- | 9:00 am

Is the AI productivity paradox really a human problem?

Experts say the technology is advancing faster than organizations can adapt, and that human behavior–not AI itself–is the real bottleneck to measurable productivity gains.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is advancing rapidly, but its ultimate impact remains uncertain. The World Economic Forum (WEF) contends that AI’s effects are defined less by technological inevitability and more by how competing forces—across jobs, productivity, energy, and generational engagement—will shape its role. The forum points out that the future of AI will depend on human choices, organizational strategies, and global politics, not just on new technology or market shifts.

Even as some warn of an “AI bubble” and spending on data centers soars, governments and businesses everywhere are rushing to use AI.

In such a situation, experts say we need to focus less on quick wins and more on building systems that create lasting, shared value, but making this happen at scale is proving tough.

WHY AI’S GAINS ARE HARD TO SEE

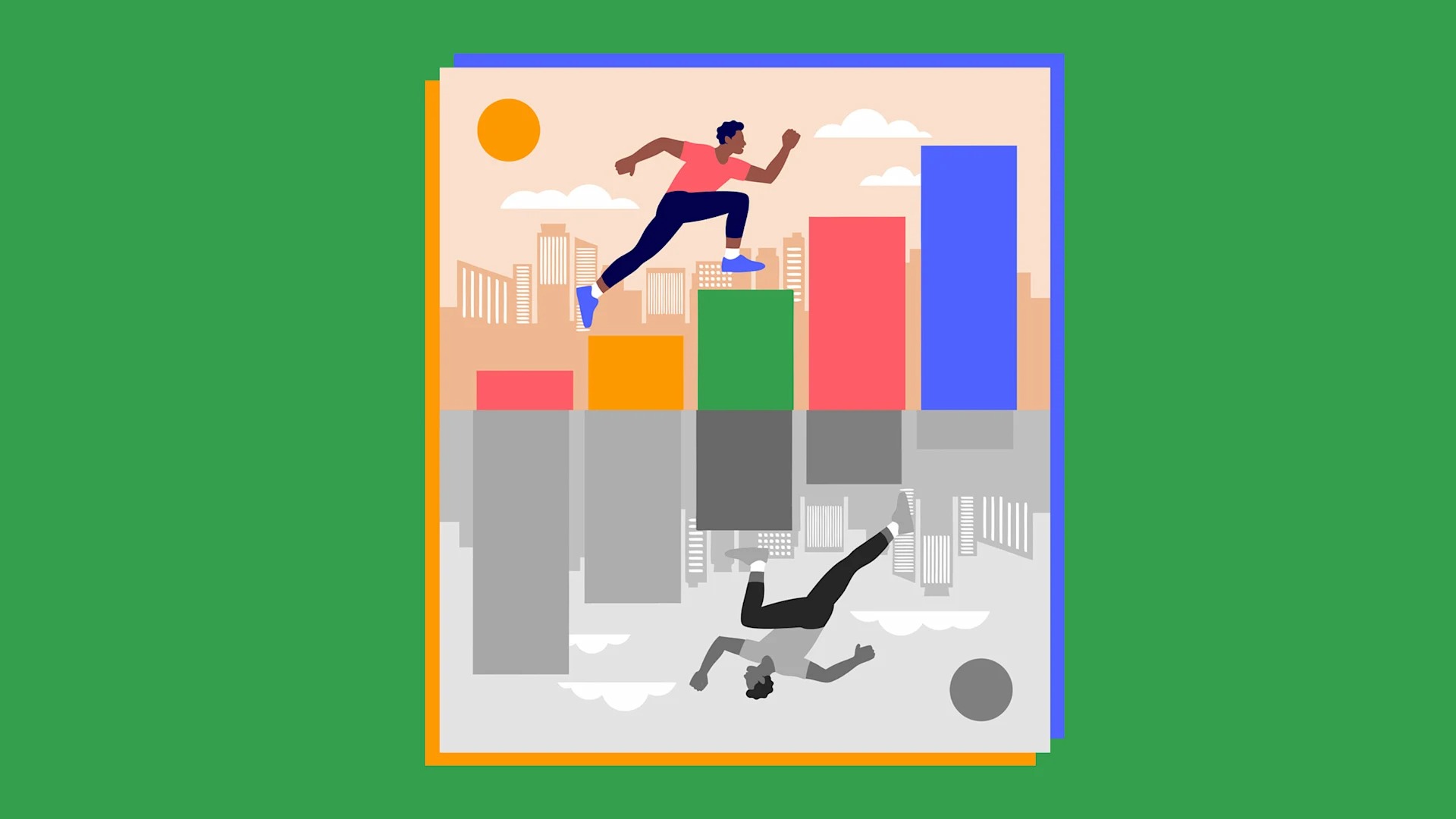

Despite rapid advances in AI, its impact on productivity remains elusive in official data. One reason, executives say, is that AI adoption is uneven, not just across industries, but within companies themselves.

“Some companies use AI every day. Others do not use it at all. The same applies to the departments inside the company,” says Cosmin Ivan, CEO of Platinumlist. “Strong gains from a few teams are hidden by many teams with no change. So the average looks flat, even if AI works very well in some places.”

Standard ways of measuring productivity, like output per hour or revenue per employee, don’t capture these differences well. Gadzhibala Pirmagomedov, Project Owner at Syrve, says that AI often leads to improvements that aren’t reflected in these numbers. “AI often improves things that don’t show up in these numbers, like better decision-making, fewer errors, or reduced waste,” he says, using the restaurant industry as an example, where smoother operations are just as important as how much is produced.

From a systems perspective, Andrew Baturin, CMO at Tumodo, adds that most organizations are still relying on legacy KPIs. “In practice, AI-driven gains are often hard to capture because many benefits relate to time savings, process acceleration, or quality improvements that were not embedded in legacy metrics,” he says, noting that these benefits also tend to appear with a delay.

Another reason productivity data is unclear is that AI adoption is happening at different speeds. Big companies are moving faster, while smaller ones are falling behind, which makes overall gains look smaller. “It’s massively uneven right now,” says Pirmagomedov.

“Some restaurants (like larger chains) are using AI for everything from demand forecasting to customer personalisation, while others are still using spreadsheets. When you average it all together, the gains from early adopters are lost in the noise.”

Baturin agrees, saying that we won’t see clear productivity gains in the data until enough companies use AI in similar ways. He estimates that until about 30-40 percent of businesses adopt AI in a standard way, its impact on the whole economy will stay limited.

LEARNING CURVES AND THE COST OF CHANGE

Even when companies start using AI, productivity doesn’t go up right away. In fact, it often drops at first.

“AI tools are fast, but people are not,” says Ivan. “Teams need time to learn how to use them well. At first, work can even slow down. People test, make mistakes, and rebuild processes. During this phase, costs go up before results show. Stats usually catch the cost first, not the benefit.”

A lack of the right skills makes this delay worse. “AI tools need new skills. Many workers do not have them yet,” Ivan adds. “Productivity drops first and improves later. This delay creates the paradox.”

Trust is another challenge in day-to-day work. Pirmagomedov points out that managers often hesitate to follow AI advice at first. “It takes a few weeks or months before teams really adapt and see the full benefits,” he says.

A BOOST FOR THE HIGHLY SKILLED, AT FIRST

At first, AI’s productivity gains mostly benefit highly skilled workers, making the results even more uneven.

“Yes, AI mostly helps high-skilled workers first,” Ivan says. “These people already do complex tasks like analysis, writing, and decision-making. Their productivity increases fast. But many other roles change slowly.”

Pirmagomedov agrees, though he points out that AI can also support less experienced staff. The issue, he says, is distribution. “Some people get way more value out of it than others, which makes the impact harder to measure.”

Baturin says these benefits often stay within certain teams. Unless more of the organization adopts AI, these gains won’t show up as a significant increase in productivity.

MORE VALUE, LESS VISIBILITY

As AI handles more routine work, people are moving toward tasks that are harder to measure, like creativity, coordination, and judgment.

“AI reduces routine work and pushes people toward thinking, planning, and creative tasks,” says Ivan. “These activities create value, but they are hard to measure with classic productivity metrics.”

In the food and beverage sector, Pirmagomedov sees the same pattern. “A manager doing less admin work and more relationship building is more productive, even if there is no way to put it on a spreadsheet,” he says.

Baturin points out that in marketing and communications, AI speeds up content creation and strategic work. These results improve decision-making but are hard to measure with simple metrics.

A TEMPORARY PARADOX?

Even though the situation is unclear, experts think the AI productivity paradox is mostly temporary.

“New technologies usually show weak results at first. Real gains appear only after companies change workflows, roles, and habits,” says Ivan.

Pirmagomedov frames it as a familiar cycle. “Every major technology goes through these phases of initial investment, early adoption, and learning period, then the maturation and levelling off,” he says.

From a historical standpoint, Baturin agrees. While AI adoption is faster than past technological shifts, he argues that measurable productivity gains will still depend on time, scale, and standardisation. Until then, AI’s real impact may remain visible everywhere–except in the data.

SO IS THE PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX A MYTH?

Not everyone thinks AI’s productivity puzzle is really a paradox. Andreas Hassellöf, CEO of Ombori, believes the issue isn’t the technology itself but how organizations decide to use it.

“The so-called AI productivity paradox is not a paradox at all. The technology works. What fails is how organizations adopt it,” Hassellöf says. “Many companies buy AI licenses, announce they are investing in the future, then wonder why nothing changes. That is like buying gym equipment and expecting to get fit without changing behavior.”

From his vantage point across enterprise deployments, Hassellöf sees a recurring pattern: Early experimentation, shallow use, and premature disappointment. “People tried AI tools early, got mediocre results because they did not know how to use them well, and dismissed the entire wave as overhyped,” he says. “Meanwhile, technology has evolved faster in the past two months than in the year and a half before that. Mental models are completely out of sync with reality.”

Where many analysts focus on skills gaps or learning curves, Hassellöf places the emphasis squarely on human resistance. “The real blockers are human. Fear, ego, and bureaucracy play a much bigger role than the tools themselves,” he says, pointing to professional identity as a critical friction point. “Developers, for example, often resist AI even though it directly affects their work. When tools shift their role from writing code to specifying and reviewing, it challenges how they define their value.”

This discomfort, he argues, mirrors earlier technological transitions. “This shift mirrors what happened in photography. Digital cameras did not reduce the value of a photographer’s eye or storytelling ability. They amplified it,” Hassellöf adds. “AI is creating the same transition away from execution and toward judgment, taste, and meaning.”

Ironically, enterprise controls designed to reduce risk may be slowing transformation even further. “Security and governance reduce AI to copy-and-paste workflows,” he warns. “That is expensive autocomplete, not transformation.”

For Hassellöf, the stakes are no longer theoretical. “When AI enables one person to do the work of ten, leadership choices determine whether that leverage delivers 10x economic growth or results in massive layoffs,” he says. “The technology has already moved forward. Humanity needs to catch up.”

When you combine new data and leaders’ experiences, his view changes the discussion. What seems like a productivity paradox might actually be a gap between what technology can do and how willing organizations are to change.