- | 4:53 pm

How 100 years of Antarctic agriculture is helping scientists grow food in space

Antarctica is a hostile and extreme climate—which has been a convenient analog for space exploration.

Figuring out how to feed people in space is a major part of a larger effort to demonstrate the viability of long-term human habitation of extraterrestrial environments. On May 12, 2022, a team of scientists announced that they had successfully grown plants using lunar soil gathered during the Apollo moon missions. But this is not the first time that scientists have attempted to grow plants in soils that typically do not support life.

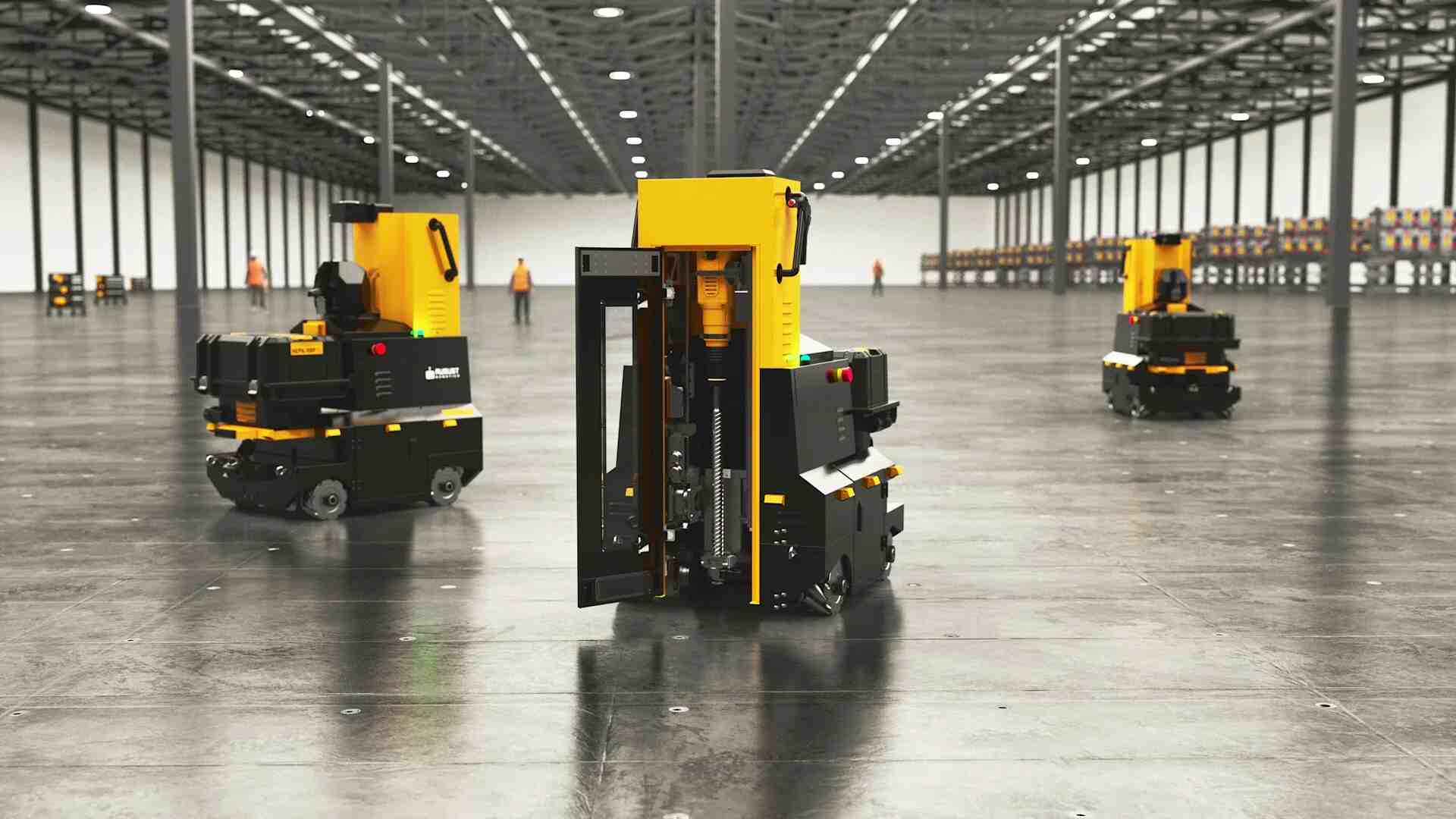

The greenhouse at McMurdo Station in Antarctica is the only source of fresh food during winter. [Photo: Flickr user Eli Duke]

I am a historian of Antarctic science. How to grow plants and food in the far southern reaches of Earth has been an active area of research for more than 120 years. These efforts have helped further understanding of the many challenges of agriculture in extreme environments and eventually led to limited, but successful, plant cultivation in Antarctica. And especially after the 1960s, scientists began to explicitly look at this research as a steppingstone to human habitation in space.

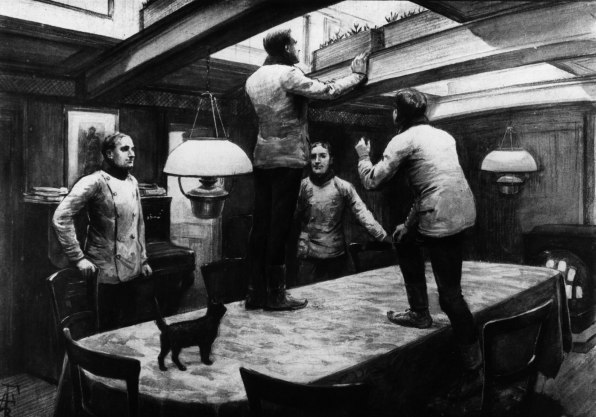

This painting shows a room aboard the Antarctic research ship Discovery, where the first plants were grown using soil from Antarctica. [Image: Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

GROWING PLANTS IN ANTARCTICA

The earliest efforts to grow plants in Antarctica were primarily focused on providing nutrition to explorers.

In 1902, British physician and botanist Reginald Koettlitz was the first person to grow food in Antarctic soils. He collected some soil from McMurdo Sound and used it to grow mustard and cress in boxes under a skylight aboard the expedition’s ship. The crop was immediately beneficial to the expedition. Koettlitz produced enough that during an outbreak of scurvy, the entire crew ate the greens to help stave off their symptoms. This early experiment demonstrated that Antarctic soil could be productive, and also pointed to the nutritional advantages of fresh food during polar expeditions.

Early attempts to grow plants directly in Antarctic landscapes were less successful. In 1904, Scottish botanist Robert Rudmose-Brown mailed seeds from 22 cold-tolerant Arctic plants to the small, frigid Laurie Island to see if they would grow. All of the seeds failed to sprout, which Rudmose-Brown attributed to both the environmental conditions and the absence of a biologist to help usher their growth.

There have been many more attempts to introduce non-native plants to the Antarctic landscape, but generally they didn’t survive for long. While the soil itself could support some plant life, the harsh environment was not friendly to plant cultivation.

The only way to successfully grow food in the cold environment of Antarctica is inside a greenhouse, like this one at McMurdo Station. [Photo: Flickr user Eli Duke]

MODERN TECHNIQUES AND EMOTIONAL BENEFITS

By the 1940s, many nations had begun setting up long-term research stations in Antarctica. Since it was impossible to grow plants outside, some people living at these stations took it upon themselves to build greenhouses to provide both food and emotional well-being. But they soon realized that Antarctic soil was of too poor quality for most crops beyond mustard and cress, and it typically lost its fertility after a year or two. Starting in the 1960s, people began switching to the soil-less method of hydroponics, a system in which you grow plants with their roots immersed in chemically enhanced water under a combination of artificial and natural light.

Hydroponic systems grow plants without the need for soil. [Photo: Flickr user Eli Duke]

By using hydroponic techniques in greenhouses, plant production facilities weren’t using the Antarctic environment to grow crops at all. Instead, people were creating artificial conditions.By 2015, there were at least 43 different facilities on Antarctica where researchers had grown plants at some time or another. While these facilities have been useful for scientific experiments, many Antarctic residents appreciated being able to eat fresh vegetables in the winter and considered these facilities enormous boons for their psychological well-being. As one researcher put it, they are “warm, bright and full of green life – an environment one misses during the Antarctic winter.”

At the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, researchers have been running experiments designed to mimic growing conditions in space since 2004. [Photo: Daniel Leussler/Wiki Commons]

ANTARCTICA AS AN ANALOG FOR SPACE

As permanent human occupation of Antarctica grew through the middle of the 20th century, humanity also began its push into space – and specifically, to the Moon. Starting in the 1960s, scientists working for organizations like NASA began thinking of the hostile, extreme and alien Antarctic as a convenient analog for space exploration, where nations could test space technologies and protocols, including plant production. That interest continued through the end of the 20th century, but it wasn’t until the 2000s that space became a primary goal of some Antarctic agricultural research.

In 2004, the National Science Foundation and the University of Arizona’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center collaborated to build the South Pole Food Growth Chamber. The project was designed to test the idea of controlled-environment agriculture – a means of maximizing plant growth while minimizing resource use. According to its architects, the facility closely mimicked the conditions of a Moon base and provided “an analogue on Earth for some of the issues that will arise when food production is moved to space habitations.” This facility continues to provide the South Pole Station with supplementary food.

Since building the South Pole Food Growth Chamber, the University of Arizona has collaborated with NASA to build a similar Prototype Lunar Greenhouse.

The International Space Station is home to a small vegetable garden that supplies small amounts of food to the crew. [Photo: NASA]

GROWING PLANTS IN SPACE

As people began spending longer times in space toward the end of the 20th century, astronauts began putting to use the lessons from a century of growing plants in Antarctica.

In 2014, NASA astronauts installed the Vegetable Production System aboard the International Space Station to study plant growth in microgravity. The next year, they harvested a small crop of lettuce, some of which they then ate with balsamic vinegar. Just as Antarctic scientists had argued for many years, NASA asserted that the nutritional and psychological value of fresh produce is “a solution to the challenge of long-duration missions into deep space.”

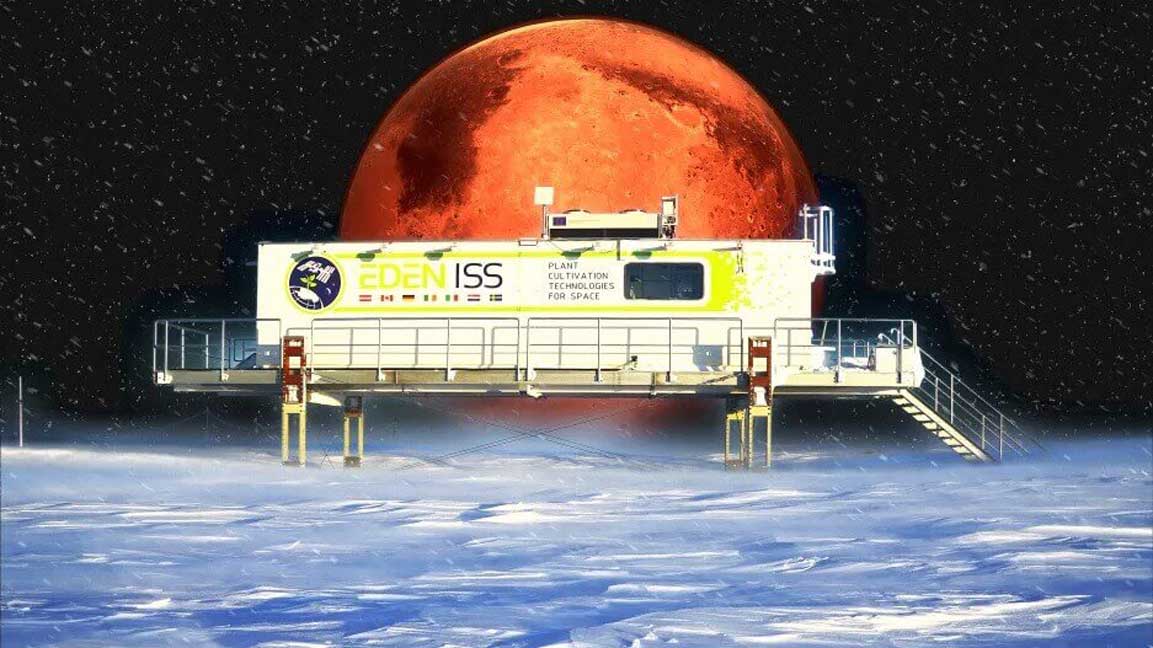

EDEN ISS is the newest experiment designed to mimic a food production facility on the Moon and can successfully feed a six-person crew. [Photo: DLR/Flickr]

Antarctic research plays an important role for space to this day. In 2018, Germany launched a project in Antarctica called EDEN ISS that focused on plant cultivation technologies and their applications in space in a semi-closed system. The plants grow in air, as misters spray chemically enhanced water on their roots. In the first year, EDEN ISS was able to produce enough fresh vegetables to comprise one-third of the diet for a six-person crew. Just as in Antarctic history, the question of how to grow plants is central to any discussion of possible human settlements on the Moon or Mars. People eventually abandoned efforts to cultivate the harsh Antarctic landscape for food production and turned to artificial technologies and environments to do so. But after over a century of practice and using the most modern techniques, the food grown in Antarctica has never been able to support many people for very long. Before sending people to the Moon or Mars, it might be wise to first prove that a settlement can survive on its own amid the frozen southern plains of Earth.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.