialized in a 130-minute video testimony. In the 1998 video, she tells an interviewer from the USC Shoah Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the memories of genocide survivors, about how playing the cello in the Auschwitz orchestra helped her endure one of the most horrific atrocities in human history.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch [Screenshot: USC Shoah Foundation]

Lasker-Wallfisch’s recollections have now become the first test case for an ambitious project to preserve the foundation’s archive of 56,000 audio-visual testimonies through a radical means: the blockchain. While most oral histories are stored in more traditional ways—on hard drives, for example, or in the cloud—the digital file of Lasker-Wallfisch’s testimony is also being archived using a decentralized web protocol, creating extra redundancies in an effort to preserve her account on the internet for the long term. Right now, her testimony lives on dozens of different servers. One day, it may live on thousands.

[Image: Starling Lab]

The foundation’s move to the blockchain is in partnership with Starling Lab, a nonprofit academic research center that’s on a mission to use decentralized ledgers to help preserve historical data of importance to humanity. Its lofty goal is to restore integrity both to data and to the internet itself—starting with some of the most precious information we have.

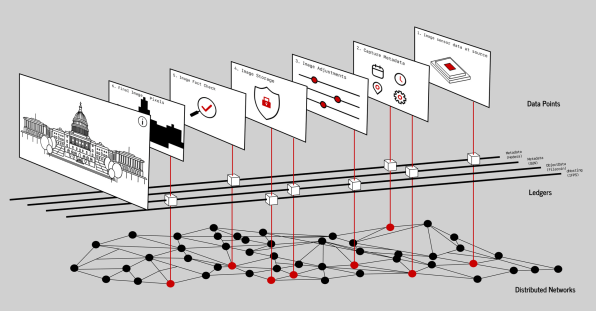

For the past three years, the lab’s founding director, Jonathan Dotan, has been developing a set of technologies, called the Starling Framework, that aims to maintain the integrity of a piece of information as it is captured and stored. Now, the lab is working with the USC Shoah Foundation to upload the nonprofit’s interviews from survivors and witnesses of 14 genocides and episodes of mass violence to a decentralized storage system. Each testimony is first checked to make sure the file’s data hasn’t degraded over its lifetime. It’s then given a unique content identifier—called a hash—that refers to both the image and its corresponding metadata, which includes where and when the testimony was taken. The storage system that Starling uses, called Filecoin, is built on a blockchain that requires data providers to constantly prove that they hold the same data that they were originally tasked with storing—ensuring that information hasn’t been tampered with.

Jonathan Dotan [Photo: Starling Lab]

A low-resolution copy of the foundation’s archive has already been uploaded to four Filecoin data providers. Starling and the foundation are currently in the midst of uploading a high-resolution copy to 20 storage providers—a 15-week-long process. (Starling and the foundation are also experimenting with how new testimonies can be embedded with a content ID and stored on the blockchain as they are filmed.)

The ultimate goal, says Dotan, is to help curb misinformation at a time when images are often used out of context to advance political and ideological agendas. But doing so requires more than building tech to facilitate the authentication and the storage of data. Starling is also creating an interface that allows third-party experts—lawyers, historians, forensic analysts, journalists, and more—to offer context and clarity about an image or video, creating what Dotan calls “a distributed form of consensus.”

“Capture, store, and verify—that’s critical in our minds to help create a proper chain of custody,” he says. And unlike other organizations that are working on similar ways to attach metadata to images, Starling, which operates between USC and Stanford, is academic, not-for-profit, and entirely open source. Its system doesn’t require a centralized entity to put a stamp of truth on any content.

Starling’s system can also be used to document the historical record in real time. In a Reuters pilot, the news service’s photographers used the lab’s technology to certify images of the 2020 presidential transition, even as its legitimacy was under attack. Starling has also built prototypes with Syrian human rights organization Hala Systems, which has been exploring how to use the lab’s so-called image provenance technology in court to present evidence of war crimes. Starling and Hala are currently working to encrypt, authenticate, and preserve social media content from Telegram and TikTok that documents the war in Ukraine.

But the project with the USC Shoah Foundation is Starling’s most significant demonstration of its technology yet. Ultimately, all 5 petabytes of the foundation’s archive, which contains 115,000 hours of video, will be stored in hundreds of places using the Starling Framework’s authentication. Stephen Smith, the foundation’s executive director, says this is particularly important at a time when disinformation campaigns seek to downplay the greatest horrors of our shared past. “The competition over history is very real,” he warns.

“It’s important that people identify with people when we talk about the Holocaust, because I always feel this idea of six million dead people is totally futile—there’s no concept of that,” Lasker-Wallfisch says near the end of her testimony. “I think these interviews are important for people to see that we were actually people, totally normal people, and nothing wrong with us, coming from totally normal families, being reduced to what we were reduced to, which led to this unprecedented mass murder.”

From Silicon Valley to Stanford

Starling Lab got its start in an unusual place: the set of the hit HBO TV show Silicon Valley.

Dotan has a record of straddling technology and entertainment. He started his career as a front-end engineer at a startup before becoming a mailroom assistant at a talent agency. He followed a stint at the Motion Picture Association with work as a private equity strategist before starting several software companies. His business partner on one failed startup introduced him to Silicon Valley creators Mike Judge and Alec Berg, who realized they could use the help of someone fluent in both tech and Hollywood and brought him on as a consultant. Dotan signed on as a full-time producer for Silicon Valley’s first season, tasked with ensuring that the technical story lines and references were accurate.

That season, Dotan says the writers began thinking about a meaningful application for the technology—a compression algorithm—invented by the show’s central character. Dotan learned about a project from the founders of BitTorrent, the peer-to-peer media distribution service famed for helping people share pirated audio and video. Its since-shuttered Project Maelstorm applied the same idea of peer-to-peer media sharing to a web browser. Dotan was intrigued: What if you could create a fully decentralized way to host a website, so you didn’t have to rely on commercial entities like Amazon Web Services? Could everyday users host the internet—just by using it?

It took the Silicon Valley writing team an additional few seasons to work this idea of a decentralized internet into the show’s plot. “We were writing scenes to explain why you would want this new internet,” he says. “We thought we wouldn’t convince people.” But then the 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal—when the public learned that a consulting firm had surreptitiously used Facebook data for political advertising—shattered the notion that the internet was inherently a force for good. The idea that we might want to start over with a brand new internet, a core theme in Silicon Valley’s final seasons, was suddenly a lot more compelling.

[Photo: courtesy of Jonathan Dotan]

The concept of decentralizing information stuck with Dotan, even as he stepped back from Silicon Valley and took a role at an augmented and virtual reality startup. Two of the show’s consultants, Stanford professors Tsachy Weissman and Dan Boneh, eventually convinced him to apply for a fellowship at the Stanford Blockchain Center. It was there that he hatched the idea for the research project that would become Starling Lab, with help from Weissman and Boneh.

“We realized that the Shoah Foundation’s archive was powerful and important to preserve and at the same time vulnerable,” Dotan says. “We got excited about the possibility of spreading it to thousands [if] not millions of different nodes. With more copies of the tech, it would be more resilient.” A Silicon Valley concept was taking a step toward reality.

A framework for trust

At its core, blockchain is a piece of technology that aims to use code alone to build trust. The most common and well-known application is in finance. Rather than needing a centralized institution, like a bank, to verify transactions, a piece of code sits in the middle. This is the mechanism that powers cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum: When someone sends a token to someone else, that transaction is recorded on a ledger that’s shared among a large number of distributed nodes. The sheer number of copies of the ledger make it hard to change or manipulate. The system is powered by an incentive structure in which people execute and verify the transactions by solving cryptographic challenges that earn them tokens in the system.

[Image: Starling Labs]

With the Starling Framework, Dotan is applying the same basic idea to storing information. “The idea is that end users could host a critical piece of data—be it a testimony of genocide or record of transaction,” he says. “The end result is that, paradoxically, the more that you spread out information and provide computation in a distributed fashion, the more trusted it could be.”

Dotan began the project in collaboration with the USC Shoah Foundation and Stanford’s department of electrical engineering in 2018, and brought on a few other consultants from Silicon Valley to help, including blockchain experts from Protocol Labs, the company that originally built Filecoin. With their help, Dotan began building out a framework that would address some of the challenges with trust online.

The proposition of an entirely decentralized “web3,” which widely refers to services that use blockchain-based technologies like cryptocurrencies and NFTs, has come under intense criticism as proponents run into scams, rug pulls, and other fraud. But unlike other web3 boosters, Dotan is clear that these technologies can’t create trust on their own. “We’ve tried to cut through the hype,” he says. “How can we have the people who are most affected by this technology—historians, journalists, lawyers—actually contribute to the development of the tech so it ends up being used for good?”

That’s why he has started hiring and partnering with experts across disciplines, including law, journalism, and human rights. The lab has brought on veteran journalist Ann Grimes, who worked at the Wall Street Journal and Washington Post and previously served as director of Stanford’s journalism grad program, and Sophia Jones, an editor and investigative reporter who has worked at The Fuller Project and HuffPost. These journalists will work with Starling’s newly announced class of journalism fellows to apply the Starling Framework as they document current events, from the homelessness crisis in the Bay Area to climate disinformation campaigns in Brazil. The lab also recently announced that Stanford law professor and human rights lawyer Beth Van Schaack was the founding chair of Starling’s law program, which plans to examine how digital evidence can be used to document war crimes. (She was just appointed to be President Biden’s Ambassador at large for Global Criminal Justice.) In addition, Dotan says the lab will partner with USC professor Allissa V. Richardson to document the work of photographers during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests.

The goal is to train others on how to use the tools so that organizations like the USC Shoah Foundation and Hala Systems can run their authentication systems without the lab’s technical help. “We don’t want to be the ledger of truth,” Dotan says. “That would be a crazy Orwellian result of this. We see ourselves as part of a benign ecosystem that can be continuously decentralized.”

How to make data last forever

The mission of an archival organization like the USC Shoah Foundation is to preserve information for as long as possible. Sam Gustman, the foundation’s CTO, hopes that the archive has a chance to become a supertext—information that’s so important to human history that it’s preserved through hundreds or thousands of years, like the Bible, the Quran, or Shakespeare’s plays.

But as the foundation has digitized its archive, it’s started to face an existential question: How do you store digital files for the long term? “As a general rule of thumb, the newer the tech, the faster it rots,” Gustman says. “It’s wonderful for tech companies so they can keep selling you stuff. It’s terrible if you want to keep your content around.” Film starts to show age-based damage when it’s 50 years old, and hard drives when they’re about five.

Casestudy stills [Image: Starling Labs]

The foundation’s move to the blockchain is the latest push in a robust preservation strategy. The nonprofit now has hard copies of the archive at USC and at data centers around the world. “In this context, decentralization just means creating a lot of replicas,” says Dan Boneh, the co-director of the Stanford Computer Security Lab who worked with Dotan on Starling’s cryptography.

The foundation also recently finished uploading a copy of the archive to Microsoft’s Azure cloud, a process that took about three months. However, executive director Smith says the organization has had bad experiences with commercial clouds in the past. A decade ago, the foundation started using a commercial cloud company that went out of business shortly after. “Our data just disappeared. The administrators just took the machines out, complete with our data,” says Smith. Today, he’s acutely aware that “the digital file itself is not there for life—it has to be cared for and looked after and preserved. There’s a great responsibility that comes with that.”

That’s where Protocol Labs, the company that created Filecoin, comes in. “[Data storage] infrastructure is really brittle. That’s not good, especially when we think about generational preservation of data, which has a huge role in defining our culture and our society,” says Pooja Shah, head of product at Protocol Labs. “It’s important that we create infrastructure that can last for hundreds of years, and [withstand] all sorts of government regimes and natural disasters.” The company also spun off the Filecoin Foundation for the Decentralized Web (FFDW), which supports open-source software and protocols that help to preserve information in a decentralized way. (Starling Lab is funded in part through a $2 million grant from the FFDW and Protocol Labs; Dotan says the funding did not require Starling to use Filecoin.)

Filecoin has unique properties that serve Protocol Labs’ lofty goals of long term, authenticated data preservation. A big part of that is Protocol Labs’ cryptographic technology, called Proof of Space Time. Essentially, every 24 hours, each storage provider within the Filecoin network has to do a new calculation that is only possible to complete if it has every piece of the data it says it’s storing.

Filecoin’s data storage network can also handle a lot of information. It currently holds 55.7 petabytes of data—and has 15.8 exabytes of supply (for context, estimates put the total number of words spoken by humans throughout history to be about 5 exabytes of data). The system is storing all kinds of information, from satellite images to a total of 48.5 million NFTs. It’s also used by the Internet Archive to store audiobooks and films that are in the public domain.

Shah says that the system is more energy efficient than other cryptocurrencies because it’s designed to reward usefulness: Providers that offer more storage to the system—and who are thus providing more useful services to the entire network—have a proportionately greater chance of mining Filecoin. This contrasts with the brute-force approach of Bitcoin and Ethereum, where computers compete to solve complex math problems on the off-chance they will win cryptocurrency. Because Filecoin storage providers earn rewards in the form of the Filecoin currency (worth roughly $19 at publication time) simply by doing the calculations to prove they still hold the data, they are able to cover all the costs of storage—and then some. That means it doesn’t cost the USC Shoah Foundation much to store its data. Dotan estimates that the reward system could cover about 20 years worth of storage for the archive, depending on the price of Filecoin.

Even so, the system relies on a cryptocurrency, which can be highly volatile. Ultimately, it’s part of a big experiment in decentralization. That’s why Starling Lab is just one of a host of ways that Shoah is storing its data. “In the event of a catastrophic failure of the internet, or blockchain,” says Smith, “there’s always that copy you’ve got buried in the mountains somewhere.”

Seeing is believing

Starling is also helping important information become part of the historical record, from Syria and Ukraine to Washington, DC.

The lab’s legal and development teams have partnered with the nonprofit Hala Systems to implement in Ukraine the open-source tools that the two organizations previously developed to document war crimes in Syria. The team has reserved 2 petabytes of decentralized data storage in the Filecoin system, and is working to authenticate and safeguard content from social media platforms like Telegram and TikTok, news sites, and messaging platforms, such as Signal and Slack. “Our goal is to move quickly to safely preserve the evidence [of war crimes] and increase the chances it can be admissible in accountability proceedings in international and domestic courts,” Dotan says.

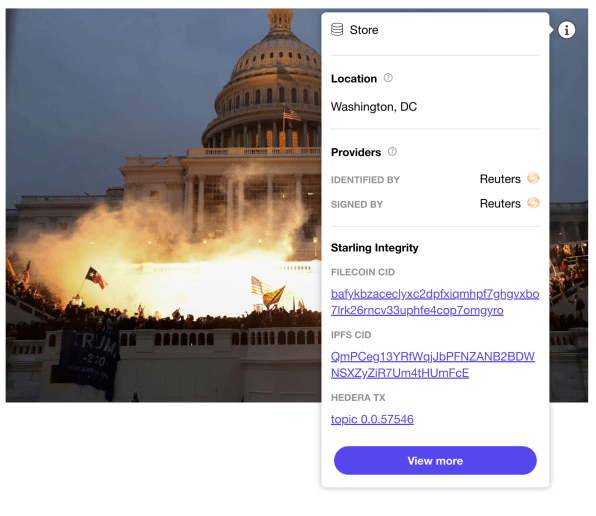

The lab has also worked directly with journalists. From November 4th, 2020 until January 20, 2021, Reuters photographers used Starling’s authentication technology to embed metadata within more than 200 photos taken during the presidential transition from Donald Trump to Joe Biden, including the January 6 attack on the Capitol. Today, each image in Reuters’s 78 Days archive has a small “i” icon in its top right corner; once you click, you can see a host of information about the image, including the location where it was taken, the photographer’s name, the Filecoin identifier, and the general content ID number, called IPFS. Clicking on “view more” takes you to a website called Verify, a tool that enables you to see all the metadata embedded in each photograph. The site, which is still in beta, is hosted by the Content Authenticity Initiative, an Adobe-led project to add metadata and blockchain-based verification to images.

[Image: Starling Labs]

The importance of the Reuters project is encapsulated by the controversy over two images that the news organization published back in January 2017—one showing the National Mall on the day of Obama’s first inauguration, and the second showing the same location during Trump’s. Trump’s inauguration looked barely attended in contrast, setting off a media firestorm. Trump fired back in his first speech in office, with then Press Secretary Sean Spicer continuing the attack by insinuating that Reuters had manipulated the images. At the time, there was no blockchain-backed metadata to prove otherwise. Ultimately, the controversy sparked the now-infamous phrase, “alternative facts,” coined by Kellyanne Conway.

“No one could have predicted that Spicer’s first press briefing attacking the veracity of the photos of inauguration crowds would culminate with a violent assault on the U.S. Capitol four years later, but the two events share a dangerous line of thinking,” Dotan and Stanford professor and journalist Cheryl Philips wrote when the 78 Days archive launched in 2021. “They demonstrate how the authenticity of photography is critical for the credibility of journalism, and how the absence of it can lead to chaos.”

[Image: Starling Lab]

On January 6, 2021, Reuters journalists used Starling’s content-capture app to photograph and authenticate images depicting rioters, including the now infamous QAnon Shaman, storming the Capitol building, pushing down barricades, overwhelming the police, and waltzing into the building’s inner sanctum. “It’s as close as we’ve got so far to documenting a major historical event [that] may be disputed and having a source file that is not disputable,” Smith says. Reuters is now exploring how to apply Starling’s technology to its editorial process in a sustainable way.

None of this technology, however, has stopped the conspiracy theories that it was antifa, not Trump supporters, who stormed the Capitol; nor has it prevented Republican lawmakers from playing down what happened that day. As older technologies continue to enable the splintering of our shared reality, new technologies promise no quick fix. But the proof is there in the code, for anyone who cares to look.