- | 8:00 am

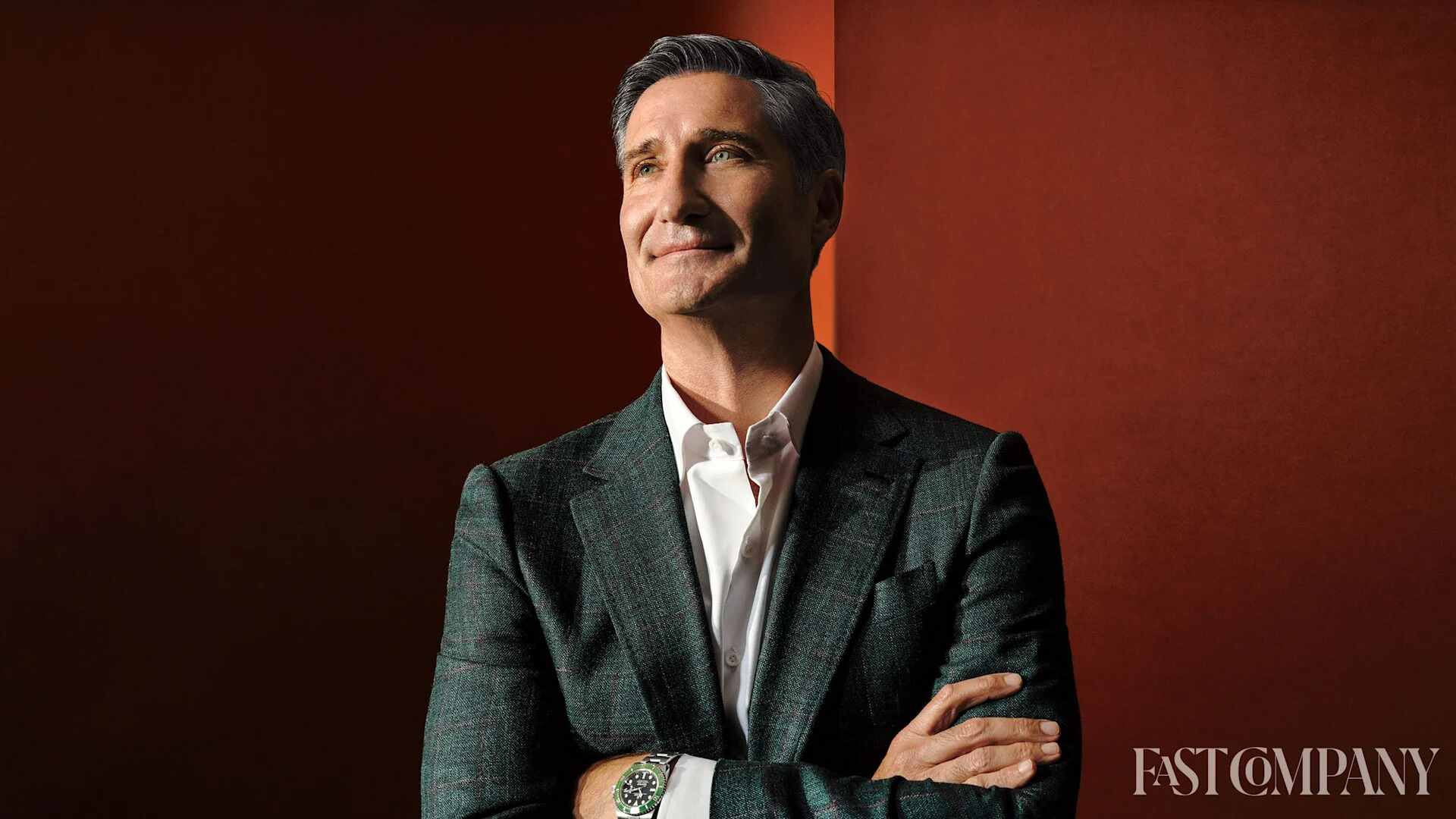

Inside Brian Niccol’s bold Starbucks redesign

Starbucks’ star CEO has spent the past year trying to turn coffeehouses into living rooms, reduce app overload and barista burnout, and restore the company’s soul. All while kickstarting growth! How long are customers and Wall Street willing to wait?

You’d think it would smell like coffee. Instead, there’s a faint whiff of livestock in the air.

For the past hour and a half, some 14,000 Starbucks store managers have been streaming into the Thomas & Mack Center on the campus of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, filling the arena. Even though it’s only noon on this June day, the music is pumping and people are dancing under purple lights. Some start a wave, which ripples through the crowd.

In just a few hours, they’ll sample the company’s new 1971 Roast from their seats, in what has to be one of the world’s largest coffee tastings ever staged. But even the scent of those dark-roast beans can’t erase the barnyard aroma from the years of rodeos that have been held in the arena.

This three-day Las Vegas extravaganza, known as the Starbucks Leadership Experience, marks the company’s first such event since 2019, and the excitement is high, particularly since Brian Niccol is about to give his first major address since becoming CEO last September.

Lil Jon’s “Get Low” rumbles through the arena as Niccol makes his way past the crowd, shaking hands and posing for selfies like he’s running for office. Soon, he takes the stage to loud applause and quickly begins laying out his vision for returning the company to its 2010s heyday, when Starbucks’s stores were known as comforting coffeehouses and its stock was on a steady climb.

Niccol has been giving a version of this talk—pitching what he calls his Back to Starbucks plan—to investors and analysts for the past several months. Now, he’s facing his employees.

“Look, we’re here for a simple reason,” he says, surveying the audience. “Okay, a really simple reason. Our future success depends on all of you in this room.”

That may be true, but as Niccol well knows, much of it rests on his shoulders.

When Starbucks recruited Niccol from Chipotle, it appointed him both chairman and CEO and offered him nearly $100 million, including stock awards and a cash bonus, for the first four months alone on the job. (Going forward, he’s eligible for at least $24 million annually in equity and pay, a third more than McDonald’s CEO Chris Kempczinski received in 2024.)

It also offered him access to the corporate jet for commuting between his home in Newport Beach, California, and Starbucks’s headquarters in Seattle. (He has since acquired a local residence.) It’s an extraordinary pay package that bets heavily on Niccol’s ability to pull the iconic coffee chain out of an unprecedented slump.

After decades of stamping its siren across the globe, Starbucks’s reign as the world’s leading coffee company is faltering. Its global dominance—roughly 41,000 stores worldwide—is being threatened by the Chinese chain Luckin, which has some 24,000 outposts, while domestic challengers such as Blank Street, Scooter’s, and Dutch Bros have found footholds in being anything but another Starbucks.

Starbucks’s transactions peaked around 2019, according to Niccol, just before the pandemic, and its revenue is stagnating. Starbucks managed to bring in $36 billion in fiscal year 2024—nearly flat with 2023—by offsetting dwindling customer numbers with higher prices.

Changes in leadership haven’t helped. Niccol’s predecessor, Laxman Narasimhan, lasted just 17 months as CEO, despite his endorsement by the company’s legendary leader, Howard Schultz. Narasimhan was pushed out last August amid falling sales and activist campaigns by Elliott Investment Management and Starboard Value.

Niccol’s recruitment was the last major act of now-retired board member Mellody Hobson, who was banking on his reputation as the world’s leading fast-food strategist and a digital tactician. But it’s also a bit of a gamble. For this brand turnaround, the master of operational efficiency needs to focus on something radically different: improving customer experience. “The operational process is what’s going to free us up to give a great experience again,” Niccol tells me.

During his six years at Chipotle, Niccol revived the chain through heretical acts within the lo-fi company: adding a second “make line” to service online orders, giving cooks screens to smooth out logistics, and using digital rewards to entice customers. Before that, at Yum! Brands—Niccol was chief marketing officer of Pizza Hut and then Taco Bell, eventually becoming CEO of the latter—he launched apps for both brands, bolstering their sales. At Chipotle and Yum! Brands, Niccol accelerated the shift to digital orders.

But Starbucks doesn’t need to digitize its operations. Today, 31% of its orders are already placed within its rewards-laden app, which is so effective that it’s become something of a North Star for the fast-food industry.

If anything, digital orders are working too well, undermining the ecosystem of a Starbucks café. Over the past decade, Starbucks has become known for chaotic stores staffed by baristas who struggle to keep pace with orders; unpredictable waits that have made mobile ordering a defensive strategy to get your coffee on time; and cafés that offer neither the space nor seats for customers to hang out or work at their laptops. For many people, the daily ritual of a Starbucks latte no longer feels worth the (considerable) price or trouble.

“When the opportunity at Starbucks popped up, I spent a little bit of time looking at, ‘Okay, what makes Starbucks Starbucks?’” Niccol says. “It was clear that everybody really had a connection to the experience. And unfortunately, a lot of them talked about it in the past tense.”

The Starbucks machine, Niccol argues, had gone too far, replacing hand-scrawled Sharpie names on cups with printed labels, overwhelming baristas so they didn’t have time for human connection, and either ripping out café seats entirely during the COVID-19 pandemic or replacing them with the sort of hard, “15-minute chairs” that, legend has it, Ray Kroc pioneered at McDonald’s. In Starbucks’s early years, Schultz borrowed from urban theorists to describe his cafés as the “third place” between work and home. Niccol aims to not just revive that idea—but to reconcile it with the iPhone era.

Nearly a year into the job, his plans are still solidifying. He brought back the Sharpie and updated the dress codes for baristas (despite protests). He’s offering free coffee refills, and he’s reintroduced the condiment bar so that customers can add cream to their coffee themselves and stopped upcharging for alt milks. (He also no longer offers free water to non-paying visitors, to discourage loitering.)

Bigger changes are coming, including the redesign of 1,000 of Starbucks’s 11,000 company-operated cafés in North America by the end of next year, and adding 30,000 seats back to stores over the next few years. Niccol is also planning to sunset the company’s 90 or so mobile-order and pickup-only stores, which he has described as “overly transactional.”

“We were creating soulless vessels to just hand people coffee. That isn’t right,” says Niccol. “I’m going to win more drive-through and mobile orders because of the coffee experience that you have every once in a while when you sit in our café.”

In the restaurant industry, store redesigns are part of a proven playbook, says Bank of America senior research analyst Sara Senatore. “People want to go where [other] people are,” she explains. “That free refill isn’t just for people who get the refills, just like the seating isn’t just for people who use the seating. That visual is important for everybody.”

Whether Niccol’s changes are coming quickly enough for Wall Street is another matter. For the third quarter of fiscal year 2025, Starbucks grew revenue by just 4%, while same-store sales declined by 2% in the U.S. and 2% globally—marking six quarters in a row of same-store sales declines.

There are early signs of success: An increasing number of stores are seeing growth in transaction volumes; non-rewards customers are starting to return. But even Senatore, a Starbucks bull, noted on the company’s April earnings call that “it’s a little slower in terms of earnings recovery than maybe some of the previous turnarounds we’ve seen from you, Brian.” Chipotle’s same-store sales had improved the quarter Niccol arrived.

But with Starbucks, the challenge is more complex: No one ever cherished Chipotle for its plush seats and warm atmosphere.

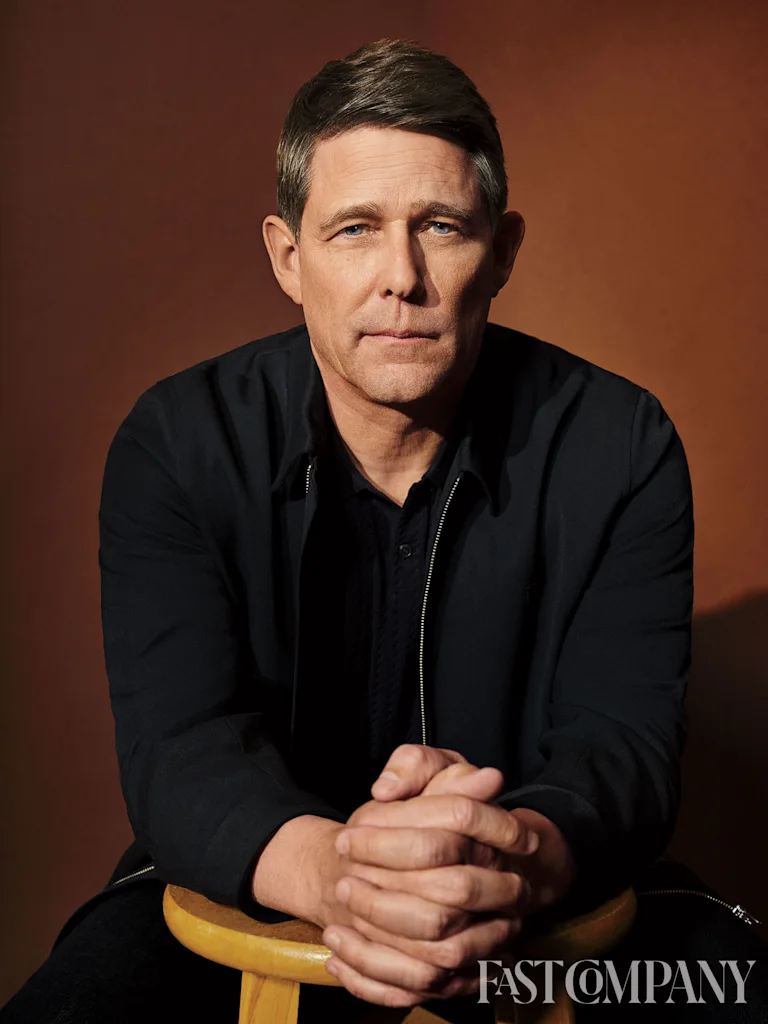

Mike Grams, COO of Starbucks, walks into a Starbucks bathroom and inhales, filling his nostrils like he’s breathing the Alpine air of a Ricola commercial. The bathroom, thank god, smells like air freshener.

We’re at one of Starbucks’s first redesigned stores in Bridgehampton, New York, and, alongside Meredith Sandland, Starbucks’s EVP and chief coffeehouse developer, Grams is taking me on a “coffeehouse walk,” where he surveys the customer experience of a Starbucks.

The duo, who are both just 100 days into their new roles, last worked with Niccol at Taco Bell. Niccol coaxed Grams, who had risen from store manager to COO at Taco Bell, out of retirement to help resuscitate Starbucks. (Niccol describes Grams, who brims with football coach energy, as a “human quad shot.”) Meanwhile, Sandland, the former chief development officer at Taco Bell, spent the past three years building ghost kitchens software at the startup Empower Delivery. When she joined Starbucks, the coffee chain licensed Empower’s software and hired six of its engineers.

Grams’s coffeehouse walk will soon be practiced by Starbucks’s 1,000 North American district managers, who visit different cafés a few days a week. On this afternoon, he begins outside the store, inspecting the Starbucks sign for bird nests. Then he walks through the space with all his senses on alert, ensuring sounds, sights, and smells layer harmoniously.

Sandland notices the store’s music is a bit too loud for conversation, but she’s pleased to hear the coffee steam behind the counter. Grams catches a thin line of dirt piling up at the threshold of the exit door. “It’s easy to walk past very basic things,” Grams says.

Getting the store design right is another challenge. Today, most Starbucks locations are a study in stark white, black, and gray; every surface has been hardened for easy cleaning, down to the chairs. The result is a space that’s fine to look at but miserable to linger in, built less to be sat in than hosed off.

“[Our] coffeehouse needs to be better than any living room you’re in,” Niccol says, citing “affordable luxury” as the company’s new guiding principle. It’s easy to see why the company chose to show off this café to me. It’s cozy, with rich green walls and louvered shutters on the windows. The worn wood floor has been refinished instead of covered over with Starbucks’s usual tile. Books sit on shelves. Large plants fill corners.

The counter, with its drab display of sample food items, will also get an update. Grams points to the pastry case, where flat frozen croissants are presented as if for autopsy on sterile white plates. Those plates will be replaced with baskets and fluffier croissants, freshly baked in-house.

is helping Starbucks streamline operations with new software. [Photo: Jessica Chou]

Under Niccol, the company is also reviving multi-zone seating, pockets that are meant to serve different purposes. Here that includes a large wooden dining room table where remote workers can use their laptops, as well as low, plush chairs for reading. Café tables, still set with those hard 15-minute seats, allow pairs of people to catch up. But in other areas, those chairs are topped with a one-inch leather cushion, making them more inviting.

The biggest update may be the new padded leather bench seating. When I settle into it with my full weight, I find it’s both comfortable and supportive of my back. It’s also great for adding seating capacity to smaller stores.

Niccol has commissioned some additional furnishings. They include glasses and mugs that will nod at the siren while remaining “elegant,” he says, and what he calls an “iconic” chair—something so comfortable and expensive it might only appear in half or two-thirds of stores, a throwback to the quirky purple Starbucks chair of the ’90s. “It’s got to be the seat that when you walk in, you’re like, ‘Man, I can’t wait for him to get up. I’m hopping in that chair the second he does,’ ” Niccol says.

Analysts had estimated that these redesigns—which are now debuting across New York and Los Angeles, and spreading to 1,000 stores over the next year—could cost as much as $1 million apiece. Niccol insists that’s an overestimation of what he calls a store “uplift.” He characterizes what he’s rolling out now as “cosmetic renovations,” and says they’ll cost around $150,000 apiece and can be accomplished over the course of a single night. (He also puts the price tag for a true store renovation at about $450,000 or less.)

The effect can be contagious: Historically, even having just one fancier Starbucks café in an area has driven repeat business to half a dozen lower-touch stores in the vicinity. And improving a store experience has a rapid effect on a brand’s reputation. That’s why, back in 1999, Starbucks hired Ted Jacobs as an early global head of design. He’d helped reinvent retail with the launch of flagship NikeTown stores in cities around the world.

But even the most enticingly redesigned stores will feel superficial if Starbucks doesn’t find a solution for its biggest problem: the pool of customers hanging by the counter for their drink order, ruining any feeling of coziness. It’s an issue that has plagued the company for a decade.

Bill Sleeth, who was the VP of design at Starbucks under Schultz from 2010 to 2017, remembers exactly when things went awry. After the company’s rapid expansion in the early 2000s, when it adopted a somewhat cookie-cutter approach to store design, Sleeth worked to infuse the cafés with more comfortable and local elements. He also introduced the high-touch Reserve stores to bring a halo effect back to the brand.

With Sleeth’s initial global store redesign strategy working (the company’s same-store sales grew between 6% and 9% annually between 2010 and 2015), he began testing novel store layouts to help reduce the line of customers waiting to place orders.

But the company’s tech team had other plans. In September 2015, Starbucks launched Mobile Order and Pay nationwide. “The whole thing took us by surprise,” Sleeth recalls. “If it had been just a few orders—just a convenience for customers—it wouldn’t have been a big deal. But it completely transformed the business.”

Previously, every Starbucks had been designed to accommodate a winding queue in front, right before the cash register. But mobile-order pickups essentially repositioned the crowd to an ad hoc holding pen after the register. Cafés simply didn’t have the space for this. So drinks piled up on counters, and customers pooled into the middle of the store.

Sleeth’s team built little risers to hold all the drinks ready for pickup, and more recently, Starbucks updated stores to move the drink area closer to the front doors. Even so, the vibe for anyone sticking around is grim.

“Our stores blew up in our face. Our success became that handicap,” Sleeth says. “It broke us.”

Michelle Eisen was a Starbucks barista in Buffalo when, in 2015, she and her colleagues began affixing receipt-like stickers onto all cups instead of hand-writing names. They loathed the automation. “We were resistant,” she says. “It seemed contradictory to the experience we were supposed to provide.” In her eyes, the paradigmatic Starbucks coffeehouse disappeared along with those Sharpie-signed cups.

But nearly 10 years later, Niccol’s mandated use of the Sharpie was, to Eisen, even worse. Head counts had been quietly cut over the years—the average Starbucks store had 24 employees five years ago; today, it has 18—even as the drink menu became increasingly complicated. The job had gotten harder.

One of Niccol’s first orders of business was paring back that menu, eliminating 30% of options, things like melon syrup and freeze-dried pineapple. (Though he is introducing a protein cold foam.) But Eisen says that customers still came in and asked for their old standbys, and she found it impossible to turn them down. And then, suddenly, she was supposed to pick up a Sharpie and start writing on dozens of cups per hour.

“I’m an experienced barista, and [even] I struggled, especially during peak. If I could get a smiley on every cup, it was a huge feat,” she recalls. “It’s awful to feel like you’re doing everything in your power and you’re just drowning.”

In May, Eisen quit her job to join the Starbucks Workers United union as a full-time organizer, helping baristas around the country join the ranks of the 12,000 employees across 620 North American stores who have voted to unionize as of time of publishing. (In addition to its 11,000 company-operated stores in the region, Starbucks has 7,000 licensed ones; the company runs just over 50% of its stores globally.)

Eisen offers a counter perspective on Niccol’s Back to Starbucks plan, outlining how something as simple as updating the dress code—from tops of any color with faint patterns to clean black T-shirts—had massive repercussions for employees without washing machines, who can be sent home without pay if they fail to comply (many baristas spill on themselves at least once a shift).

She also points out that refusing a visitor’s request for a cup of water “always ends in a fight,” making a case that Niccol’s operational updates have largely come at the expense of the already beleaguered workforce.

Indeed, after Niccol announced the dress code updates in April, the union responded with coordinated strikes across 175 stores, creating a terrible public relations moment for a company attempting a turnaround. (According to analyst firm Paragon Intel, Niccol’s lack of experience negotiating with unions is one of his few weak spots as a CEO: The National Labor Relations Board found Chipotle violated labor laws under his leadership by closing a store in Maine that was attempting to unionize.) Starbucks and the union are currently in stalled contract negotiations, with pay increases a sticking point.

Niccol seems to acknowledge his early missteps. In our conversations, he floats the idea of charging a quarter for Starbucks’s triple-filtered water. He also wonders if he should have first tested the dress code at the company’s new “Starting Five” stores—five cafés where Starbucks corporate now tries out products and ideas before releasing them more widely. But overall, he defends the moves.

“Ninety percent of the people’s feedback was hugely positive. The 10% that decided to be very public about their dissatisfaction got a lot of pickup, and I was surprised by that,” Niccol says. “But I think we made the right choice.”

He sees Starbucks’s labor challenges as rooted in operational problems. Back-of-house updates, he argues, will buy back time and sanity for the staff and create a warmer atmosphere for customers—ensuring baristas have the wherewithal to provide the hospitality of remembering customers’ names and handing them their drinks.

The company’s biggest target is Sleeth’s former nemesis: mobile ordering, which produces a sea of tickets that can overwhelm staff. (Niccol likens this dynamic to a memorable scene from The Bear, when the kitchen at the Chicago sandwich shop is so flooded by online orders that the staff just gives up.) This September, Starbucks is rolling out new logic for Mobile Order and Pay called Smart Queue. Instead of cueing baristas to make drinks (ordered in the store and online) on a first come, first served basis, it will more intelligently prioritize orders.

In-store drinks will be ready within four minutes and online orders within 12 minutes, while food and drinks will be grouped together. People ordering via the app will be able to select a pickup time for 15 minutes or further into the future, the sort of simple upgrade that will allow practical prioritization. Niccol reports that 80% of in-café orders are handed off within four minutes in stores that are already using Smart Queue.

Sandland, as head of store development, is leading the project. “There might be the same number of people coming in to get their drink, but if you can better match the right drink to the right person, there’s going to be fewer drinks sitting on the bar and fewer people” hanging around waiting, she says.

Other updates include a point-of-sale terminal that lists 82% of orders as one-tap buttons on the home screen for cashiers, making it easier for them to keep things humming along. There’s even a tab for viral fan-made drinks, which Starbucks promotes through a new Secret Menu in its app. (The company scours social media for these drink ideas, tweaking recipes for scalability.)

Starbucks is developing an espresso machine that pulls four shots at a time instead of three, saving 27 seconds when someone orders a quad shot, which it hopes to start rolling out next year. And it’s upgrading software to make it easier for managers and employees to swap shifts.

Then there’s the question of staffing. When I was in Las Vegas, I found myself in an elevator with two store managers. I mentioned that I was going to meet Niccol and asked if they had one design request for him. After a few moments of contemplation, one of them simply said, “More staff.”

Niccol gets it. “The fundamental fact is we’re going to have more people in the stores servicing customers. There’s no other solution. It’s a human-to-human business. We’re going to put in the additional one, two, three people. Let’s just say the roster of 18 becomes 20.” These hirings should take place over the next year and will cost the company roughly $500 million. To pay for them, Bank of America analyst Senatore estimates that prices will need to go up by 3% or sales will need to grow as much as 5%. Starbucks plans to offset these investments with cost savings across the company.

Starbucks has also announced that it will add an assistant manager role to every store, someone promoted from within, to take pressure off managers who often spend their days off handling tasks like scheduling. When this policy was announced on stage in Vegas, the crowd of managers roared.

Niccol is so confident in his vision that he’s already thinking ahead to when Starbucks could more than double its global footprint, reaching 100,000 stores. He details a plan based on three store sizes—which he laughingly calls “tall, grande, and venti.” (He’s especially bullish on the “tall” store, a cozy, cost-effective espresso bar format with approximately 10 seats; the first will open in New York City.) Most will have drive-throughs. All will have seats.

Niccol also denies that Starbucks is planning to sell off its China business, saying he’s keeping the stores and would like to expand to 20,000 in the country with the “right partner.”

This expansion seems a touch quixotic when Niccol concedes that only a “handful” of new stores can open in North America in 2026 with “dozens” following in 2027, given the lead time involved with obtaining permits. And he still needs to validate his model.

He’s been pulling new levers to create urgency inside the company. In July, he offered his three top executives $6 million in stock grants if they hit cost-savings targets by the end of the year—and double that if they implement his in-store policies more quickly. He also mandated that corporate employees return to office, in Seattle or Toronto, for at least four days a week by October. (Following criticism of his initial plan to work remotely from Newport Beach, Niccol now works out of the Seattle office.)

Still, there’s one major question looming over Niccol’s Back to Starbucks plan. Even if Wall Street gives him the time to revive the “third place,” do customers still want it?

Starbucks is just one of many quick-service restaurants that have ripped out seats and opened smaller stores over the past several years. The third place didn’t just die at Starbucks; it’s disappeared across much of our world. In the era of DoorDash and, yes, mobile ordering, customers increasingly view fast-food restaurants as vehicles for food, not ambience.

To Niccol, that presents an opportunity. “That’s where the value of Starbucks comes to light, because it’s so much more than just a cup of coffee,” he says. “There aren’t many places like this anymore.”

Bringing hospitality back to the hospitality industry shouldn’t be a novel idea. In 2025, that’s all the more reason it’s essential.