- | 7:00 am

Inside Lego’s secretive creative process that brings its best sets to life

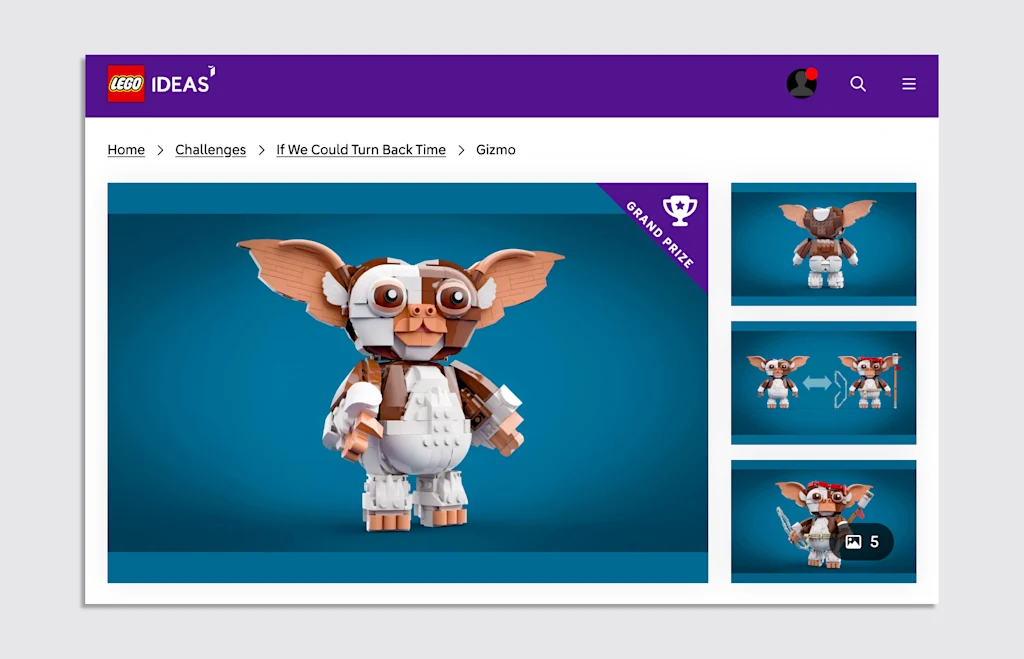

The Lego Ideas team, including its senior model designer, tells Fast Company how they turned ‘Gremlins’ icon Gizmo into a 1,125-piece set.

Fuma Terai is not a Lego designer.

Based in Japan, he is far away from Billund, the small Danish town where all the company’s official design work happens. And yet, Terai is responsible for one of Lego’s best sets of the year: Gizmo, the iconic creature from Joe Dante’s 1984 classic Gremlins.

In 2024, Terai submitted an adorable Mogwai as part of ‘80s design challenge from Lego Ideas, the company’s crowdsourcing community platform that turns fan ideas into real sets. More than a year later, his idea is now selling for $110 on Lego’s website.

Building a Lego set is an exhaustive process that marries creativity and technical precision. Before fans ever see a finished Lego product on shelves, its creation demanded a special negotiation between structural strength and playability, realism and abstraction. Lego designers have always needed to resolve impossible-seeming tensions to bring a set to life, and the creation of Gizmo, with his expressive features and fur, forced this process to its limits.

Chris McVeigh, Lego senior model designer, says creating Gizmo—like many other Lego sets—requires playing geometric tricks on the builder’s mind.

“There’s a lot of nuance to the shaping,” McVeigh says. “How can I round this corner in just the right way? How can I fill it in? How can I fill this in and make it look organic? Where is the abstraction?”

10,000 votes and counting

Gizmo, codenamed “Project Midnight” internally, was born from Lego’s Ideas platform, which crowdsources ideas for new sets from Lego’s biggest fans, as part of its 80s challenge. After Terai uploaded his design, it quickly garnered more than 10,000 votes—a number that automatically triggers Lego’s internal review process.

Monica Pedersen, Lego Ideas’ marketing director, says the first step is for Lego’s team to check for feasibility: can this physically be built? Are there intellectual property conflicts? Then there is a review of the submitting designer—is the fan “a good person” who can represent the Lego brand? After those questions are answered regional sales teams and retail experts evaluate commercial viability across different markets.

“We basically screen for design feasibility. Can it be built in real life? Are there restrictions that we cannot adhere to?” Pedersen says. Out of 177 product ideas that hit 10,000 votes last year, only five survived this winnowing process.

The redesign challenge

Most of the time, Lego designers take a fan’s creation and rework it from scratch. “One of the things that we decided on fairly early was that we wanted a little bit more nuance to the shaping than what we could see in the fan model,” McVeigh says.

McVeigh’s process began with what he calls “reference image work”—measuring proportions carefully against the original Gizmo puppet, determining scale through draw-overs, and identifying the key element that would define everything else. To do that, he needs to draw it.

“Part of my process is to do drawing. This is something that goes back to my art teacher in high school, who always said that you don’t really understand something until you have drawn it,” he tells me. With Gizmo, he only did a couple of sketches, to make sure that he got the scale right.

The eyes became the project design’s North Star for two reasons. First, he needed to get them right to match the character’s warmth and personality; Gizmo’s eyes are what defines him as a charming living creature. This included getting the eyeball’s size and look right but also his eyelids.

“It was very important to the aesthetic of this model to have these eyelids positioned in a way that they were over the eye,” McVeigh says. They could have “painted” the eyelids on a semi-spheric Lego piece that would act as his entire eye but they wanted to add a bit more dimension.

The eye design set a blueprint for everything else: “The key element was really the eye size and the size of the model and everything else just was tied to that,” he explains. “How the eyes would work was determined very early on with some brick-built mock-ups.”

The completed Gizmo uses 1,125 bricks and measures over 8 inches high, 10.5 inches wide, and 3.5 inches deep in standing pose—significantly larger than Terai’s original concept. “The size of the build has increased since I submitted my design on Lego Ideas,” Terai tells me with satisfaction.

The art of organic abstraction

For McVeigh, the relative similarity between his first physical prototype and the final product reflects successful upfront digital work. “The first built prototype I made doesn’t look that different from the final model,” he says. But beneath that surface consistency lay months of refinement—structural improvements, articulation engineering, and the careful balance between organic suggestion and geometric reality.

McVeigh had to find ways to suggest flowing hair and conjure the little Mogwai’s button nose. His job was to solve the three-dimensional problem of organic shapes with bricks. He knows that the magic happens the moment a person’s brain translates a cluster of simple plastic forms into the illusion of fur, flesh, or fabric.

Working digitally in Lego’s internal design tool, McVeigh started with a wireframe—shoulder points, pelvic points, basic proportions—before tackling the model’s greatest challenge: making plastic bricks that suggest organic fur and flesh.

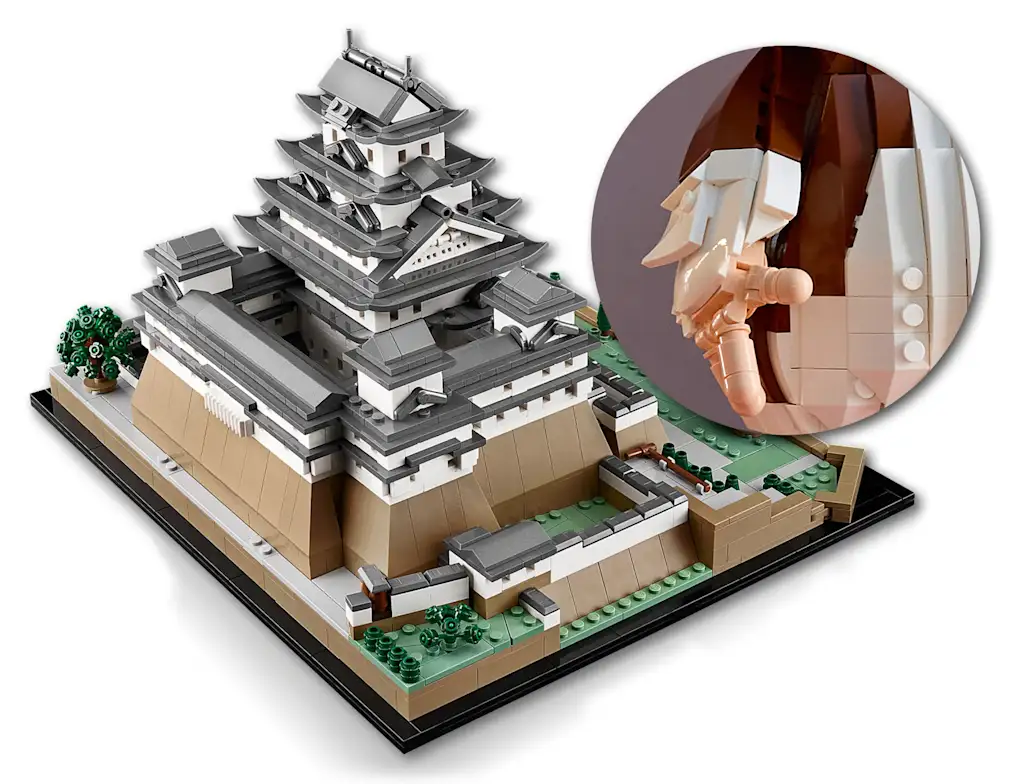

“One of the interesting challenges when you’re doing creatures is to give a sense of volume of hair when you are using Lego bricks,” McVeigh says. His solution relied on a specific element: a small 2×2 plate with an upturned corner that he had originally developed for Himeji Castle‘s roof edges, a Lego Architecture set released in 2023. “I decided to use that to give the effect of wispy hair flowing off the model,” he recalls. “I wanted to make sure that I use that in several places in the model so that the aesthetic was felt throughout.”

This approach exemplifies what McVeigh calls “abstraction”—the crucial decision of “where the model is going to be abstracted, where I know I can’t match something perfectly. And honestly, I think that’s part of what makes the product Lego-like, just that abstraction.”

The most challenging abstraction proved to be Gizmo’s nose. McVeigh started with large, flat designs, but they weren’t feeling quite right. McVeigh made the final change after a colleague’s gentle push: “Is there something you could do about the nose?”

He started experimenting with half-circle and full-circle plates, the flat rounded plates with 1 x 2 or 2 x 2 “Lego studs,” the little round protuberances sporting the Lego logo that make pieces stick together. They were hard to put in the model and required a significant redesign, but he really wanted to use them because of how they could capture the impression of nostrils, he tells me.

The final nose solution demonstrates the psychological cleverness underlying Lego design. The 2×2 round plate, with its subtle cutouts on its edge, “really sells the idea that it’s a nose” by fooling the brain into seeing nostrils where none exist. “It’s one of the exciting things about Lego,” McVeigh says. The brain fills the blanks.

The final model has two poses: standing and sitting. Players will have to choose which pose in advance, however, as Gizmo won’t move on its own. This is sometimes implemented in Lego builds with what McVeigh calls a “branch build” in the instructions: “At some point during the building instructions you will be asked to choose between OK, do you want to build Gizmo standing up or would you like to build him sitting down?” The model is not static, however. It features a rotating head, posable ears, articulated hands and arms, and leg rotation.

From a fan’s mind to store shelves

Throughout the design process, Terai remained involved as what Pedersen calls an “honorary Lego Ideas design member.” McVeigh says that every time they showed Terai the progress that they had made, “he would just light up—he was just grinning ear to ear.”

For McVeigh, capturing Gizmo’s soul in brick form is a perfect example of the prototypical Lego abstraction process. For Terai, it was a lesson in bringing an idea to life.

“Through working with the design team, I was able to see and understand how a product is created from start to finish,” Terai says. “I saw how they create a product. I have dreamed of designing Lego since I was a child, so it was a wonderful experience to be a part of.”