- | 4:06 pm

This startup makes carbon-neutral, high-protein pasta from fungi

The key is using a waste product that manufacturers would normally discard: sugar-filled water from food and beverage producers, like breweries.

Early in the pandemic, when her mother was diagnosed with prediabetes, chemical engineer Michelle Ruiz wondered how she could help make the life change easier, as her parents struggled to figure out how to adjust their diets. “We’re from Ecuador, and we found that all the foods that are most culturally embedded in our daily lives are packed with refined carbohydrates that would make my mom’s diabetes worse,” she says.

Cofounders Michelle Ruiz and Andrea Schoen [Photo: courtesy Hyfé Foods]

At the time, Ruiz was working at ExxonMobil and had been considering leaving. “I was really trying to figure out how I was going to leave a bigger legacy in the world than helping a big oil and gas company become more profitable,” she says. As she started thinking more about food, she noticed that a growing number of startups were beginning to use mycelium, the root-like part of mushrooms, to make plant-based meat alternatives for foods like chicken breast. She realized that mycelium also could be used to make a high-protein, low-carb flour for pasta, tortillas, and other foods typically made with wheat flour—options that would be far healthier, especially for someone with diabetes.

[Photo: courtesy Hyfé Foods]

Last year, she began working on a startup, Hyfé Foods, to commercialize the idea. Today, the company came out of stealth and announced a pre-seed round of $2 million in funding led by The Engine, a venture firm spun out of MIT.From her work at Exxon—which happened to involve running a wastewater-treatment plant—Ruiz realized that it could be possible to make mycelium-based products affordable enough to compete with wheat. The key is using something that would normally be discarded: sugar-filled water waste from food and beverage manufacturers like breweries. Breweries pay a surcharge to wastewater-treatment plants to treat that sugary water, a byproduct of brewing, and the process involves using fungi and bacteria to consume organic material in the water. Mycelium, Ruiz knew, could do the same job; growing the material requires sugar as a feedstock.

[Photo: courtesy Hyfé Foods]

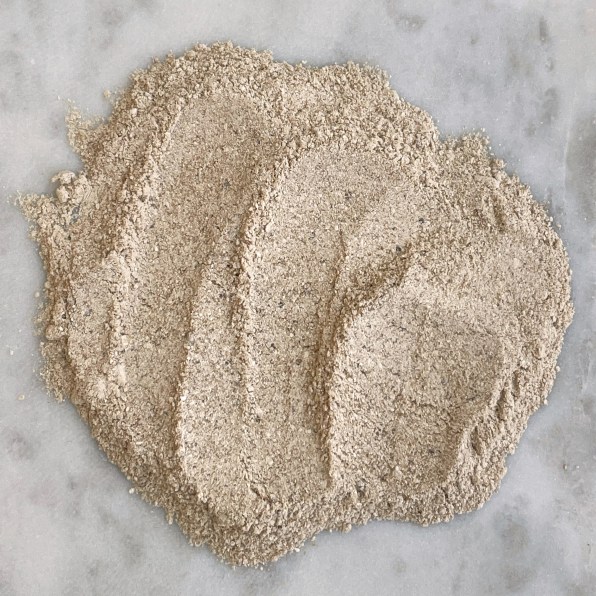

“We were saying, wait a minute, you’re calling that sugar water ‘wastewater,’” she says. “But we in the fermentation space are calling it feedstock. Why don’t we take your sugar water that you’re paying a ton of money to throw away?” For a brewery, paying for wastewater treatment can account for 20% of their operating costs; annual costs can be in the millions. Hyfé Foods plans to charge its partners for processing the water, but will save them money. At the same time, for companies producing mycelium, around half of the cost of production comes from buying sugar, and Hyfé can avoid that cost.The startup will partner with food and beverage manufacturers and build its own production inside their facilities, since moving the water would be too expensive. “We take the water that would normally go down the drain at a very specific point in the plant where it’s still food safe,” Ruiz says. The water goes through a pretreatment process and then gets added to bioreactors filled with mycelium, along with oxygen and micronutrients to help the mycelium grow. The mycelium grows into tiny spheres resembling couscous. Then it’s filtered out of the water, dried, and turned into a flour that can be used to make other foods. Hyfé plans to sell both the flour and finished products to food companies.

[Photo: courtesy Hyfé Foods]

Because the process helps avoid creating waste, it’s actually carbon neutral. At wastewater-treatment plants, after fungi and bacteria chew through the water, they’re filtered out and sent to landfills, where they emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas. At the small wastewater-treatment plant she ran for an Exxon facility, Ruiz says the process created 50,000 pounds of biomass and generated around 4,000 tons of methane a day; the amount created at a brewery is much larger. Because a bowl of pasta made from mycelium has as much protein as a chicken breast, without the carbon footprint, the startup thinks that it can be an alternative for climate-conscious consumers.

[Photo: courtesy Hyfé Foods]

Ruiz and cofounder Andrea Schoen, who previously worked at LanzaTech, a company that turns greenhouse gas emissions into fuel and materials like fabric, first started growing mycelium in Schoen’s basement. Now, with a new grant from Argonne National Lab, they’ll have access to larger facilities, where they’re refining the flavor of their product (when the mycelium-based products are heated, Ruiz says, they have a slight umami, or savory, flavor). By the end of the year, they hope to start building a pilot plant to test the process with a partner.Production could begin quickly enough to begin to respond, to a small degree, to the global wheat shortage caused by the war in Ukraine; right now, countries are relying on some reserves of wheat but are quickly running out. The startup eventually wants to have production facilities inside food manufacturing plants around the world.

“That is the most efficient from a cost standpoint,” Ruiz says. “But then the second part is you’re giving individual regions around the world the sovereignty of producing their own food. It’s a decentralization of food production versus relying on one particular region to produce a specific type of food and then ship it all over the world . . . bypassing the supply chain constraints that we have right now, and just growing and delivering straight to the source.”