- | 9:00 am

How to create a beautiful home in the age of Instagram

A new book by the cofounders of ‘Sight Unseen’ dispels the myth of the picture-perfect home.

Spend enough time on social media and everything you see will start to blend into a blurry scroll of sameness. The same golden yellow sofas; the same East Fork mugs; the same, smooth millennial aesthetic. Instagram has flattened our idea of what makes a beautiful home—but there’s a world outside the online bubble, and it is filled with singular (and sometimes strange) objects.

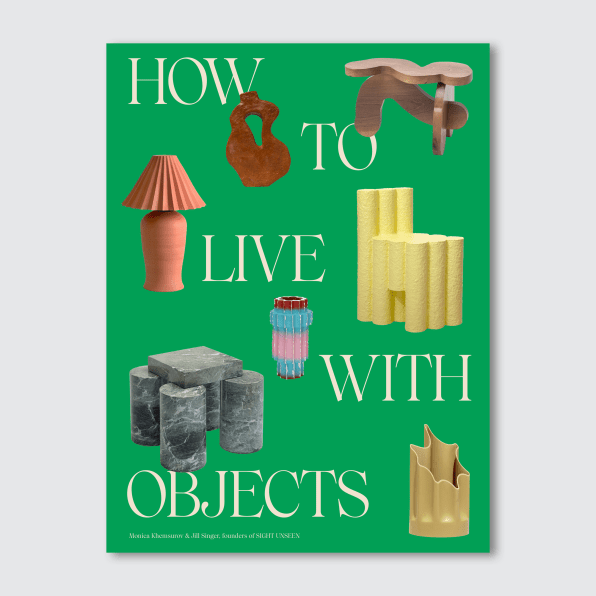

A new book titled How to Live with Objects: A Guide to More Meaningful Interiors argues that what defines our homes isn’t the picture-perfect interiors that social media and shelter magazines have long portrayed, but the design objects we choose to surround ourselves with—whether they are vintage, contemporary, handmade, or purely sentimental (which happen to be the four organizational categories of the book). The book makes the case that you don’t have to be an interior designer, or even a collector, to know how to source and live with objects. All you need is the ability to tap into your own personality and learn to translate it through objects. In other words, if you want to create a home that looks like you and no one else, then you should probably get off Instagram.

Monica Khemsurov and Jill Singer [Photo: courtesy Clarkson Potter/Random House]

How to Live with Objects is the brainchild of Monica Khemsurov and Jill Singer, the cofounders of the influential online magazine Sight Unseen. The book features more than 150 objects that run the gamut from a vintage painted-tile table (date unknown) to an odd wooden nail polish storage box made by the father of the owner when she was seven years old.

True to its title, the book reads like an approachable manual with shopping tips on where to source contemporary objects (design stores, galleries, showrooms, and design-school sales are featured among others), or how to snag vintage objects (go to flea markets early in the day, visit antiques malls multiple times to learn an object’s turnover rate). It’s a useful, illustrated guide for all the Marie Kondo challengers who find joy in amassing beautiful objects—but most of all, it’s a welcome reminder that there are as many definitions of “beautiful” as there are humans on this planet.

This idea flies in the face of the homogenous version of beauty found on platforms like Instagram and Pinterest, which have perpetuated so many of the interior trends we’ve seen in recent years. By default, social media only allows us to see what other people are posting about, and as a result, trends like “foam mirrors,” “starburst mirrors,” or Ettore Sottsass’ Instagram-famous Ultrafragola mirror (why is it always mirrors?) seem to suddenly show up in everyone’s homes.

For Khemsurov, social media may have sped up the homogenization of design, but it’s only amplified a phenomenon that already existed in various corners of the design world, from blanding to the pervasive nature of Helvetica. “Instagram has become an echo chamber in many ways, but the echo chamber is a larger problem,” she says. “It’s why we have things like Forever 21.”

The issue isn’t confined to new trends or fast furniture, though. Even objects sourced at a flea market or a parent’s attic or directly from a designer’s studio find their way online where others can use them as a source of design inspiration. “It’s a funny circular thing,” says Singer.

If you’re decorating a home and you’re online, there’s no way to fully get off the track of force-fed #designinspo. But maybe that’s not the worst thing. At the end of the day, both Khemsurov and Singer see Instagram as an educational tool that can help people discover new designers and makers and figure out what they like and dislike. “You can access this new information and have this learning experience no matter where you are,” says Singer. Just don’t make it your only learning experience.