- | 9:00 am

Many CEOs are now making 670 times more than their company’s median-wage workers

At 49 publicly traded companies, the gap between what CEOs and median-wage workers earn is a 1,000-to-1 ratio.

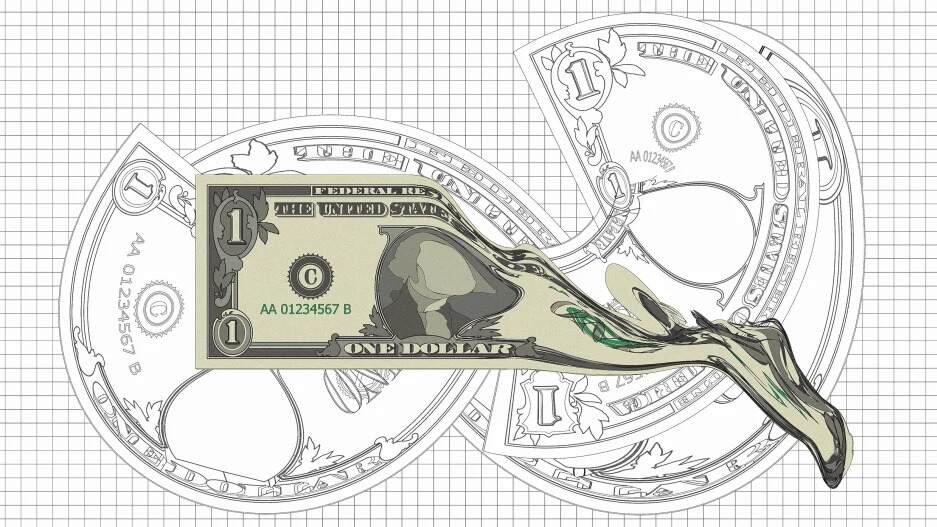

With multiple strikes, headline-grabbing unionization efforts, and reports of workers quitting due to low pay and poor working conditions, 2021 seemed like the “year of the worker.” But at the country’s largest low-wage employers, that trend of labor action didn’t translate into better worker pay. At the 300 publicly held U.S. corporations with the lowest median wages, the gap between what CEOs and median-wage workers earn has grown to a ratio of 670-to-1, according to a new report—up from 604-to-1 in 2020.

That’s just the average gap; the ratio at 49 of those 300 companies is larger than 1,000-to-1, according to the progressive think tank Institute for Policy Studies, which released its annual Executive Excess report on Tuesday. Since 1994, the institute’s researchers have looked at high levels of executive pay and how that pay affects inequality; the 2020 report detailed how CEO pay increased even as low-wage workers—particularly frontline, essential workers—lost hours, their jobs, and even their lives during the pandemic. This report, the institute notes, “extends the pandemic’s pay disparity story into 2021.”

“There’s been so much talk about how low-wage workers did have a bit more leverage in 2021, and might have gotten a bit of a raise, so we wanted to explore whether that had really happened,” says Sarah Anderson, who directs the Global Economic Project at the institute, coedits the institute’s website, Inequality.org, and is the lead author of the report. For this year’s Executive Excess report, researchers pulled the companies from the Russell 3000 list that had the lowest median pay in 2020, and then pulled 2021 data from proxy statements filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, focusing finally on 300 firms.

While CEOs at those 300 corporations saw their pay increase by $2.5 million in 2021—to an average of $10.6 million—median pay at those companies went up by only $3,556, to an average of $23,968. At more than a third of those firms, median pay didn’t even keep up with the 4.7% average inflation rate in 2021. “A lot of workers at these companies, in other words, lost ground, while CEO pay went through the roof,” Anderson says.

Anderson knows the counterargument some may make when seeing those statistics: that companies might not have had the extra cash to put into worker wages. “That’s why we looked at the stock buyback issue,” she says. At those 106 companies where worker pay didn’t keep pace with inflation, 67 companies—nearly two-thirds—spent resources buying back their own stocks, a tactic used to inflate the price of shares, and which then inflates executive stock-based pay.

These stock buyback purchases totaled $43.7 billion. In one example, the report notes that Lowe’s spent $13 billion on share repurchases—enough money that the company could have given each of its 325,000 employees a $40,000 raise. In reality, median pay at Lowe’s fell 7.6% in 2021, to $22,697. (A spokesperson for Lowe’s did not immediately respond to Fast Company‘s request for comment.)

“That really dramatizes the trade-offs here,” Anderson says. “We’re not talking about insignificant amounts of money; we’re talking about significantly draining capital that could be going to worker wages, or R&D, or other forms of investments that would arguably be a lot better for the company over the long term.”

Large gaps between CEO pay and that of median-wage workers have been shown to contribute to high turnover, lower job satisfaction, and negative employee morale. And it’s not just people at those companies who are affected; in some cases, taxpayer money funds the corporations that have these extreme gaps. Forty percent of the companies reviewed for this report received federal contracts between October 2019 and May 2022, totaling $37.3 billion. This is where government regulations can come into play, Anderson notes, such as conditions on federal contractors that make it more difficult for them to receive federal dollars if they have huge CEO-to-worker pay gaps. “It could help ensure that we get the best bang for the taxpayer buck,” she says.

President Joe Biden’s administration has shown some interest in reining in the pay gap. Last summer, Biden announced that some government contractors would have to pay their employees at least $15 per hour. His budget plan, announced in March, also addresses stock buybacks, with plans to require executives to hold on to their stock for three years after a buyback, so they aren’t selling their stocks in a multiyear period.

The American public supports such actions: A recent Just Capital poll found that 87% of Americans agree that the growing CEO-to-worker pay gap is “a problem for this country today,” and 70% agree that “there should be a maximum amount that CEOs are compensated relative to the average worker.”

Along with incentives for federal contractors and restrictions on stock buybacks, the institute’s report suggests that laws to raise taxes on companies with large CEO-to-worker pay gaps—two such laws are currently in place in San Francisco and in Portland, Oregon—could help reform this inequality. “The beauty of putting conditions that are tied to the pay gap,” Anderson says, “is that it’s an incentive to narrow those gaps both by lifting up the bottom and bringing down the top.”