- | 9:00 am

Rocket Lab CEO on the new space race: ‘It’s getting exciting’

Peter Beck, founder and CEO of the publicly traded, $23 billion space company, on his highly anticipated Neutron rocket, getting launches right the first time, his Golden Dome ambitions, and Rocket Lab’s ‘distinct advantage’ over rivals.

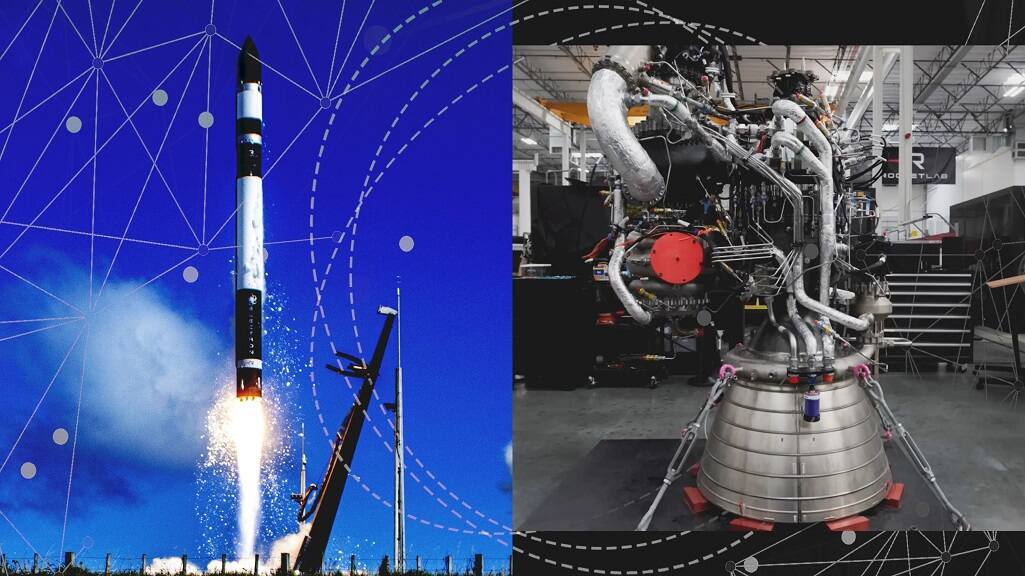

Rocket Lab’s pivot from small launch darling to serious SpaceX competitor is about to be tested. The Long Beach, California-based company has already sent 12 of its light-lift Electron rockets into space in 2025, carrying payloads for commercial and government customers, with several more planned before the end of the year from its Virginia and New Zealand launch sites.

But the next several months are pivotal, as Rocket Lab races to bring its next-generation, medium-lift Neutron rocket to the launchpad before year’s end. It’s an ambitious timeline, CEO Peter Beck acknowledges, and the company will need to hit all its marks in the coming weeks to meet it.

“When we put a vehicle on the pad, we do not expect it to fail,” Beck tells me in our wide-ranging conversation. “If you look at our launch vehicle, our spacecraft history, generally the stuff that we build works the first time.”

But with the success of Neutron, Rocket Lab will be able stake its claim as a major player in space-defense infrastructure. Neutron can carry nearly 28,000 pounds, perfect for launching larger satellite constellations and national security missions. Already, Rocket Lab is building satellites for missile defense systems, broadband, and more.

As he prepares for the first flight of Neutron, Beck talked with me about what’s riding on this next-gen vehicle, how the company’s long-term strategy hinges on making it work, and why launchpad explosions are not part of his development plan.

We’ve seen mixed outcomes among your launch competitors this year, with some notable flameouts. How do you see the state of competition right now?

I think everybody can declare that the small-launch race has been won, right? Electron has really hit a high cadence this year, and we’ve had a lot of customers all turning up on time, which is fantastic.

I remember when we started the Electron [program], there were more than 100 small launch companies and billions of dollars flowed into small-launch. Astra consumed $400 million or so in their program [before going private last year and refocusing on engine building]. Virgin Orbit spent $1.2 billion on their program [before filing for Chapter 11]. ABL spent $300 million or $400 million, and so it goes. Firefly is sending payloads into the ocean.

I think the medium-launch market is going to end up in a similar way. There are a few programs that are funded, and I think that will sort itself out and there will be a viable alternative to the [Space X] Falcon 9, which is much needed for some competition in that space.

It’s going to be really interesting as the heavy vehicles shake out. You saw a really great flight from [United Launch Alliance’s] Vulcan. You’ve got [Blue Origin’s] New Glenn coming on. So it’s getting exciting.

The next phase of Rocket Lab’s business depends on getting the medium-lift Neutron launched. You’re still holding out hope for a launch in 2025?

Things are happening in parallel and they’ll all sort of crescendo at the end. It’s a “green light” schedule—that means everything has to go. But right now, we can see a path until there’s no path. We’re not waving the white flag.

And at the end of the day, if it’s not at the end of the year, it won’t be that far away. A few months here or there in the grand context of a 20-year lifecycle of a product is just totally irrelevant.

Courtesy of Rocket Lab]

One of the things that I don’t think we’ve done a good job of is putting into context that this will be a four-year-plus, $350 million rocket development program. If you look at the last two rocket development programs: The one that just launched [ULA’s Vulcan launch], that was a decade and $7 billion. And another one that just launched [Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket] was, like, 20 years and nobody knows how many billions of dollars.

In space exploration, things go wrong all the time. If the first Neutron launch fails—if it explodes as we’ve seen from competitor rockets—are you ready to try again quickly?

Let’s talk about philosophy to start with. So, we don’t put anything on the pad unless we think it’s going to work. The threshold for Electron was 92%: I said to everybody that unless you are 92% sure that your system is going to be perfectly functional, don’t put it on the pad.

Other companies have philosophies where they’ll take big risks and are happy to fail and fail fast. I think you can do that if you have essentially infinite capital.

Our development approach is not like that. When we put a vehicle on the pad, we do not expect it to fail. If you look at our launch vehicle, our spacecraft history, generally the stuff that we build works the first time.

The expectation of Neutron is that we reach orbit on the first flight. I’m not setting an expectation that we clear the pad, or that we get a good stage burn or nominate so many seconds of flight—that’s all bullshit. The idea here is to get to orbit.

The one area I would appreciate people giving us some slack on is the reentry and landing, because that’s new and it took a company a very long time to master.

But if the worst happens, we have enough capital reserves to fund the entire program three times over. So it would be disappointing. Someone would need to leave me alone for a couple of days. But it presents no existential threat to the company whatsoever.

How quickly can you establish the kind of regular launch cadence you now have with Electron?

At the moment, there’s one Electron rolling off the line every 11 days. With the Neutron, we’ve been really consistent that our bill rate will be one, three, and five [for the first three years].

Although everybody wants it to be faster, that’s what it takes. You need that dwell time between those flights to make the upgrades and the learnings that you see and to build that into your manufacturing.

With Electron, we put a factory in that was capable of producing one Electron every week, and we are at one every 11 days now. We haven’t bought or added any capital equipment. We followed the exact same approach with Neutron.

Courtesy of Rocket Lab]

At our Middle River, [Maryland] facility, we invested in a 90-ton, three-story building where we build all of the composite components for the vehicle. We have the Archimedes engine factory, in Virgin Orbit’s old factory building [in Long Beach, California]. So we’re able to really build that scale quickly.

The one wrinkle here with Neutron is that it’s a reusable first stage. So the highest production rate we will ever have of stage ones at least is at the beginning of the program. And then stage ones get replaced once every 10 or 20 flights.

Launch services are just one part of Rocket Lab’s business. Where do the others stand right now?

On the space-system [spacecraft components] side, we continue to build out scale there with pending acquisitions of companies like Mynaric [a German manufacturer of laser communication equipment], which are a really key element.

And the third pillar is you’ve seen us for the first time move into payloads, which is squarely focused on national security. We think with the opportunities that are there right now, that is exactly the right place to be focused.

Can you explain what you mean by “payloads”?

The sensor. Basically, you only build a satellite to host the sensor. The sensor is doing the work, and you only launch a satellite because you need to put the sensor in orbit. So, everything revolves around the sensor, whether it’s an antenna for doing broadband or it’s a telescope for doing Earth observation, it is the reason that you build something and go to space.

And that’s the reason for acquiring Geost, which makes electro-optical and infrared sensor systems?

The acquisition of Geost positions us to be a disruptive player in [defense] programs such as the Golden Dome. It’s not quite the Manhattan Project, but not that far off, with massive spending. And the space domain piece of that is core.

Our aspirations are slightly larger than just to be a part of it. We want to be a real provider. And the payload, or sensor, acquisition of Geost is a key element for that missile defense infrastructure that we now have under our belt.

With the continuing uncertainty around the Ukraine conflict and U.S. involvement with NATO, have you had more demand from governments in Europe, too?

With the world today, unfortunately, everybody is looking at their defense strategy. I’d say we are just getting our feet in Europe. Obviously, we’ve won some launch contracts for the European Space Agency on Electron, and our components business has sold into Europe for a long time. But once we close the acquisition of Mynaric, we’ll have a German base. If you look at how we’ve expanded globally, Europe is the next big opportunity for us outside America.

Have changes in government contracting under the Trump administration, and the DOGE cuts, impacted your business? Have you benefited from the Trump-Musk falling out?

I have a policy not to comment on politics. Unlike my competitor, I’m just a humble rocket guy. But what I will say is that there is more desire than ever to have a really fulfilled competitive landscape within launch especially. Both commercial customers and government customers really want Neutron to come along and provide some competition in a market that has become a little bit less competitive over time.

Courtesy of Rocket Lab]

Do you think the space industry will look very different five years from now?

If I have my way, it will. I think it’s going to become very clear, if it’s not already, that the really large space companies of the future are going to be a little bit blurry about how much of a space company they are and how much of a something-else company they are.

I mean, if we look at our friends over at SpaceX, are they a telecommunications company, or are they a space company?

It has always been our ethos and our belief that if you have the ability to build the spacecraft and launch it and deploy it in orbit at a rate that’s faster than anybody else, then you have a distinct advantage.

That’s been proven out with Starlink. The only way to be competitive with Starlink is to have your own ability to launch at will, at mass, at cadence, your own satellites. I think that will become true in a lot of domains in space.

And so there’ll be a relatively small number of companies that have launch and manufacturing capabilities who will be the large players.

Does that mean that many of your current competitors will not be around in five years?

I don’t know if they’re still around, or they morph, they adapt? That’s up to them. As the industry changes and adapts, you can have your Kodak moment or not, right?