- | 1:08 pm

Hemp can be used to make rebar that’s just as strong as steel

When a 12-story condominium building suddenly collapsed last June in Surfside, Florida, one reason was was hiding deep inside the structure. Within its concrete foundation, walls, and floors was a critical but risk-prone building material: steel reinforcing bar. In the aftermath of the collapse, investigators found this material to have extensive corrosion—enough to cause the massive building to simply fall apart.

Steel reinforcing bar, or rebar, is a key part of the way buildings like that condo tower are built, and it is critical to their structural integrity. But steel rebar is also susceptible to the moisture that can wind its way through concrete, causing largely invisible corrosion that can lead to structures collapsing almost without warning.

[Image: Alex Tsamis/courtesy Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute]

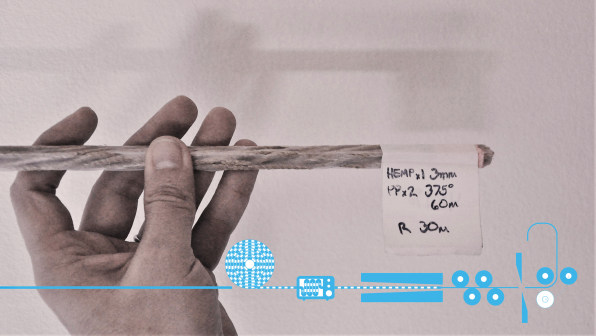

A team of researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) has an alternative. Instead of using steel to reinforce concrete, they’ve developed a composite reinforcing material made of surprisingly strong hemp fiber. Their hemp-based rebar uses the hearty fibers of the hemp stalk in combination with a resin or bioplastic to form bars that can safely replace steel rebar in concrete construction.

[Image: Alex Tsamis/courtesy Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute]

“There are some natural fibers that have a similar strength to steel for the same weight,” says Alexandros Tsamis, a professor of architecture at RPI. Synthetic materials like carbon fiber and fiberglass have such strengths, and so does hemp. When combined with plant-based bioplastic, hemp rebar could be an all-natural alternative to steel rebar. “Instead of extracting it from the earth, you grow it,” Tsamis says.

[Image: Alex Tsamis/courtesy Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute]

The scale of the material’s potential is massive. Steel rebar is everywhere, from sidewalks to skyscrapers. “It’s pervasive in any concrete structure. They’re just full of rebar,” says Dan Walczyk, a professor of mechanical engineering at RPI. “And it’s millions, if not billions, of dollars of construction material annually.”

[Photo: Dan Walczyck/courtesy Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute]

Eliminating steel from concrete construction could eliminate the corrosion risk that brought down the condo in Florida. With less corrosion, the concrete in buildings and bridges could last decades longer. “By switching the material used in one object from steel to a composite of fibers, you can drastically reduce the carbon footprint of the building industry, because you extend the lifetime of structures,” says Tsamis.

[Image: Alex Tsamis/courtesy Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute]

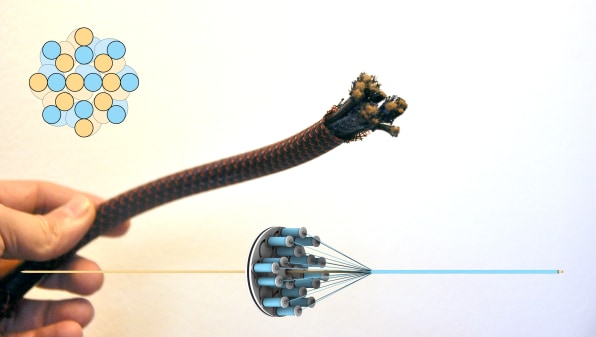

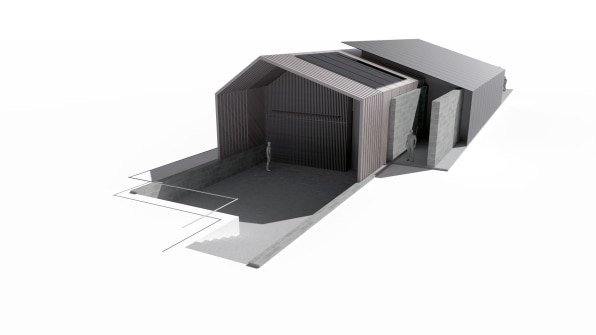

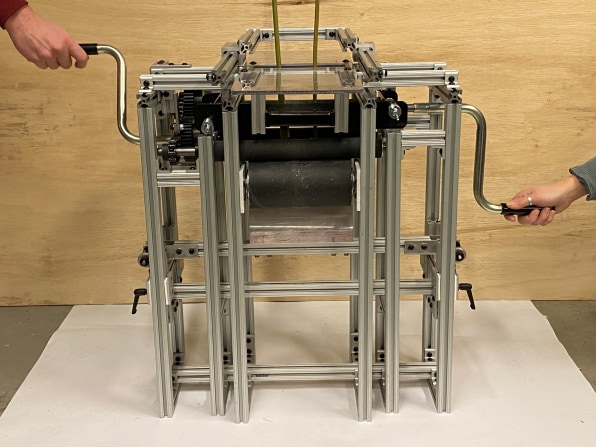

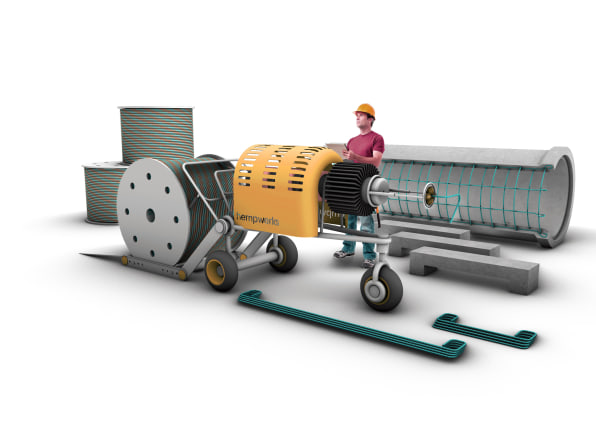

Hemp rebar and the machinery to make it are being developed by Tsamis and Walczyk, alongside architecture student Daniel Cohen and mechanical engineering student Sharmad Joshi. Tsamis equates the technology to 3D printing, which requires both a filament and a machine to form it. The filament for hemp rebar is a combination of extracted hemp fibers wrapped in a thermoplastic that is then wound into a rope-like coil. The machine, which the team is currently building into a proof of concept, is a car-sized device that pulls in that coiled material, heats it, and consolidates it into hardened bars. Tsamis says the machine is being designed to work on-site during construction projects, allowing for the hemp rebar to be made as needed. A specially fitted die can form the rebar based on the construction project’s needs, even bending it into complex shapes that would otherwise be done on site by construction workers.

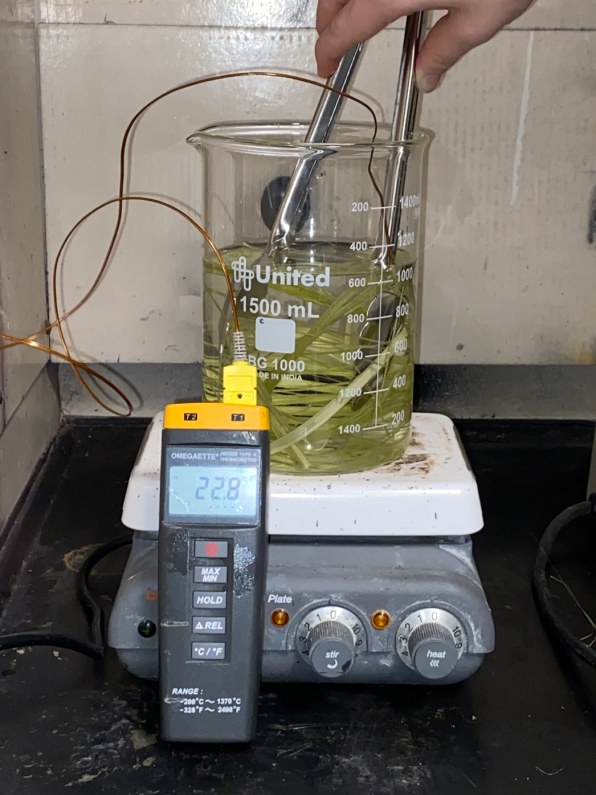

It may sound advanced, but the material is not particularly complicated to manufacture, according to Tsamis, who notes that the project started during the pandemic when the university’s labs were closed. “The first experiments that we did with consolidating happened in kitchen ovens,” Tsamis says. “And the first ropes we were making by hand. I had my son pull the other side of the rope I was making at my desk. My student’s cat was chewing on the rope while he was making his own version. So the beginnings of it were pretty modest in terms of the technology we had available.”

[Photo: courtesy Daniel Cohen]

Some challenges remain, though. Walczyk says the U.S. is behind other countries when it comes to the production of industrial hemp, which was only legalized in 2018. Bioplastics are also relatively novel. “There’s a lot of uncertainty in where these materials are coming from,” says Walczyk. “If we were to develop this technology in the next two weeks, we don’t necessarily have the material supply chain for it.”But once the material is available, Tsamis says it wouldn’t be very complicated for the building industry to swap out its steel rebar for the hemp-based variety. “People already know how to work with it. All the construction methods and all the know-how is there,” says Tsamis.

[Photo: Dan Walczyck/courtesy Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute]

The researchers say hemp rebar is probably still a few years away from getting into a building, but they’re already in talks with several large construction companies about how the material could be integrated into new projects. Walczyk says state or federal funding would help accelerate the development of the technology, and Tsamis says partnering with industry, such as rope manufacturers, could help advance it to production mode.With climate change spurring the building industry to grapple with its high carbon footprint, reducing the use of heavily polluting materials like steel will become increasingly important. Tsamis says hemp rebar’s wide applicability makes it the kind of natural material the industry could adopt to cut down its massive impact. “It will demand a high volume of production, so we think it’s going to force some of the supply chain things to fall into place,” he says.