- | 8:00 am

Could these dirty ‘probiotic tiles’ make buildings healthier?

These tiles are porous, imperfect, and full of microbes.

Richard Beckett has an unusual background and an unusual mission. Before turning to architecture, the associate professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London trained in physiology and in biochemistry. Now, he wants you to know that microbes are our friends.

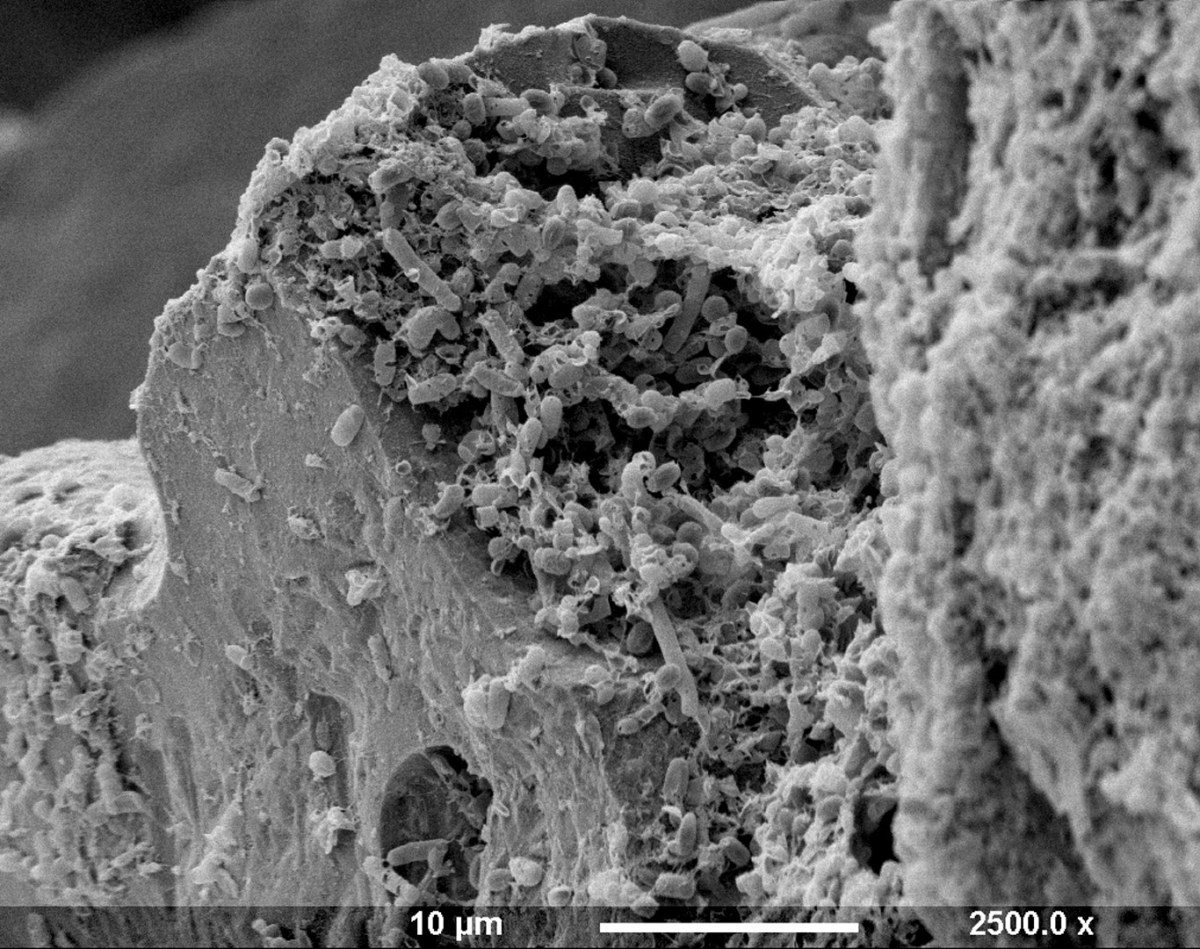

Beckett’s research is currently on display in the exhibition, Small Space in the City, at Roca London Gallery. There, he has taken over a booth the size of a desk and lined its walls with a dozen “probiotic tiles” made of recycled concrete and mixed with soil from a Finnish forest. Compared to the smooth and glazed tiles you may find at Bed Bath & Beyond, these tiles are porous, imperfect, dirty even; and Beckett says they will shed some soil if you rub them hard enough.

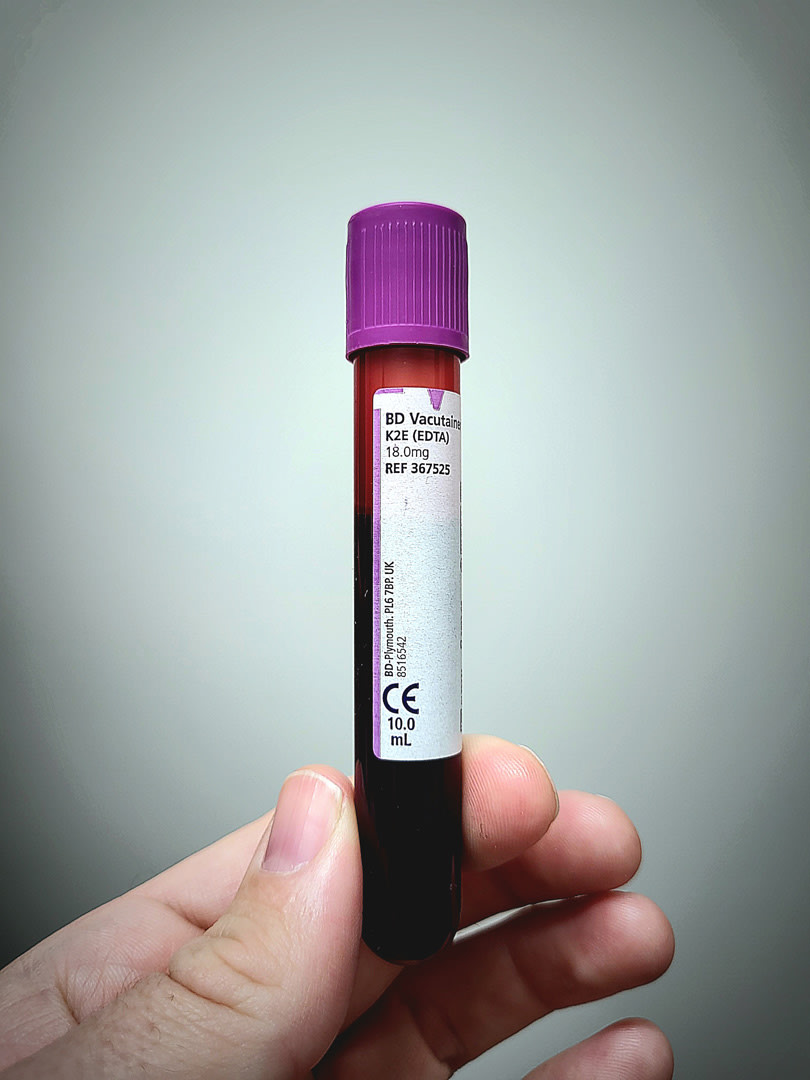

By his estimate, the soil contains “millions of microbes” with multiple strains, fungi, protozoa, “and probably a few harmful bacteria as well, but only in small amounts,” he says. Over the next few weeks (first at Roca, then in his studio at Bartlett), the architect will sit in a small, enclosed space, in close proximity to these tiles. And because the tiles are porous, he expects that airflow will help them shed some of the microbes onto or near his body. Throughout the experiment, an immunologist from University College London will be taking blood samples to understand the effects these microbes are having on Beckett’s immune system.

I first spoke with Beckett in early 2020, when those of us who had the luxury to barricade ourselves at home had done exactly that, while adopting hygiene practices that made everyone look like a germaphobe. Back then, when my hygiene radar was in overdrive, it was difficult to envision a world in which we would surround ourselves—on purpose—with microbes. (COVID-19 is a virus, not a bacterial infection, but both are synonymous with illness.) But the more Beckett spoke, the more it started to make sense.

There are good and bad microbes. We humans usually have both kinds in our bodies at all times; this combination of microbes is called a microbiome. When you get an infection, bad microbes take over and knock you out of balance. When you eat enough Bulgarian yogurt (no, really), you ingest good microbes, thanks to the probiotics found in it.

Various studies have shown that microbial exposure can help strengthen our immune system and protect children from developing asthma and other allergies. This kind of exposure is particularly true at early ages, but Beckett says our microbiome is constantly changing, so there is potential for similar benefits later in life too. “Through living next to [microbes] and being next to them, you get them on your skin, you breathe them, they populate your microbiome,” he told me on a more recent call. “Those kinds of exposures are the ones that we need for our immune systems to be constantly tested, and when your immune system is not tested regularly on these small levels, it becomes lazy and it doesn’t regulate itself.”

For now, the science isn’t clear on the exact parameters of that exposure (how much, for how long, etc.). But a 2020 study of 75 children in Finland showed that when they were exposed to a wider range of microbes in their environment, their microbiome changed and their immune system improved. That study was done across 10 playgrounds in 10 daycare centers, so it was done outside; but no one has done it inside, says Beckett.

For the Roca exhibition, the architect has partnered with Uute Scientific, a Finish company that makes a “microbiome restoring” ingredient—essentially ground-up soil extract—that is sourced from local forests then used in cosmetics, textiles, children’s toys, and now architectural tiles. He then mixed about 10% of that powder into a concrete mix and cast it in various 3D-printed molds.

The point, of course, is to create more surface area for the microbes to live on—and to provide an antithesis to the clean white walls of modernism—though Beckett notes has no plans to bring these tiles to the market as they remain a research project.

At the same time, the architect admits that his experiment is closer to an artistic provocation than a scientific study, but he is hopeful that even this kind of data will help him get further funding to study the correlation between microbes and immune health. “I’m convinced that architecture needs to be more biological,” he says. “We have completely gotten used to this antibiotic mentality in that life is safer if we just kill microbes, but we clearly know that’s not the case.”

The antibiotic mentality Beckett is referencing was born after Louis Pasteur’s germ theory and the discovery of viruses in the 1890s. Suddenly, cluttered interiors and soft fabrics were seen as breeding grounds for germs. Carpets in bathrooms made way for tile, and modernist architects became obsessed with white walls, which suggested cleanliness.

The invention of penicillin and other antibiotics in the 1930s then led to what Beckett describes in a 2020 paper as a “new wave of confidence over the threat of infection” and a preference for an “artificial indoor climate, sealed from the outside.”

In recent years, particularly since the pandemic, architects and developers have come to understand the value of good ventilation and a direct connection to nature. But Beckett wants to push this movement even further. He wants to bring nature, with all its flaws and all its imperfections (read: microbes) indoors. The real question is, how much convincing is that going to take?