- | 9:00 am

Silicon Valley wants its own Steven Spielberg, and it thinks it’s found him

The tech world hates Hollywood’s downbeat, “Black Mirror”-style portrayals of the tech future. Jason Carman, a 25-year-old filmmaker, is determined to change that, starting right now.

It was an ambitious goal, but Hollywood was built on ambitious goals.

Jason Carman gave himself until his 20th birthday to make a high-concept, effects-driven short film that would capture the attention of studio executives, convincing them to toss him the keys to a megabudget feature.

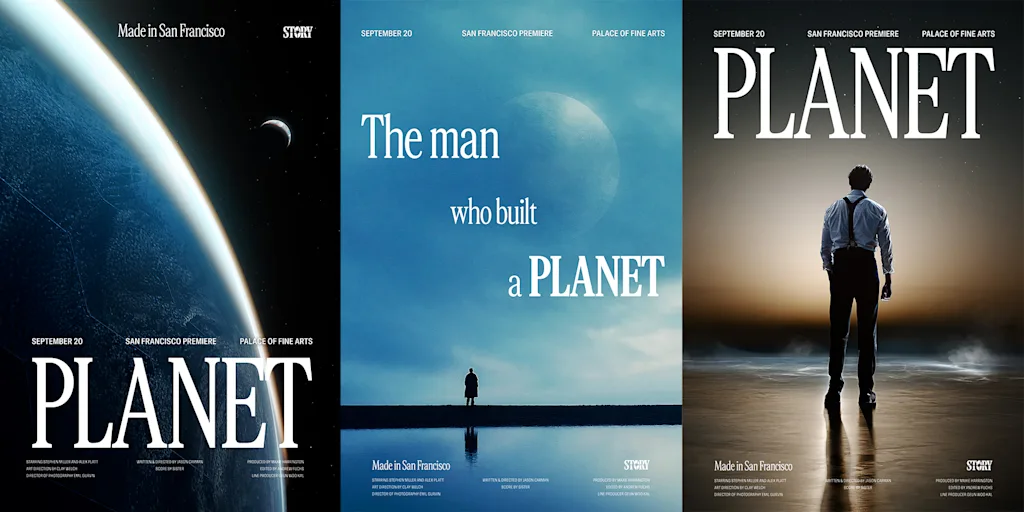

Now, at age 25, having missed his deadline by a smidge, Carman is on the verge of enjoying a splashy debut for his sci-fi short, Planet, at San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts on Saturday. The question is whether studio executives will take notice—and, if they do, whether Carman can parlay that attention into his bigger ambition: injecting a sense of techno-optimism into Hollywood movies.

Stranger things have happened, both on-screen and off.

Following a two-year stint as head of content at aerospace hub Astranis, Carman launched the creative studio Story Company in 2024. If any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic, as Arthur C. Clarke famously put it, Carman was blown away by his time backstage at the magic show, and wanted to sell more tickets. With Story, the young filmmaker could extend his tech-evangelism to branded work for new clients like medicinal robot-maker Multiply Labs, while also making documentaries and sci-fi projects of his own.

“My goal with our movies is to give people a taste of what I experienced working at a company like Astranis,” he tells Fast Company, “where I got to feel what it’s like building cutting-edge hardware and science every day.”

In his former role, Carman had spent a metric ton of time with aerospace engineers. They were the most interesting people he’d ever met: die-hard sci-fi heads who named meeting rooms after Star Wars characters and would not shut up about the latest Andy Weir novel—all while building spacecraft that pantheon-straddling sci-fi writers like Isaac Asimov could only dream of.

Those tech workers’ enthusiasm for building a bridge to the future proved infectious, and it was something Carman sensed was sorely missing from multiplexes. He wanted to be the one to provide it. All he had to do was convince everyone else he’s up to the task.

The future, according to Hollywood

Carman grew up a couple hours north of Silicon Valley, in Vacaville. He was a child obsessed with movies, especially blockbuster multi-film franchises like Star Wars. From the age of 9, he was convinced he was destined to launch a company that creates them.

He did not wait until he was old enough to know what an LLC was before getting started.

At age 14, Carman won a Best VFX Award at the All-American High School Film Festival for his sci-fi short Vacuum Wars, which is not what it sounds like. The early effort—a precocious pursuit not unlike Steven Spielberg’s own early sci-fi feature Firelight—features grunts facing off against nimble, neon-flecked robots in all manner of combat. It does not look like it was executed by a high school freshman, even if the dialogue admittedly sounds like it was conceived by one. Carman’s short film was impressive enough, though, that the University of Advancing Technology in Arizona offered him a full scholarship, which he declined.

“I had YouTube tutorials and access to open source forums,” he says, citing technology unavailable to every preceding generation of aspiring filmmakers.

After high school, Carman quickly found work at 2K Games, the company behind the NBA2K and Borderlands video game series. While directing trailers for new titles and assembling social media content, his quest to make the short film that announced his talent to Hollywood slowly migrated to the backburner. It wasn’t until he later took the job at Astranis that his passion for sci-fi filmmaking reinvigorated, sparked by his new proximity to ground zero for science fact.

“These exceptional people in this industry were all deeply influenced by science fiction,” he says, “and I think it’s because they felt like it was a blueprint for what they wanted to build.”

At a certain point, he grew weary of the popular cinematic suggestion that all their efforts would ultimately be in vain, or worse. Carman cites Netflix’s anthology series Black Mirror—in which someone’s device is always leading them to their demise—as a particularly egregious example of tech-based “fear-porn.”

But humanity has been routinely hurtling toward doom in sci-fi films, often courtesy of Big Tech, for decades—from Terminator to The Matrix, and from Ex Machina to M3GAN. The entire Alien franchise depicts corporations using tomorrow’s state-of-the-art technology in despicable ways—with the latest entry, the Hulu series Alien: Earth, reaching the only logical conclusion, its titular monsters finally attack our home planet.

When movies aren’t depicting the fall of mankind, they’ve lately portrayed the heads of tech companies as bumbling creeps, in projects like Glass Onion and Mountainhead. Adam McKay’s Don’t Look Up even managed to feature both a wackadoo tech CEO and the apocalypse.

Carman has a theory about why so many sci-fi filmmakers seem pessimistic about the future.

“We as humans naturally have a negativity bias,” he says. “It’s what’s allowed us to survive for tens of thousands of years. And I always say it’s easier to scare people with a negative story than it is to inspire people with an optimistic one.”

Perhaps darker sci-fi films in the lineage of 2001: A Space Odyssey are meant as stark, necessary warnings about the dangers of playing with Promethean fire. Or maybe the reason this pattern runs so deep is because hubris makes for a compelling narrative target, and some corners of the tech sector are objectively rife with it. Either way, there appears to be a rising sense in Silicon Valley that Hollywood needs to lighten up and let technology simply be awesome.

“I love sci-fi movies but I think we’ve hit a spot where a lot of them have just gotten too dystopia-based,” says Jim O’Shaughnessy, the CEO of O’Shaughnessy Ventures, which recently backed Carman’s company. “There’s a place for those movies, for sure, but it would be nice to see a more optimistic view of what the future can be, and I love that Jason [Carman] has one.”

A filmmaker is born

There’s a long history of science-fiction concepts paving the way for technological breakthroughs. The Personal Accessory Display Devices from Star Trek, for instance, predicted the form-factor of the iPad and other tablets. The guy who envisioned the look of the memorable gesture-based tech from Minority Report ended up inventing a version of it in real life much later. The Metaverse from Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel Snow Crash influenced, well, you know.

With a front-row seat to the forefront of aeronautics, Carman vibrated with excitement over the possibilities his new cohort might bring to life—and the idea that he might one day conceive of a sci-fi idea that could influence the next wave of tech workers.

He became so inspired while making videos to promote the aerospace company’s innovations, he started spending his Saturdays with different tech startups, and making short documentaries about everything from joyriding jetpacks to literal rainmakers. He made dozens of these films, working so many nights and weekends he got sick seven times in a year.

It was exactly this level of bone-deep dedication and enthusiasm, along with the progression of Carman’s craft, that convinced O’Shaughnessy to back Story Company last year.

“We read his fellowship application and watched the videos he had made and we said, ‘This seems like a guy who really could become a younger version of Spielberg.’”

Part of the reason for Silicon Valley’s burgeoning sense of betrayal over how tech is portrayed in movies may be due to the fact that filmmakers have a lot in common with founders. They command large staffs, work wild hours, and sometimes have billions of dollars on the line. David Senra, host of the popular Founders podcast, seems to admire the actual Steven Spielberg more for his galactically lucrative deal securing a cut of Universal Studios theme park ticket sales than for making some of the most enduring works of art in modern history.

Increasingly, those who are sick of watching AI portrayed on-screen as humanity’s death drive made manifest are now branching out into making films of their own. It’s a proud tradition going back at least to when David Sacks used his PayPal windfall to produce the 2005 film Thank You for Smoking, with the help of pals Peter Thiel and Elon Musk.

Now, Palantir chief technology officer Shyam Sankar is raising funds to launch the aptly named Founders Films, which would focus less on optimistic sci-fi than Ayn Rand adaptations and other “projects about American exceptionalism,” while Andreessen Horowitz is backing the new studio Promise, which will produce films and series using generative AI tools.

“Every major figure in tech right now is trying to fund movies,” Carman says.

Unlike those other nascent studios, Carman says Story Company will be less focused on creating a sort of Shadow Hollywood than in telling stories that celebrate technology as “the tool that differentiates humans from every other species in the animal kingdom.”

He sees the studio’s branded work for clients like Rangeview, Valar Atomics, and his former employer Astranis serving a similar purpose as the sci-fi trilogy he plans to make: using wow factor to hack viewer’s inspiration receptors. One of Carman’s future projects is adapting the Bell Labs biography, The Idea Factory, into a feature for O’Shaughnessy’s Infinite Films shingle. But first, of course, there’s Planet.

Story’s first sci-fi short adds a dash of Interstellar-style world-building to the logistical dynamism that impressed Carman in the tech world. Even the process of making Planet, which is about an astrobiologist who creates an artificial planet, surprised Carman by being so similar to what he’d previously only documented. It was an iterative feat, in service of making a minimum viable product, which he hopes will prove Story’s functionality in ways a pitch deck cannot.

If the film ultimately does convince some intrepid studio executive to throw Carman a hefty budget, it will be a real Hollywood ending.

Or maybe more of a Silicon Valley ending.