- | 8:00 am

How MIT students are helping revitalize a tiny Italian village

A student program taps into local knowledge and concerns to revive rural Italian towns.

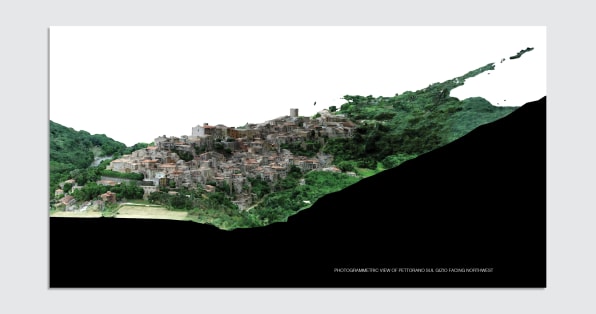

In a tiny hilltop Italian village two hours from Rome but a world away, a team of design students recently moved into an empty building and began plotting out the future.

Pettorano sul Gizio, population 1,500, is like many towns across central and southern Italy in that its main industry, agriculture, is both essential to modern society and nearly forgotten by it. Nearby towns in this region, Abruzzo, have the feeling of being left behind by the times. But they can’t yet be counted out. The state-run rail company has recently been rehabilitating lines in this area, and agriculture is still economically viable. Add in the region’s modest tourist appeal among hikers and skiers, the rise of remote working, and programs focused on resettling refugees in places that could bounce back, towns like Pettorano have the makings of a new kind of rural economy. The student design team wanted to figure out how to get there.

The program was a pilot from Liminal, a nonprofit research group focused on the sustainable development of small towns. Founded by graduates from Harvard and MIT, Liminal is now based in Italy and is focused on the small, sometimes ancient towns and villages that have been drained of human and financial resources by urbanization and industrialization.

With funding from MIT-Italy and a partnership with FS Fondazione, the state rail company’s nonprofit arm, Liminal brought 18 architecture and urbanism students from MIT to Abruzzo for a three-week immersion in the region, to learn about local priorities and develop design visions for the future of its small towns. Working directly with a range of stakeholders, from regional government representatives to the people tilling the fields, the students examined regional issues through the lenses of urban planning and architecture. They encountered challenges inextricably linked with the region’s territory—from abandoned buildings to fragmented farms to underdeveloped tourist infrastructure.

“These problems are always looked at from a distance,” says Ginevra D’Agostino, president of Liminal. “That distance can help in some cases, but sometimes you really need to get on the ground and do field work to actually be able to understand where the real opportunities are.”

The students’ work commenced in June. An old train station was converted into a pop-up coworking space, where the students met with locals and began translating their findings into designs and visions.

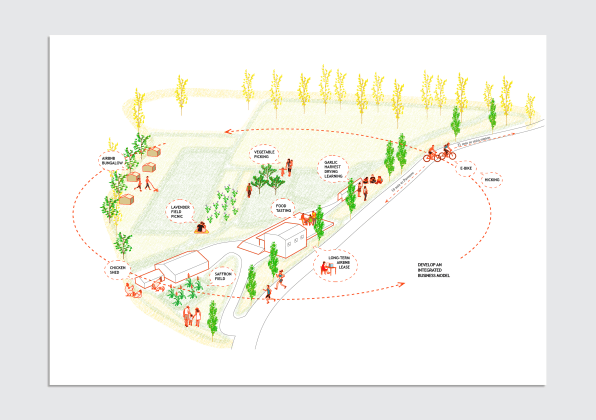

The students were divided up into six groups of three, and each took on a different aspect of the region’s development challenges. One looked at the rail line connecting several towns in the area as a means of improving local and economic connections. Another focused on a single station’s potential to serve as a hub for both tourists and locals. Others narrowed in on improving the viability of agriculture, and tapping into a refugee resettlement program that could boost the population and the agricultural workforce.

A partly dilapidated network of trails between the towns was a rich focus area. Working with a subgroup of the national Alpine Hiking Club, the students documented trails that had previously been unmapped and strategized ways to create the tourist infrastructure needed so that towns near them could benefit from visiting hikers. In conjunction with local town officials, the students outlined ways to improve trail-based tourism, from the potential for a baggage transport startup to ideas for hikers’ accommodations. “They were asking, do we need Airbnbs, and with what kind of qualities, or hotels, or bed and breakfasts? Do we need signage?” says Nicolás Delgado Alcega, cofounder of Liminal. “All of these questions, the locals don’t know the total list of them or what they’re going to need funding for, but they know there’s a lot of these technical things to overcome.”

A different group also used mapping techniques to help understand and quantify the ways individual villages are losing population, even if official census figures show upward population trends at the regional level. “They can’t access funding because the data says they’re experiencing growth,” Delgado Alcega says.

“This is a condition that many other towns are experiencing. So this is something that can be used by many other towns,” D’Agostino adds. The group estimates that 70% of Italy’s land is made up of towns with populations below 6,000.

All the research conducted this summer will be used to help underpin grant proposals and other strategic plans for the towns, and this work will also be exhibited during the next Venice Architecture Biennale. D’Agostino says some plans will be submitted for approval this fall, and Liminal will be partnering with groups and town officials to pursue other funds to bring the design visions to reality.D’Agostino says Liminal has already helped secure more than $1 million in grants for other towns in Italy, and she hopes to expand this student program for similar design exercises in the future. Delgado Alcega says working with local stakeholders will continue to be essential to Liminal’s work. “It’s not like where do we find the urban problems regardless of whether they can be solved or not,” he says. Instead, the students learn on the ground and directly from locals about what realistic visions exist “and then try to give them shape, which is what designers do.”