- | 7:00 am

This 17-year-old is using fish waste to clean up heavy metal pollution

Rise, a program from Schmidt Futures, awards young students who are solving global problems.

When she was in seventh grade, Jacqueline Prawira launched a five-year project to design a bio-based alternative to plastic, eventually using upcycled fish-scale waste to make it. Last year, before she became a high school senior, she started using the same material to tackle another problem: how to clean up heavy metals in wastewater.

She discovered that the collagen and calcium salts in the scales can act like a magnet for heavy metal pollution, capturing it so it can later be recycled. “Nature already has the components that are primed to react and essentially bond with heavy metals, and can remove those heavy metals from water in the environment,” she says. Right now, wastewater treatment plants may not necessarily take out heavy metals before dumping water in rivers (the EPA doesn’t require this, though states sometimes do), despite the fact that the contamination can be toxic in drinking water.

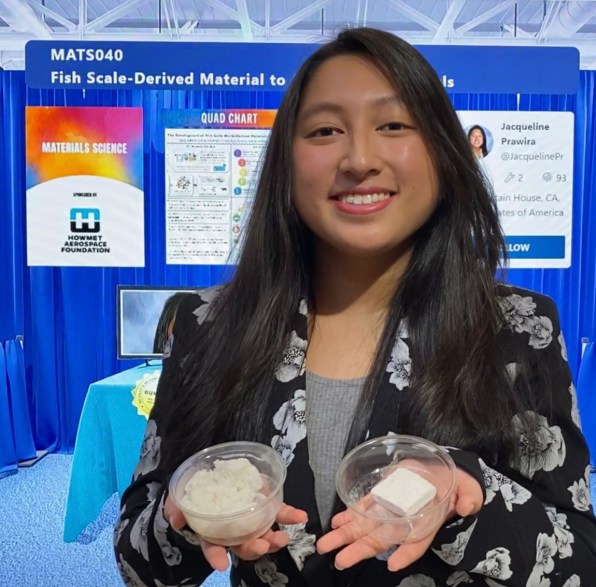

Jacqueline Prawira [Photo: courtesy Jacqueline Prawira]

Prawira, now 17 and beginning her freshman year at MIT, is one of 100 winners of the second cohort of Rise, a program from Schmidt Futures and Rhodes Trust designed to support young students not just early in their careers, but potentially for the rest of their lives. “Human beings are hardwired to get excited about instant results,” says Eric Braverman, CEO of Schmidt Futures, a philanthropic venture cofounded by Schmidt (former CEO of Google) and his wife, Wendy Schmidt. “But our hard problems in science and society are not going to get solved overnight.” The program offers scholarships to students whose tuition isn’t covered by financial aid, along with a three-week summit, and courses like human-centered design. The students also will receive ongoing mentorship and funding opportunities later in their careers.

The list of winners includes a student from Vietnam who used microfluidics to build a prototype of a cancer-detecting toothbrush; another American student who built a brain-computer interface to help stroke victims recover; and a student from Nigeria who designed a program to help train educators to better teach computer science in Nigerian schools.

The program aims to find brilliant problem solvers who might need an extra hand to keep working on global challenges. “I think we’re living in a moment of real contrast: We have more tools than ever to solve hard problems . . . but we have problems that are bigger and more complex than ever,” Braverman says. “Economic disparities are rising. The planet seems to be burning. And so the question is, What is it going to take to solve these hard problems? Our view is that it’s going to take human ingenuity, like it always has. But the most important thing we can do to ensure that people can solve the problems that are important to the world is to get everyone to the table. And then keep them there.”

Prawira, for example, could apply later for funding from Schmidt Futures to help continue her research and make her product, Cyclo.Cloud, a reality at wastewater treatment plants or in households in developing countries. Her research has found that the solution she creates from fish scales can absorb up to 82% of heavy metals from water. That increases to 91% if the treatment is combined with electrolysis. A kilogram of her product, at a cost of 23 cents, can clean up 1,000 liters of water contaminated with heavy metals. “It would be a dream come true for my invention to become a reality,” she says.