- | 4:00 pm

Why Amazon’s “dead grandma” Alexa is just the beginning for voice cloning

The evolution of text to speech technology is bringing us closer to convincingly human-sounding voices.

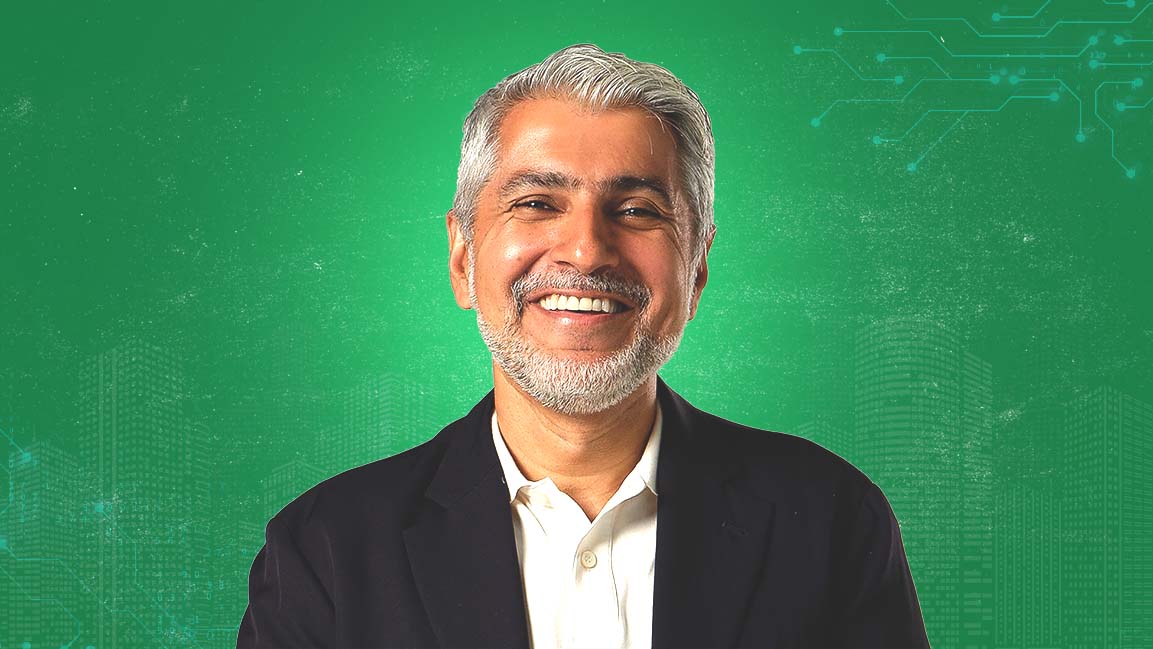

Earlier this summer, at the re:MARS conference—an Amazon-hosted event focusing on machine learning, automation, robotics, and space—Rohit Prasad, head scientist and vice president of Alexa A.I., aimed to wow the audience with a paranormal parlor trick: speaking with the dead. “While A.I. can’t eliminate that pain of loss, it can definitely make their memories last,” he said, before showing a short video that starts with an adorable boy asking Alexa, “Can Grandma finish reading me The Wizard of Oz?”

The woman’s voice that reads a few sentences from the book sounds grandmother-y enough. But without knowing Grandma, it was impossible to evaluate the likeness. And the whole thing struck many observers as more than a little creepy—Ars Technica called the demo “morbid.” But Prasad’s revelation of how the “trick” was performed was truly gasp-worthy: Amazon scientists were able to summon Grandma’s voice based on just a one-minute audio sample. And they can easily do the same with pretty much any voice, a prospect that you may find exciting, terrifying, or a combination of both.

The fear of “deepfake” voices capable of fooling humans or voice-recognition technology is not unfounded—in one 2020 case, thieves used an artificially generated voice to talk a Hong Kong bank manager into releasing $400,000 in funds before the ruse was discovered. At the same time, as voice interactions with technology become more common, brands are eager to be represented by unique voices. And consumers seem to want tech that sounds more human (although a Google voice assistant that imitated the “ums,” “mm-hmms” and other tics of human speech, though, was criticized for being too realistic).

That’s been driving a wave of innovation and investment in A.I.-powered text-to-speech (TTS) technology. A search on Google Scholar shows more than 20,000 research articles on text-to-speech synthesis published since 2021. Globally, the text-to-speech market is projected to reach $7 billion in 2028, up from about $2.3 billion in 2020, according to Emergen Research.

Today, the most widespread use of TTS is in digital assistants and chatbots. But emerging voice-identity applications in gaming, media, personal communication, are easy to imagine: custom voices for your virtual personas, text messages that read out in your voice, voiceovers by absent (or deceased) actors. The metaverse is also changing the way we interact with technology.

“There are going to be a lot more of these virtualized experiences, where the interaction is less and less a keyboard, and more about speech,” says Frank Chang, a founding partner at A.I.-focused venture fund Flying Fish in Seattle. “Everyone thinks of speech recognition as the hot thing, but ultimately if you’re talking to something, don’t you want it to just talk back to you? To the extent that that can be personalized—with your voice or the voice of somebody you want to hear—all the better.” Providing accessibility for people with vision challenges, limited motor function, and other cognitive issues is another factor driving development of voice-tech, notably for e-learning.

Whether or not you like the idea of “Grandma Alexa,” the demo highlights how quickly A.I. has impacted text-to-speech, and suggests that convincingly human fake voices could be a lot closer than we think.

The original Alexa, released with the Echo device in November 2014, is believed to have been based on the voice of Nina Rolle, a voiceover artist based in Boulder (something neither Amazon nor Rolle ever confirmed), and relied on technology developed by Polish text-to-speech company Ivona, acquired by Amazon in 2013. But the early Alexa’s conversational style left a lot to be desired. In 2017, VentureBeat wrote: “Alexa is pretty smart, but no matter what the A.I.-powered assistant talks about, there’s no getting around its relatively flat and monotone voice.”

Early versions of Alexa used a version of “concatenative” text-to speech, which works by compiling a large library of speech fragments recorded from a single speaker, which can be recombined to produce complete words and sounds. Imagine a ransom note, where letters are cut up and pasted back together to form new sentences. This approach generates intelligible audio with an authentic-sounding timbre, but it requires many hours of recorded voice data and lots of fine-tuning—and its reliance on a recorded library of sounds makes it difficult to modify voices. Another technique, known as parametric TTS, doesn’t use recorded speech, but rather starts with statistical models of individual speech sounds, that can be assembled into a sequence of words and sentences and processed through a speech synthesizer called a vocoder. (Google’s “standard” Text-to-Speech voices use a variation of this technology.) It offers more control over speech output, but has a muffled, robotic sound. You wouldn’t want it to read you a bedtime story.

In the effort to create new, more expressive and natural-sounding voices, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Baidu, and other major players in text-to-speech have all in recent years adopted some form of “neural TTS.” NTTS systems use deep-learning neural networks trained on human speech to model audio waveforms from scratch, dynamically converting any text input into fluid-sounding speech. Neural systems are capable of learning not just pronunciation but also patterns of rhythm, stress, and intonation that linguists call “prosody.” And they can pick up new speaking styles, or switch speaker “identities,” with relative ease.

Google Cloud’s Text-to-Speech API currently offers developers 100-plus neural voices in languages ranging from Arabic to Vietnamese (plus regional dialects) along with “standard voices” that use older parametric TTS (listen here). Microsoft’s Azure gives developers access to more than 330 neural voices across 110-plus languages and dialects, with a range of speaking styles—including newscast, customer service, shouting, whispering, angry, excited, cheerful, sad, and terrified (try it out). Azure neural voices have also been adopted by companies including ATT, Duolingo, and Progressive. (In March, Microsoft completed its acquisition of Nuance, a leader in conversational A.I. and a partner in building Apple’s Siri, whose Vocalizer service offers 120-plus neural chatbot voices in over 50 languages.) Amazon’s Polly text-to-speech API supports roughly three dozen neural voices in 20 languages and dialects, in conversational and “newscaster” speaking styles(listen to an early demo here.

The technology underlying the Grandma voice demo was developed by scientists at Amazon’s text-to-speech lab in Gdansk, Poland. In a research article, the developers describe their novel approach to cloning a new voice from a very limited sample—a “few-shot” problem, in machine-learning parlance. Essentially, they split the task into two parts. First, the system converts text into “generic” speech, using a model that’s been trained on 10 hours of speech from another speaker. Then, a “voice filter”—trained on a one-minute sample of the target speaker’s voice—imparts a new speaker identity, modifying characteristics of the generic voice to sound like the target speaker. Very few training samples are needed to build new voices.

Rather than having to build a new text-to-speech model for each new voice, this modular approach turns the process of creating a new speaker identity into the computationally easier task of changing one voice into another. On objective and subjective measures, the quality of synthetic speech generated in this way was comparable to speech from models trained on 30 times more data. That said, it can’t fully mimic a specific person’s speaking style. In an email to Fast Company, the Alexa researchers explain that the voice filter only changes the timbre of the speaking voice—its basic resonance. The prosody of the voice—its rhythms and intonation—come from the generic voice model. So, it would sound like Grandma’s voice reading, but without the distinctive way she’d stretch out certain words or take a long pause between others.

Amazon won’t say when the new voice cloning capabilities will be available to developers and the public. In an email, a spokesperson writes: “Personalizing Alexa’s voice is a highly desired feature by our customers, who could use this technology to create many delightful experiences. We are working on improving the fundamental science that we demonstrated at re:MARS and are exploring use cases that will delight our customers, with necessary guardrails to avoid any potential misuse.“

One can imagine offering the ability to customize something like Reading Sidekick—an Alexa feature that lets kids take turns reading with Alexa—with a loved one’s voice. And it’s easy to see how the “Grandma’s voice” demo might presage an expanded cast of more adaptable celebrity voices for virtual assistants. Alexa’s current celebrity voices—Shaquille O’Neal, Melissa McCarthy, and Samuel L. Jackson—required about 60 hours of studio recordings to produce, and they’re somewhat limited in what they can do, answering questions about the weather, telling jokes and stories, and responding to certain questions, but defaulting to the standard Alexa voice for requests outside the system’s comfort zone.

Google Assistant “celebrity voice cameos” by John Legend and Issa Rae—introduced in 2018 and 2019, but not currently supported—similarly combined prerecorded audio with some impromptu responses synthesized with WaveNet technology. The ability to develop more robust celebrity voices that can read out any text input after a short recording session could be a game changer—and might even help boost stagnating sales of smart speakers. (According to research firm Omdia, the U.S. smart speaker shipments were down nearly 30% last year relative to 2020, including a nearly 51% drop in Amazon Alexa smart speaker shipments.)

As the big tech companies continue to invest in text to speech, one thing is certain: It will be harder and harder to tell if the voice you’re hearing is made by a human, or by a human-made algorithm.