- | 8:00 am

A new generation of magazines is getting kids to put down their phones

In a world of smartphones and screen time, parents are willing to pay for high quality magazines for kids. It’s reviving a once dead industry.

On a recent Saturday afternoon, I noticed an unusual silence from my 9-year-old’s room. I was surprised to find she wasn’t taking advantage of her allotted two hours of screen time; instead, she was curled up on her chair reading a magazine.

Three decades ago, when I was her age, this wouldn’t have seemed strange. Starting in the late 1800s, the United States had a thriving culture around children’s magazines. Young children would get Jack and Jill, Turtle, or Sesame Street Magazine in the mail; teens would graduate to Sassy, Tiger Beat, or Teen People. But as the internet emerged—with blogs, streaming sites, and online games competing for young people’s attention—magazines lost their luster. Although there are a few legacy magazines that still publish, like Sports Illustrated Kids, National Geographic Kids, and Highlights, most have gone out of business over the past 15 years.

In a strange twist, however, kids’ magazines are making a comeback thanks to a new flock of startups. My daughter, for instance, was pouring over Anyway, a magazine for 9- to 14-year-olds that debuted in 2023. Jen Swetzoff and Keeley McNamara launched the magazine with a Kickstarter campaign to see whether there was an appetite for a publication that deals with the issues tweens are facing, from understanding body hair to developing personal style. The founders reached their funding goal within days, and hundreds of families now receive their quarterly magazine.

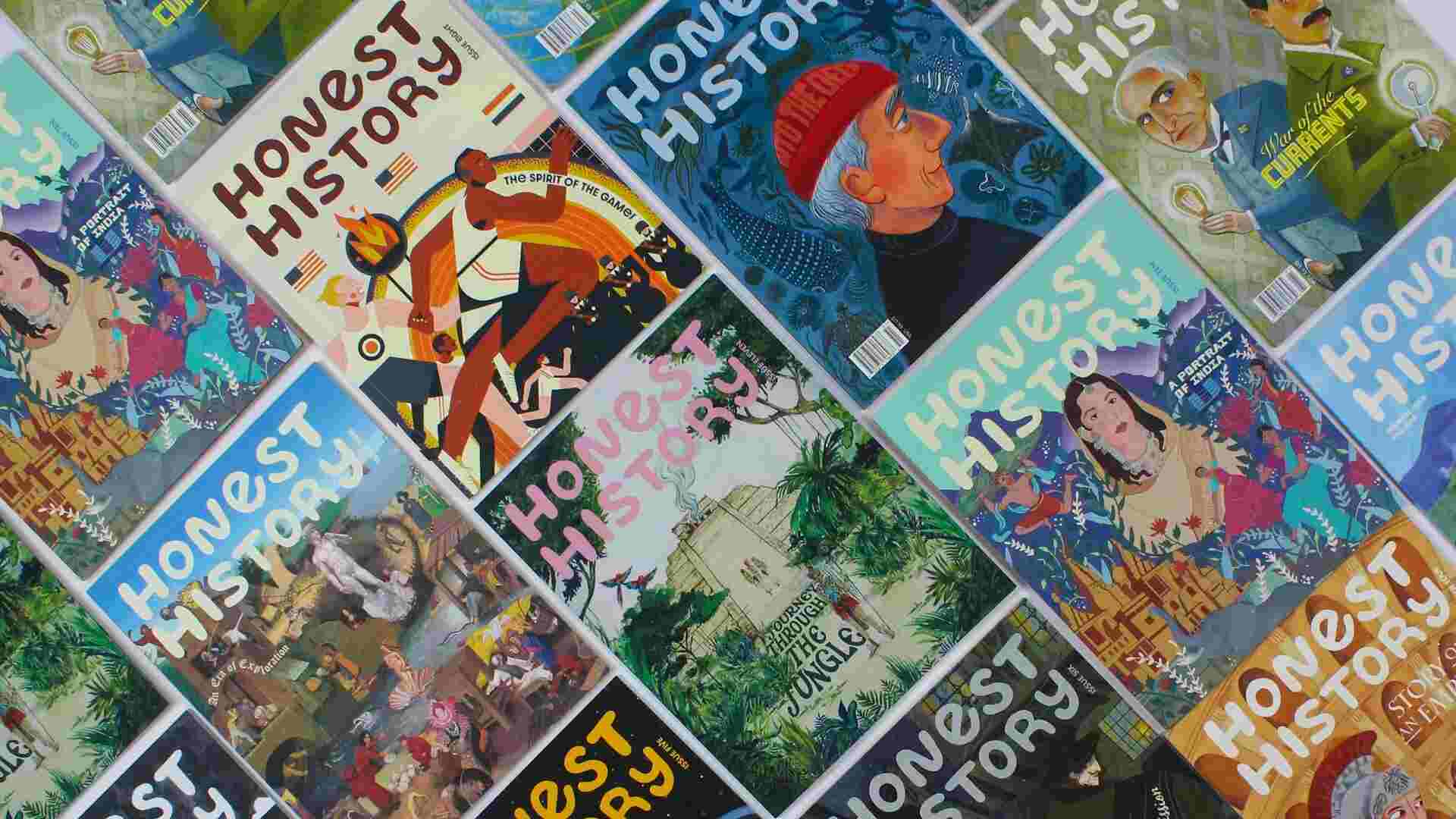

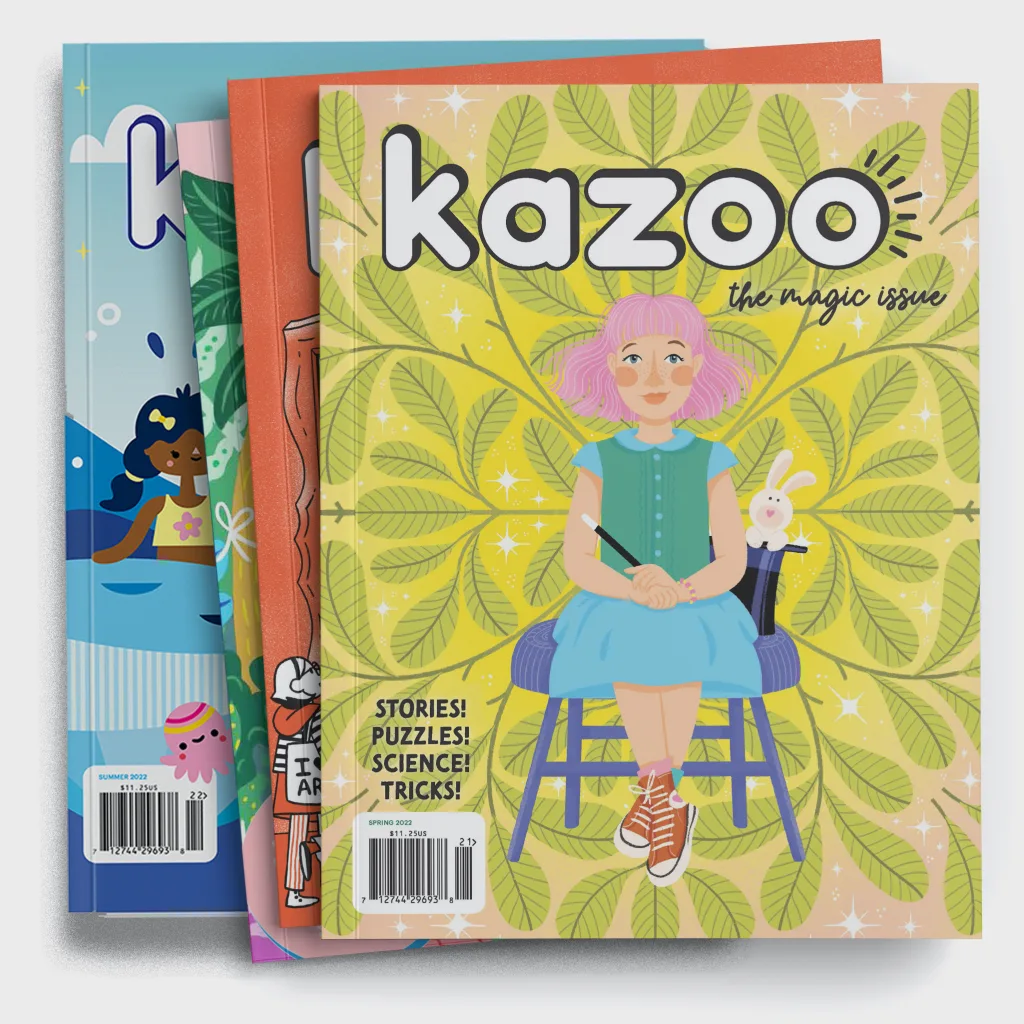

Anyway is part of a broader wave of new publications that began nearly a decade ago with Kazoo, a quarterly magazine for 5- to 12-year-old girls that features contributors like Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Jane Goodall, and has won a slate of awards. There’s Honest History, which makes history engaging to elementary school kids. And Illustoria, a kid’s magazine for children up to 14, meant to encourage creativity and imagination. One of the more recent entries is Spark, a monthly activity magazine for kids between 4 and 8.

According to these magazines’ founders, their publications are growing not in spite of smartphone culture, but because of it. As it becomes clear that too much screen time can be harmful to children, parents are willing to spend money on print magazines because they provide an alternative to technology. And this new world of kids’ magazines raises the interesting possibility that today’s children who grow up with print publications may continue to seek them out as they get older.

An Ad-Free Business Model

Erin Bried, founder of Kazoo, had spent her entire career in magazines, as an editor at Self and Glamour. She’d seen the industry collapse as advertising revenue dried up and people stopped buying print magazines. Despite this, she believed there was a market for a magazine for young girls that inspired them to be smart and strong. “I would take my daughters to the magazine rack and there really wasn’t anything they were interested in,” Bried says. “It occurred to me that I could create it.”

Bried quit her job to focus entirely on Kazoo. She began with a Kickstarter campaign to see if there was any appetite for the kind of magazine she had in mind, featuring stories by top children’s authors, interviews with heroines like Sonia Sotomayor and Misty Copeland, and comics. She raised an astounding $171,215 — the highest figure for a magazine. Nine years later, the magazine has tens of thousands of subscribers who pay $58 a year, and every year the circulation grows. It’s the only children’s magazine that has won a National Magazine Award for General Excellence.

For Bried, it was crucial not to rely on advertising. She had seen how quickly advertisers had pulled out of magazines when they realized they could reach people more directly on social media and Google. But also, having direct subscribers gives Bried more control over her company. “At so many magazines, you were reliant on ad dollars, clicks, and algorithms,” she says. “You were reliant on outside forces and never had total control over your own success. We aren’t in that situation.”

While Kazoo is profitable, its budget is much smaller than those of kid’s magazines of the past. Bried has made the business work by doing most of the work herself. She writes most of the copy, assigns fiction stories and comics, and hires illustrators. “I only bring on female creators, given the focus of the magazine, and I make sure to pay them well,” she says. “But you cannot imagine how much work I personally put into each issue.” (For instance, she deals with customer service issues, which means walking to the post box to send off issues that got lost in the mail.)

It’s a similar story at the other magazines, which all rely on subscribers. The founders run a very tight ship, doing most of the work themselves, tapping on freelance artists and writers. And most are profitable. Sparks, founded by Katie and Cody Gibbs, is already in the black after one year, at a price of between $6.50 and $8.75 a month, depending on the length of the subscription. “We didn’t want it to be cost prohibitive,” Katie says. “But we’re grateful to be profitable so quickly.”

Beautiful Immersive Art Objects

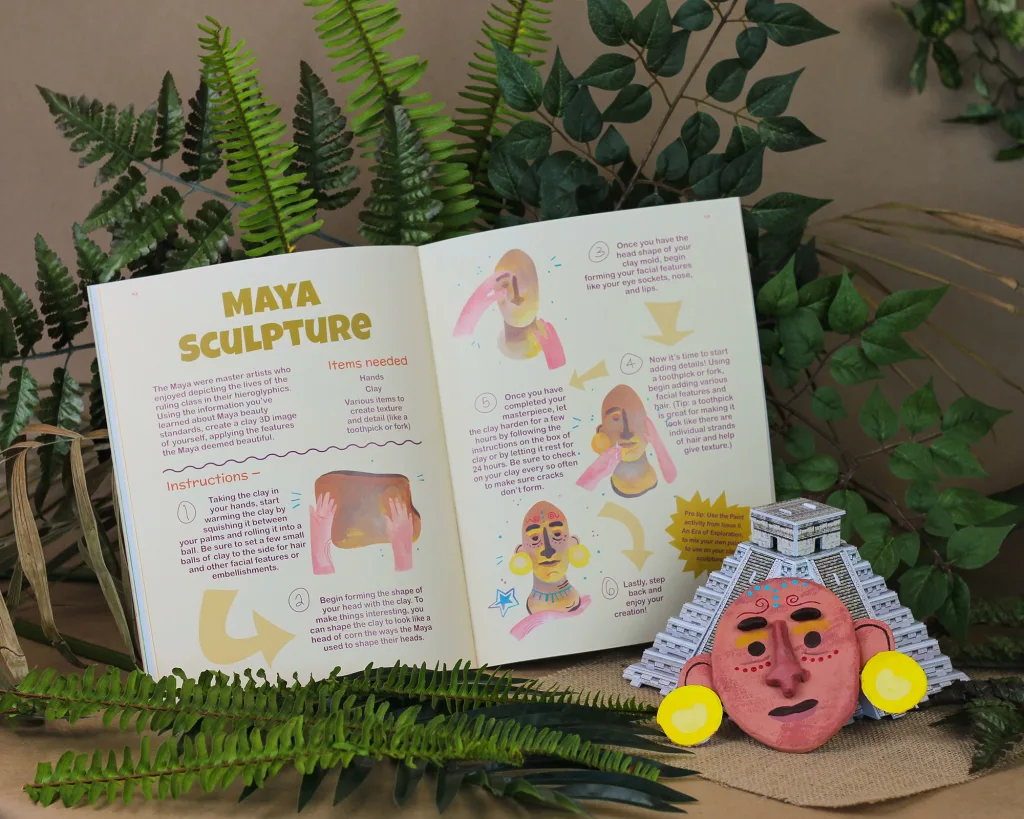

Given that these magazines are competing with the visual appeal of screens, the founders have worked to make them aesthetically appealing. Their covers are beautiful, featuring stunning, immersive art and very little text. Honest History‘s cover this moth features a retro-modern image of robots, circuits, and clocks to reflect the issue’s focus on the history of technology. Anyway‘s features stunning photography of a female skateboarder in mid air. They’re very different from the magazines of the ’80s and ’90s that tended to have crowded covers packed with text advertising the content inside.

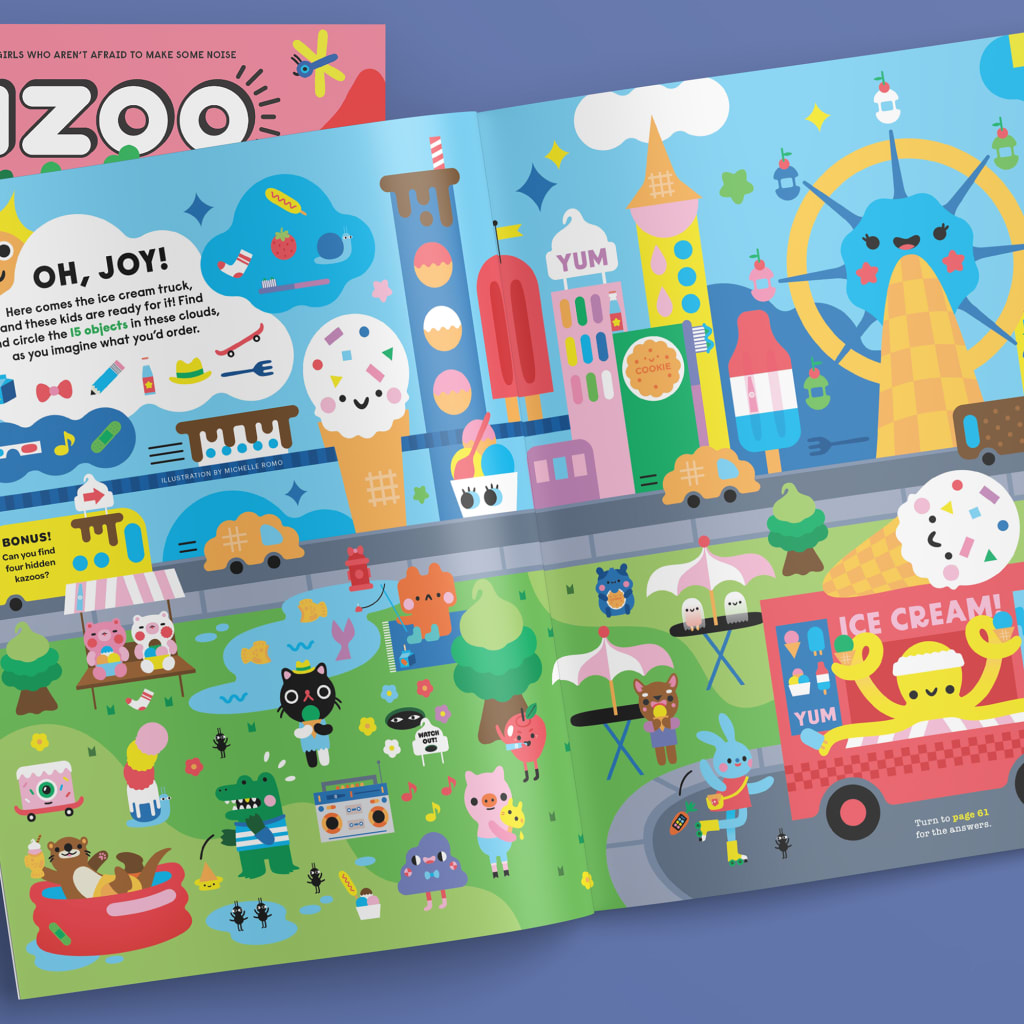

While Katie Gibbs creates the content and puzzles in Spark, she partners with a design agency called Whiteboard that creates all of the illustrations. The magazine has a very clean aesthetic and consistent visual branding. There’s a lot of white space, a soft color palette, and some hand-drawn illustrations in the midst of the graphic design.

In the past, consumers thought of magazines as disposable. But given that today’s consumers aren’t used to spending money on magazines, Honest History’s cofounder David Knight felt that it was important to deliver a product that felt more like a book or an art object that families would keep coming back to. “When people are spending between $12 and $15 an issue, they’re more intentional about the purchase, and they’re looking to buy something that feels permanent,” he says.

This influences how these magazines tackle content. While kids’ periodicals used to focus on current events, today’s magazines tend to focus on topics that tend to be more evergreen. “We’re trying to stay plugged into the issues kid’s care about today, but we’re always thinking about whether a reader will find this interesting a few months, or years from now,” says Anyway‘s Swetzoff.

An alternative to screen time

Gen Z, who are now between 13 and 28, were the first cohort to grow up in a world of smartphones, social media, and video streaming. For years, it was unclear how this technology would impact them, but there’s now a growing body of data suggesting that it is problematic. A new meta-analysis of research suggested that children who spent a significant time on screens were more likely to develop socio-emotional problems. And a study by Gallup found that Gen Z reports the poorest mental health of any generation.

As parents of tweens, Swetzoff and McNamara were alarmed by all of this data. They scrambled to find ways to help their kids navigate technology and develop strategies for coping with emotional challenges. A print magazine seemed like a smart solution. “When we first had the idea for coming up with a magazine for teens, some parents asked why it had to be on paper, when it could so easily be online,” Swetzoff says. “But then, more data began to emerge about the impact of digital media on our kids, and we saw a shift. Parents really understood the value of having a print magazine.”

Anyway addresses some mental health issues directly. In the most recent issue, for instance, there’s a whole section about why sleep is important and how tweens can get better quality sleep. It’s also full of ideas for fun activities that don’t involve screens, like cooking and flower arranging.

Parents of younger kids are eager to avoid the pitfalls of the previous generation. Spark is specifically designed to give 4- to-8-year-olds an alternative to screen time. It’s full of old fashioned puzzles and activities, like mazes, spot the difference pictures, and color by number. “A big theme throughout our magazine is slowing down and noticing things,” she says. “We’re encouraging kids to look closely at the art. Can you find the flashlight somewhere in this camping scene?”

Honest History is on a similar mission. “There’s something inherently calming and regulating about giving children something they can sit down with and encouraging them to look carefully at pictures,” says cofounder Brooke Knight. “It encourages better focus and learning, as opposed to a screen where they have images flashing at them.”

In an ironic twist, while technology killed the last generation of kid’s magazines, it is also technology that appears to be breathing life back into this business. Today’s parents seem willing to spend money on engaging and educational magazines, if it will get them away from shows and social media and video games. “We’re seeing kids fall in love with magazines again,” says Swetzoff. “It’ll be interesting to see if they keep seeking out magazines as they get older. There’s a chance the magazine industry will make a comeback.”