- | 9:00 am

Long hours, low pay: Are we taking delivery boys for a ride in the Middle East?

Delivery riders in the Middle East have become essential to whet the daily appetites of millions. But their working conditions are far from perfect.

It’s hotter than usual on a Friday night in June, and delivery rider Rafi is waiting for his next order. His day began at 7 AM, but at 8:30 PM, he says, he’s prepared to work until dawn to meet his daily quota.

He’s on a target set by the contractor that provides him with the motorbike and the visa that lets him live in the country. On average, he works a 17-hour day shift to make his minimum target of 10 deliveries.

“If we don’t meet these targets, we will get a penalty,” he says.

Adding to such a hectic schedule, petrol prices in the region are at an all-time high this month, too. “Without allowances or support, deliveries are hard to come by,” Rafi adds.

It’s been nearly a month since the food-delivery workers in Dubai have staged a mass walkout, calling for better pay and working conditions, but a Pakistani delivery rider, who wanted to keep his identity anonymous, says there has been no change in their work-life. “Our lives have become more miserable since then.” He adds that many workers who went on strike have either been deported, blacklisted, or are paying the penalty.

The story of Rafi is the everyday life of the millions of riders that make up the fleet of major delivery apps across the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Egypt, Oman and the region at large.

“The fact that our contractors sponsor our visas, they are the ones that decide everything and make the final decision. They charge us 50% of the premium amount for full-body insurance, amounting to approximately $163 of $326. But when we meet with an accident, we realize that we don’t have road insurance,” says another delivery rider, who requested anonymity to speak freely.

If a delivery rider earns $1,633 a month, their home country’s exchange valuation is magnified. Several delivery workers come to the Middle East to support their families back home. “We do all sorts of things — sell our property back home, our wives’ jewelry, in hopes of building a brighter future and good opportunities.”

But, it’s a distant dream given the exceptional working conditions of this job.

A delivery rider, who has worked for noon, Deliveroo, Talabat, and Careem, says that when the order is for far-off locations, “we reject it on the app and then, we’re blocked off as a corrective measure.” That’s not the best circumstance, especially when working on a commission model.

While some players, like Careem, provide a fixed salary for some and a commission model for others — the commission model is the overriding popular system that most earn.

Let’s consider a few numbers to understand the commission model.

A Dubai-based rider, Fahidi, said that a contractor will set targets of 300, 350, or 400 deliveries per rider in a month. “If we fail, there are repercussions.” Given inflation and fierce competition, the ability to work flexibly and secure orders have become increasingly difficult.

“We earn $2.04 per order,” another delivery rider explains. Working long hours in summers means braving a temperature that easily crosses 45 degrees in June. Yet, the heat is the least of the roadblocks in the life of a delivery rider.

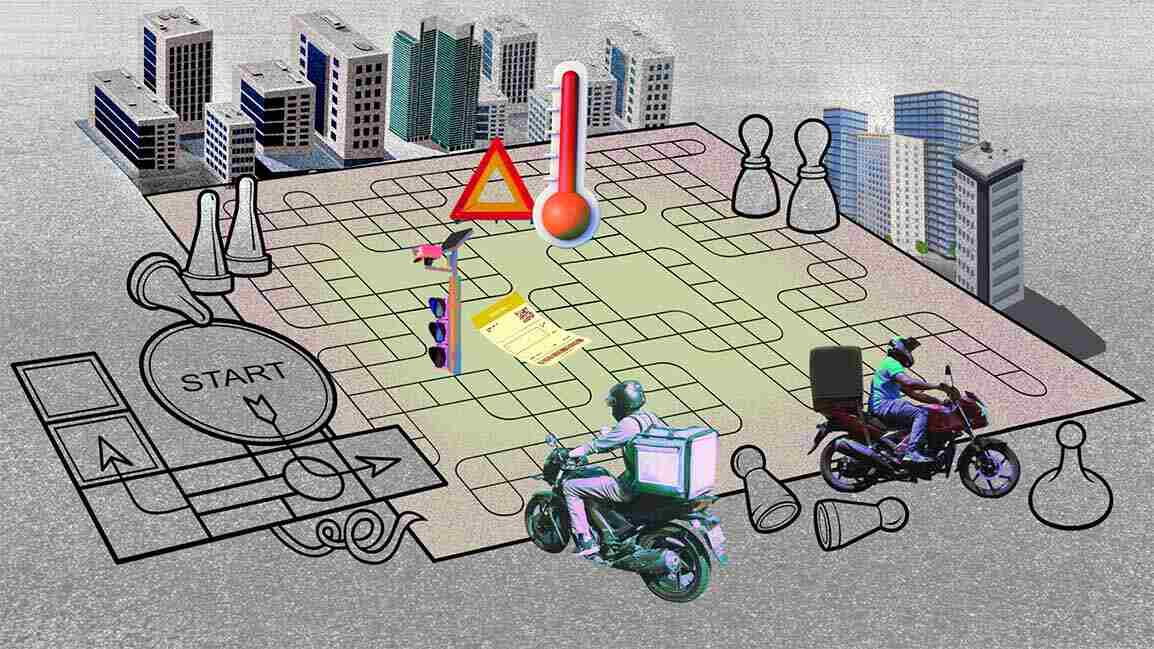

EVERYDAY ROADBLOCKS

There is low pay, but there is also a range. A rider at Talabat, one of the biggest delivery providers with a large fleet across the Middle East, earns approximately $2.04 per delivery. A Deliveroo rider earns an average of $2.86 per delivery. Careem, which is not solely focused on food, offers its riders $2.99 – $4.08 per delivery.

Fines for illegal parking are one of the biggest concerns as many restaurants do not have any designated parking spaces for delivery staff. “Fines are an everyday thing. Sometimes we end up paying $544 a month for parking. I have friends who have paid $1,905 in fines,” says Rafi.

Reminiscent of the days when Uber was new to the market, one rider says, “At that time, the rider’s well-being mattered. We were paid for our effort. If we drove extra miles, we were compensated fairly.”

Some delivery providers, such as noon, give allowances of $81.68 for petrol. But that may cover, at best, five days for a delivery rider in a month.

When asked about the biggest hurdles faced, Rafi says that along with the obvious challenges mentioned above, an unspoken but equally important challenge is the everyday roadblocks and prejudices. “Restaurants don’t let us enter their premises, 50% don’t let us use their washrooms, security guards tell us to use the service elevator or don’t let us enter the offices.”

“Some respect as a human would make a difference,” adds Rafi.

An anonymous source from a leading delivery company in the region said, “The sector has been entirely unorganized and dominated by a particular nationality. This trend went up about five years ago when there was a huge opportunity in the field. Someone may have started as a delivery rider but became entrepreneurs by floating their own companies and recruiting people from their country.”

The implication of mentioning this is that it was an unregulated sector. Without any policies, riders pay contractors a hefty amount when they come from their home countries but are paid just enough to barely cover their living expenses in this part of the world.

For blue-collar workers in the UAE or an average delivery rider, the salary ranges from $544 – $816 per month. If they work over time, say 14-15 hours, they can earn $952 to $1,089.

Talabat, Careem, and Deliveroo changed the market and popularized a per delivery model. Under this model, at least 30% to 40% of the riders could make $1,905 to $2,178 each, month on month, which is unheard of in this segment.

Earlier, delivery riders would migrate on a clerk or domestic help visa through contractors. None of them had insurance or guaranteed compensation.

The source explains that things have improved ever since the government addressed the delivery riders’ rights. But more needs to be done. “They need workmen’s compensation, insurance, and other incentives.”

While the online food delivery sector has grown with more than 200 contractors, the source adds, “the industry must consolidate, and change must come from the top. There needs to be a policy to ensure these riders are on the contractors’ visas, not freelance visas, as is the norm”.

RACE AGAINST TIME

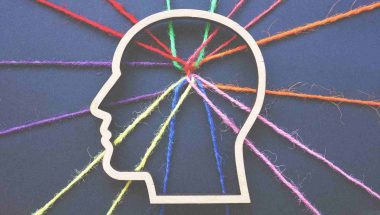

The well-being and safety of delivery riders have been a cause of concern for many because of their reckless driving habits. Thomas Edelmann, Founder & Managing Director of RoadSafetyUAE, conducted a study to understand the pain points of motorcycle riders. “It’s easy to lash out at these riders, but we wanted to understand their view of road safety,” he says.

“We found that only 50% of riders think that the customers don’t care about their safety,” says Edelmann. “A delivery rider delivering a pizza thinks customers are only concerned about receiving their order pronto without any concern about their safety.”

The food brands reiterate customers’ toxic expectations as they market themselves as delivering food as fast as possible. “They give you a guarantee of the fastest and shortest delivery. This puts a lot of pressure on the delivery boys because they almost kill themselves to deliver a pizza on time,” adds Edelmann.

KICK-STARTING THE CULTURE OF CARE

There are many opportunities for food delivery firms to change this expectation; they need to stop advertising the time element of the delivery, says Edelmann. “They should advertise that they’re looking at keeping the safety of riders at the top of priorities.”

Also, consumers have to be tied into the equation that they are interested in the well-being and safety of the delivery riders. “We need to ensure we remove the steam from the system because you see a delivery boy doing something crazy every day, but we need to understand why they’re doing it,” says Edelmann.

However, the industry will require much more than policy changes. “The real change has to come from the big brands,” he says, emphasizing the need for a new “culture of caring.” “If you promise 30 minutes delivery to a customer and he receives it in 33 minutes, three minutes could mean a lot to a rider”.

If we kick-start a culture change, we can break the reckless driving habit that many delivery riders exhibit on the roads. “Culture change must happen from the hands that feed them.” Other corrective measures from the public sector can only go so far but won’t result in behavior change.

“We’re also lobbying strongly for controlling the road behavior of riders. It’s a space that needs more technology. Think about an alarm in a taxi that goes off when a speed limit exceeds; RTA tracks every taxi. With delivery riders, this is not the case. They’re not monitored.”

He highlights several telematic solutions, such as black boxes, that can be used to monitor delivery workers. “We’re currently working on a trial, but the aim is to help riders understand that they cannot continue to speed,” says Edelmann. “But food brands and fleet operators have no interest in investing in safety measures because it costs money.”

In contrast to the stifling conditions of riders stand fancy hi-tech offices of food delivery apps, representative of a sanitized, albeit ironical, face of the food delivery business. Many of these big names in business have instituted best practices and incentive programs enabling talent retention amidst the Great Resignation. If only they extended similar benefits to delivery staff – so crucial to revenue generation – the food delivery world would be more equitable. But this is far from reality which is why the question remains: Why do these tech enterprises hide behind a contractor arrangement absolving them from any form of responsibility whatsoever?

Hence, awareness of all stakeholders, culture change at a brand level, and the role of technology are important factors in moving the industry forward. Meanwhile, Rafi sits at home, waits, and refreshes the app for now. He worries about how he will pay his rent and bills and send money to his family.

Note to readers: Names of sources are changed to keep their identities anonymous. Talabat and Careem were contacted to comment on the well-being of last-mile delivery workers, but we didn’t receive their responses at the time of publishing.