- | 9:00 am

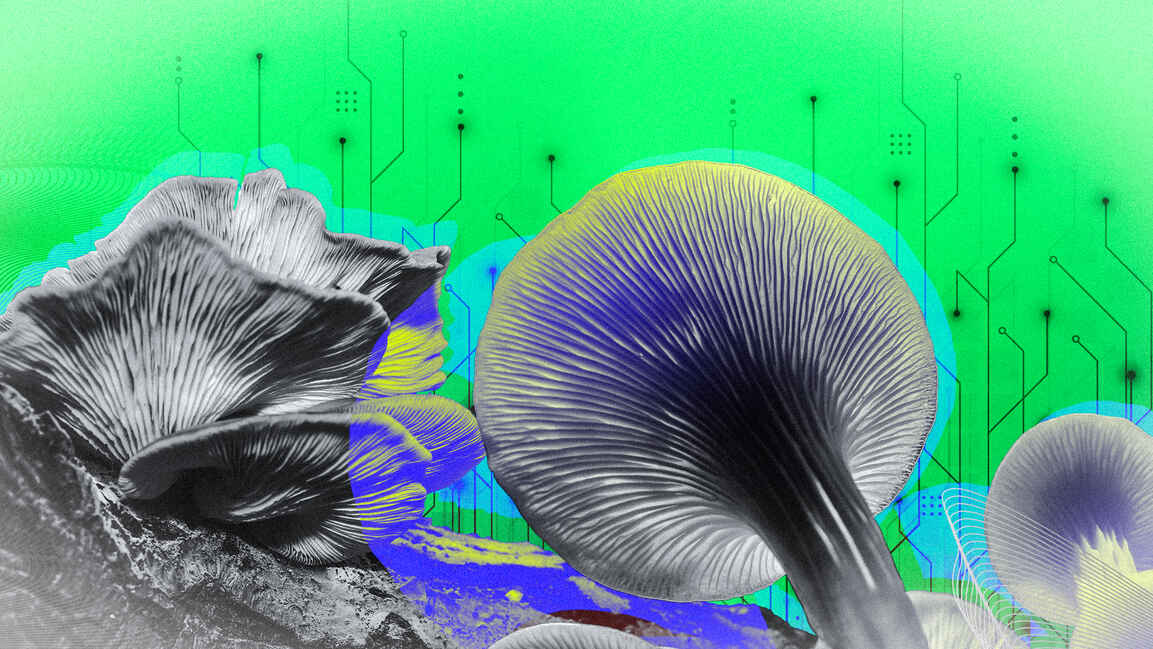

How fungi are disrupting the Middle East’s tech-driven sustainability goals

In the harshest environments, nature’s quietest organisms may be the ones rewriting the rules of innovation.

In the Middle East’s relentless deserts, where temperatures soar and soil turns to dust, the future of sustainability may be lying just beneath the surface, woven through the hidden threads of fungi.

From regenerating soil to building biodegradable shelters, desert-adapted fungi are emerging as a radical new frontier in the fight against climate collapse. And while they lack the headline-grabbing appeal of AI or space tech, their potential promises to transform everything from conservation strategies to construction methods could be just as profound.

A KINGDOM LONG OVERLOOKED

“Fungi aren’t usually top of mind in the climate tech space,” says Liliana Slowinska, cofounder and managing director of Below Farm, a UAE-based startup focused on desert mushroom cultivation. “They’re small, ephemeral, and not audacious like animals or as visually appealing as plants. But they are an entire kingdom that connects everything.”

Despite this invisibility, fungi have become central to a new wave of regional innovation. “We should all be one fungal movement,” she says. “Because that’s what fungi do—they connect systems.”

Desert fungi are being studied for their role in climate mitigation, particularly their ability to sequester carbon in drylands, which cover nearly 40% of the Earth’s surface. Unlike forests, which are vulnerable to wildfires and deforestation, arid soils enriched with fungi may offer a more stable and scalable form of carbon storage.

LIVING INFRASTRUCTURES FOR THE DESERT

Few people understand the transformational potential of fungi more deeply than Dima Al Srouri, founder of MycoSphere, a UAE-based startup pioneering fungi-based materials and biotechnologies for the built environment.

“When I first started working with fungi, I asked: How are we going to grow fungi on local material when we don’t have forests?” she recalls. “Every species is associated with specific trees. So in the desert, we had to rethink everything—look at our waste, look at the fungi we do have, and ask, what’s possible here?”

The answer, it turned out, was extensive.

To build materials with mycelium—the dense root system of fungi—Al Srouri experimented with dozens of species. The ultimate breakthrough came with Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi), a global superstar in fungal biomaterials thanks to its high content of chitosan, a molecule that gives it strength and durability. “But Reishi is associated with hardwood trees, which we don’t have,” she says. “So we had to hack the fungus to accept palm—our regional tree of life.”

It took years of trial and error, but MycoSphere developed fungal materials based on date palm waste that could match or exceed synthetic alternatives in strength, all without harmful chemicals.

And the research continues. “We’ll never stop iterating,” Al Srouri says. “Every batch teaches us more about how our local environment can work with global fungi.”

THE CHARISMA GAP IN CONSERVATION

While entrepreneurs like Al Srouri and Slowinska are building fungi into food and material systems, others are battling for fungi’s rightful place in conservation strategy.

“In terms of species survival, fungi are still nearly invisible,” says Georgina Pereira, Manager of Species Survival at Terra, a UAE-based sustainability center. “In the Middle East and West Asia, fewer than 100 fungal species have been formally assessed. But the irony is—over 90% of our plants grow because of their mycorrhizal relationships with fungi.”

The problem? Fungi aren’t charismatic. “Conservation funding is dominated by megafauna—lions, tigers, elephants,” Pereira says. “But fungi? They get about 0.2% of global conservation funding. And that’s combined with algae.”

This “charisma gap” is not just about visibility; it’s about public connection. “People protect what they feel connected to,” she says. “That’s why at Terra we focus heavily on community engagement—citizen science walks, student workshops, bioblitzes—so people start seeing fungi as part of their daily story.”

The center is also home to the world’s only desert-focused fungal database, providing a global research hub for understudied species in arid ecosystems.

ETHNOMYCOLOGY AND CULTURAL KINSHIP

Pereira believes the GCC has a unique opportunity to lead a new kind of conservation—one rooted in culture as much as science. “When we talk about fungi here, we’re not just talking about spores and mycelium. We’re talking about ethnomycology—the cultural and medicinal relationships people have had with desert fungi for centuries.”

Take the desert truffle (Terfezia), prized by Bedouin communities and only found growing in association with the rock rose (Helianthemum). “You can’t grow the truffle without the plant,” she says. “And you can’t grow the plant well without understanding its fungal relationship. It’s an exquisite example of symbiosis in extreme conditions.”

Another example? The UAE’s ghaf tree, whose health can be monitored through fungal indicators like Ganoderma. “When these mushrooms appear, it tells you the tree might be waterlogged or stressed,” Pereira says. “That kind of ecological feedback system is gold—if you know how to read it.”

This interconnectedness is more than academic—it’s practical. “If we want native flora to thrive, animals return, pollinators increase, and ecosystems recover. And it all starts with what’s underground.”

FUNGI FOR HUMANTITY

But fungi aren’t just the unsung heroes of nature. They may also be key to humanitarian resilience. Al Srouri’s ReRoot project explores how fungi-based shelters could provide sustainable housing for displaced people, while also healing war-torn soils.

“When we rebuild after conflict, no one talks about the soil,” she says. “What if we could create a housing unit that decomposes into the earth—and helps remediate it?”

The idea is radical yet elegant: grow mycelium-based shelters from local waste, deploy them quickly, and let them return to nature when no longer needed. “Even if the unit doesn’t fully remediate the land,” she says, “we can give people a grow kit to help regenerate soil beside their home. And over time, you rebuild ecosystems. From a small mycelial network, a community can grow.”

SCALING SLOWLY

Still, no one pretends this will be easy. “Biology doesn’t scale like software,” Slowinska says. “You can’t force mushrooms to grow faster—they grow at their own pace. But that slowness is part of the power. You’re working with biology, not against it.”

Cost remains another barrier. “Natural materials are more expensive,” Al Srouri admits. “And the temptation is always there to cut corners with synthetic additives. But then you lose the very thing that makes it sustainable. We’ve chosen a slower path—because it’s the right one.”

While fungi may still be underfunded and underrecognized, the momentum is shifting. From food security to carbon sinks, from cultural heritage to climate adaptation, fungi offer a model of resilience and regeneration uniquely suited to the Middle East’s challenges.

“We always say: it’s not nature for nature’s sake,” Pereira says. “It’s nature for people’s sake. And fungi are the link. They’re the bridge between survival and sustainability.”

In a region known for extremes—heat, drought, and ambition—it’s the smallest organisms that may soon make the biggest impact.

Because in a world obsessed with disruption, fungi remind us that true change grows slowly, invisibly—thread by thread, root by root.