- | 8:00 am

Humans have passports—buildings should, too

Architects are exploring how a “material passport” can encourage recycling at the building scale.

Our identity documents—passports, driver’s license, social security cards, for instance—convey essential information about who we are. It gives us access to basic rights like social security, healthcare, and the right to vote, and it allows us to move freely across borders. But a growing group of architects believe that humans aren’t the only ones who need an ID— buildings need one, too.

This concept, known as “material passports,” ensures when a building reaches the end of its lifespan, architects can refer to a building’s ID to understand the materials and components it’s made of, and reuse them instead of mining for new ones. Though it’s still a nascent idea in the architecture field, the big idea underpinning material passports is applicable to anyone who makes physical objects, be it a skyscraper or a dress: Namely, that every material is a resource, and that resources should be reused wherever possible.

Material passports are currently being explored in an exhibition on the circular economy in London. Developed by the Royal Institute of British Architects, Long Life, Low Energy: Designing for a Circular Economy explores various tools that architects can use to reduce the embodied carbon footprint of their buildings, including demountable structures, adaptive reuse, and urban mining. One of those tools is the material passport, which reframes buildings as material banks. “We chose to highlight material passports because they offer a significant opportunity to increase architectural reuse,” says Pete Collard, the exhibition’s curator.

Reused materials carry a lot of potential, but we simply don’t have enough data to do it consistently. This is where the material passport comes into play. Think of it as a detailed inventory or database that lists every component that comprises a building. For example, if your office building had a passport, you would know how many tons of steel went into building it, the kind of tiles your ceiling is made of, how many windows there are, including their size and if they’re single, double or triple-glazed. Armed with this array of information, an architect coming on-site to do an office renovation, or even to demolish a building, could figure out what materials can and can’t be claimed, reuse what they can, and save the rest for someone else.

Acquiring and logging all of this information is no small task, but for an industry like architecture and construction, which is responsible for nearly 40% of global CO2 emissions, it’s a crucial step in the right direction. “We cannot keep building the way we have been; we don’t have enough material, and the planet cannot cope with the carbon emissions,” says Rachel Hoolahan, an architect and sustainability coordinator at the London architecture firm Orms who’s been researching material passports for the past three years.

Hoolahan says a building moratorium would be the most effective way to slow down the impact of construction on climate change, but she acknowledges it’s neither possible nor reasonable. “We have to find way of continuing to develop buildings without putting so much carbon in atmosphere,” she says. “The only way we can meet that demand is by reusing materials we’ve already got, but at the moment there’s no practical, cost-effective way of doing this.”

Hoolahan initially faced this conundrum in 2019, when Orms was asked to convert three townhouses in central London into offices. After careful consideration, the architects concluded that the buildings, whose floors didn’t align, had to be demolished and rebuilt, but they wanted to reuse as many components from the old buildings as possible. To do that effectively, they needed an inventory of everything in the building, which simply didn’t exist. In the end, budgets changed and those buildings never ended up coming down, but the project became the basis of an ongoing research on how to accelerate material reuse at scale.

Dutch architect Thomas Rau originally proposed the idea of material passports in a book called Material Matters, which he cowrote with his partner Sabine Oberhuber (an English version is coming out in December 2022.) Rau abides by the philosophy that “waste is a material without an identity.”

In 2017, Rau cofounded Madaster, a commercial web platform that generates material passports based on a highly detailed 3D modeling software known as a BIM model. To date, the platform, which Hoolahan describes as a “text-based BIM model,” is only available in a handful of countries across Europe, including the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland, but according to Hoolahan, the concept hasn’t reached its full potential because it can only be used when designing new buildings, instead of retrofitting existing ones (a log for for existing buildings simply doesn’t exist).

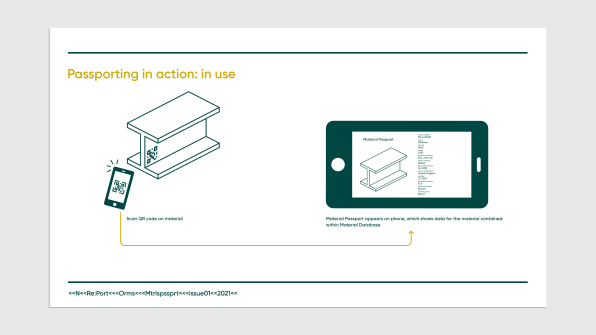

As a result, Orms decided to design its own version of a material passport. The new approach relies on a simple template that is free and available to anyone who is interested in giving it a go. Hoolahan envisions that a material passport can be created anytime work is being done on an existing building. During an office renovation, for example, every building component would be tagged with a physical sticker with a QR code on it, then linked to the corresponding record on an online database. Building surveyors could tag each component with relevant information. Architects could use the resulting inventory to inform their new design, and contractors could strip out the building with intent, moving salvageable parts to a storage facility until they can be reused.

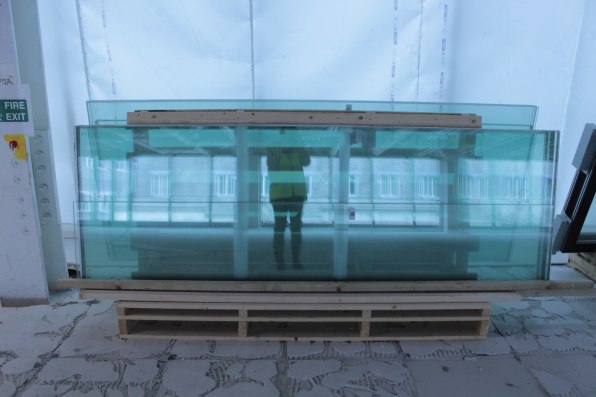

For now, it’s a time-consuming process that takes a village to implement. As a practice, material passports will likely grow slowly and organically as more architects and builders decide to embrace it. Hoolahan says eventually cataloging components will become easier (potentially with the help of an AI-powered surveying robot), but for the time being, architects can start small. Her number main advice: “pick one thing,” log all the information you can get, and try to reuse it in your next project. On a recent office renovation project, for example, the architects focused on ceilings and glass partitions. On another, they chose sinks.

To be sure, material passports are very much a work in progress, but the idea is gaining adoption across the building industry. Every quarter, Hoolahan convenes about 60 professionals who are working on the idea in some form, from architects to engineers, clients, quantity surveyors, and local authorities across Europe and the U.S. “Some are doing research, others are trialing and integrating [material passports] in their processes,” she says.

The results may not be visible for another decade, but if material passports are implemented at scale, they could help reverse engineer how we build in the first place, with a focus on recyclable materials and demountable buildings that don’t rely on irreversible construction techniques like mortar, or adhesives. “We’re holding people accountable for what happens when the building is done, so it’s about moving towards a circular economy,” says Hoolahan. “What do you do if all the landfills are closed? How do you work with what you’ve got?”