- | 8:58 am

Instagram is training AI on your data. It’s nearly impossible to opt out

Creators are training Instagram’s AI against their will, because Meta is using deceptive UX to keep them doing it.

Meta has started to mine Instagram images and videos to train its artificial intelligence models on the social media platform’s content. There is nothing you can do about it unless you live in the European Union. And even then, I found, opting out is unnecessarily difficult.

Just when you think that Meta had already committed every imaginable wrongdoing, all the way down to (allegedly) contributing to a genocide, the company has pulled more garbage out of its clown car’s trunk. By mining user creations for its own AI, Meta is effectively killing Instagram’s spirit while flipping the ultimate finger to all Instagrammers—especially those who joined the social network back when it was an independent playground for creativity and self-expression.

Instagram started as a way to share images so they looked as good as possible: Kevin Systrom created the app for iPhone in 2010 after a trip to Mexico, when his girlfriend didn’t want to share her photos online, arguing that they didn’t look nice enough. The app included screen-friendly cropping and some cool filters to make images look beautiful. And the feed’s visual simplicity made it an instant magnet for creative people, photographers, and artists worldwide. Regular people loved it too. Five years later, it had beaten Twitter in popularity, amassing 400 million users. Everyone, from indie creators to luxury fashion brands, wanted to be in. Now they’ll have a hard-to-impossible time opting out.

It’s no wonder that Reddit is up in arms after users learned that only EU residents can opt out of this abuse (and no, you can’t trick Meta into thinking you live in Paris with VPN—we tried). However, even Europeans such as myself will find the task difficult. Technically, European content is protected by privacy laws, and users living in that part of the world can opt out. However, Meta is employing several instances of deceptive design to dissuade that behavior.

HOW META MAKES IT HARD TO OPT OUT

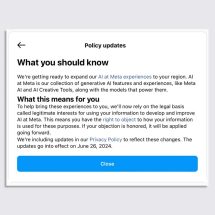

Consider the message that you have to access through your notifications section in Instagram (remember, it will appear only in the EU):

First notice the giant, blue “close” button in comparison to the almost invisible link on the words “right to object.”

Screenshot: courtesy of the author

“To help bring these experiences to you, we’ll now rely on the legal basis called legitimate interests for using your information to develop and improve Al at Meta. This means you have the right to object to how your information is used for these purposes. If your objection is honored, it will be applied going forward.”

What does “legal basis called legitimate interests” mean exactly? It’s a legal phrase that has nothing to do with a user’s decision here. Under EU privacy laws—called General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)—you have the right to opt out from Meta using your content. It’s that simple. This entire paragraph seems designed to make your head spin and hide that inline link that is already hard to see, making it so tempting to tap that big, blue “close” button instead.

Then notice the discouraging phrase “If your objection is honored.” That phrasing implies that Meta has a say in the matter as arbiter. The fact is that, no matter what, Meta has to honor such an objection from its users, according to EU law.

The discouragement continues when you click on the “right to object” inline link. This will take you to the opt-out form you can see below, which is again full of confusing text. Meta requires you to indicate your country of residence and type in your email address (this is an extra step of hassle that could have been avoided by just giving you the option to opt out within Instagram). Below that there are two text boxes. One requires you to explain why you don’t want Meta to use your content for AI mining, even though you should be able to opt out without any explanation under EU law. A second box allows you to provide “additional information that could help us review your objection,” further increasing the impression that this needs to be a bureaucratic process while, in fact, it should be automatic.

Screenshot: courtesy of the author

But the fun doesn’t stop there: The web page then required me to provide an authentication code sent to my email address (again, completely avoidable because I was logged into Instagram already) as if I were doing some bank transfer. Then, I had to complete an “Are you a robot?” challenge—a process I failed a dozen times before I finally gave up. (When I tried the next day, luckily, it worked.)

Consider how simple an alternative to this sketchy UX could be: a plain-English dialog box with the question “Would you like Meta to use your content for its AI model training?” with two buttons: YES or NO. That approach would have been painless and automatic. Of course, those are two qualities you don’t want when you’re trying to stop users from opting out.

When we reached out to Meta to inquire about these practices, the company reinforced that it was working in concordance with local laws. When asked if Meta had a comment for the creative community, who might view this AI training as a betrayal, a company spokesperson claimed that this was an inclusive rather than exploitative process, noting, “These features and experiences need to be trained on information that reflects the diverse cultures and languages of the European communities who will use them.”