- | 9:00 am

Can Middle East designers bring zen to spaces with Japanese aesthetics?

There is beauty and tranquillity in Zen gardens that Middle East designers can emulate.

Digital screens-–at least any time soon—won’t be replacing the authenticity of nature. Trees, sweet-smelling shrubs, and a watercourse near a well-trampled grass are pleasant, but a slight regulation of nature, something the Japanese have honed in their aesthetics, like the Zen garden, is a respite.

Japan has a subtle approach to design that can inspire harsh desert environments—an attentive approach to how Japanese Zen gardens are carefully outstretched and maintained can be an invaluable asset to learn and apply.

Due to many historical and cultural influences, Japanese designers have revered nature and the space that frames it. They dedicate their attention to the missing or the space between elements, which could be applied in Middle Eastern countries.

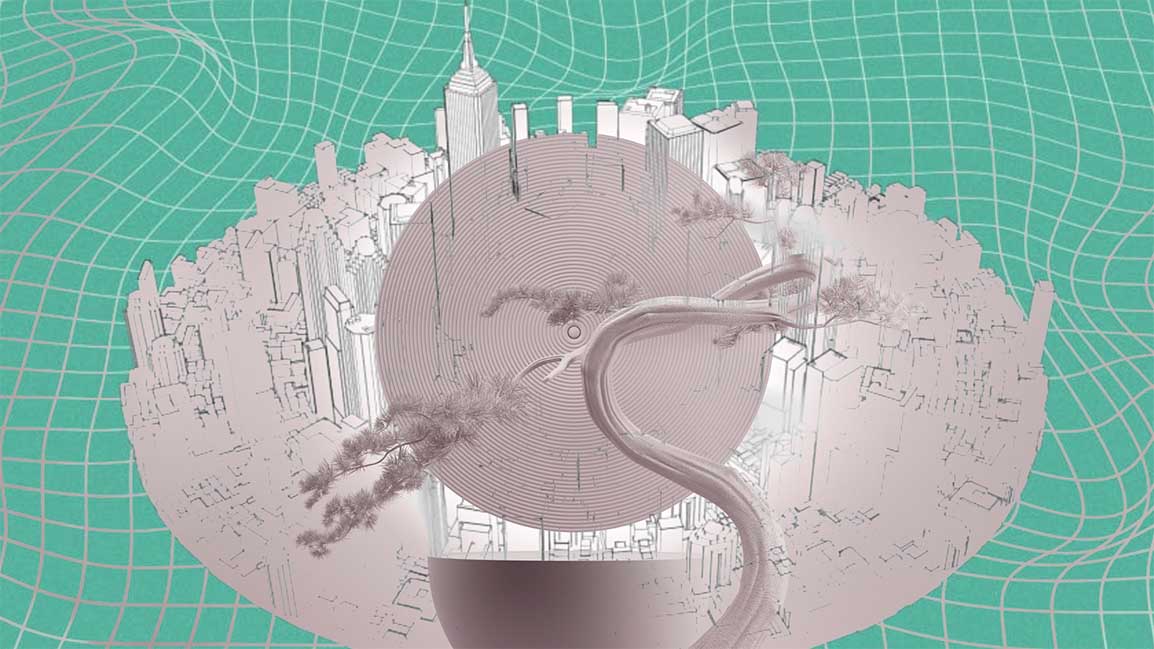

Internal ventilated spaces can be an alternative solution to recreate a miniature version of the desired scenery to evoke nature’s grandeur, just like in a Japanese Zen garden.

That means moving away from the typically centered round fountains toward accurately mimicking the oceans, rivers, mountains, and hills in interior spaces.

“Due to harsh weather conditions, private homes in Kuwait play an important social role as a meeting place for family and close friends. The interior landscape, gardens, and internal courtyards are part of the lifestyle,” said Nasser Abulhasan, Principal and Founding Partner at Kuwait-headquartered AGi architects.

ENHANCING AND PROTECTING NATURE

Relative to the flawlessly pruned symmetric gardens of the West, which Middle Eastern designers might be inclined to copy, Japanese gardens attempt to reproduce nature, offering a more natural order. A stone laid down horizontally represents an island, whereas a stone placed vertically aims to bear a resemblance to a mountain. Trees and plants represent forests and mountains. White gravel mimics the oceans. Rocks cautiously arranged in a declining manner could represent waterfalls.

Imagine the possibilities of exterior landscape arrangements and internal courtyard concepts with a deep understanding of nature in the Middle East.

“Project in Latin is ‘proiectare,’ which means to throw something ahead. We need to think in advance. We want to urbanize as little as possible, but at the same time, we want to enhance nature and protect it,” said Giovanna Carnevali, the Italian executive director of urban planning at NEOM. The 9 million people-accommodating, 170 kilometers-spanning Line project in Saudi Arabia’s NEOM was able to manifest a similar ambitious attitude successfully.

The project reinforces the idea that an introverted habitat might be necessary to flourish-–in an urban sense—if the external environment is unaccommodating. That resembles internal Japanese courtyards, conceptions of magnificence that ascend in the breathing pockets of longitudinal Machiya houses and at the sides of temples and Shinto shrines.

RESPECTING THE LOCAL CONTEXT

In the Japanese context, a sliding Shoji screen made out of a wooden grid and washi paper may gracefully frame a garden view resulting in a peaceful interior space. In a Middle Eastern scenario, one could imagine the screen’s grid label replaced by an Arabesque pattern, overlooking a garden that replaces a Japanese stone lantern, for instance, with an oversized fanous, with Japanese bamboo trees replaced by local plants and rocks.

The white gravel could be replaced by the soft sand of the desert, raked in a way that inspires the motion of the seas. One could then sit on a Persian carpet as opposed to a tatami mat, contemplating the view ––and oneself– through the tailored splendor.

“Japanese Zen gardens can be a source of inspiration. The most important thing is the need to respect the local context and introduce native vegetation or those appropriate for the specific climatic conditions in which we find ourselves, as well as the best solutions to get an efficient and low maintenance garden,” said Abulhasan.

“We must look for tailor-made solutions and take advantage of the potential offered by the existing environment. Arid climates represent a challenge and an extraordinary opportunity to implement comprehensive strategies. The vegetation is a powerful climate control strategy that acts as a natural barrier to reduce high temperatures and dust, and contributes to creating pleasant and relaxing spaces,” he added.

Following the selection of elements, special attention is dedicated to what is often an overlooked component in a Japanese Zen garden: arrangement; how each rock is placed, directed, and sequenced; and the overall achievement of balanced asymmetry. Borrowing elements from a Japanese Zen garden can enthuse a Babylon-like garden concept that could distill Middle Eastern cultural values and be exclusive to Arabian culture.

Nevertheless, some may have a contrasting perspective: “I disagree with the narrative that mandates rolling out the green carpets because I don’t consider the desert an unfortunate byproduct. The desert is a unique landscape,” says Reem Fayyad, the co-founder of GreenAtelier.

Part of the local ritual in the emirates is spending bonding hours, often on a winter weekend, among friends, adds Fayyad. “A desert is a dynamic place that changes day by day. Revisiting a view from the same spot guarantees a varied perspective every time. Hills relocate, and different parts of the city are exposed. I would open up my projects to the desert and invite native plants inside when possible.”

The patterns of a desert can be considered abstract art. Unlike a fixed landscape, the desert continually swings, making it an exciting territory. Fayyad considers the desert an empty template, lacking obstacles such as streets, buildings, and trees. Perhaps our mental landscapes mirror the empty desert in its presence, making the field an intellectually-clearing, problem-dissolving, anxiety-unpacking habitat.

Borrowing the intellectual attitudes of other cultures in design and aesthetics is a pursuit of growth. One could preserve the locality’s uniqueness while borrowing external tools to sharpen the saw.

Some of the best lessons from Japanese aesthetics, particularly inscribed in its Zen gardens, are its appreciation of emptiness by nurturing meaning from gravel or rocks, its meticulous arrangement, cautious sequencing, and thoughtful proportions, from which future landscape developments in the Middle East can benefit.